Ethics Week 2

Read: Chapter 4, sections 1-3

4.1: intro

4.2: law, major cases

4.3: DRM, DMCA, arguments about copying

Normative ethics v descriptive ethics

Deontology v consequentialism

Relativism

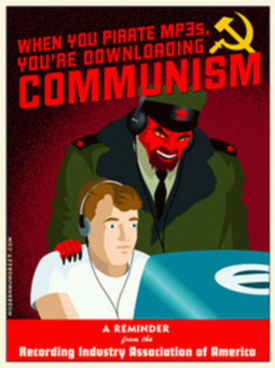

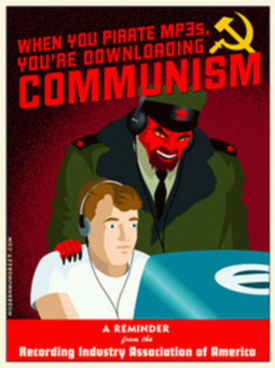

Application of this to music and movie file sharing.

Copyright law

Michael Eisner's June 2000 statement to Congress (edited, from Halbert & Ingulli 2004). See also below.

Who is copyright for?

Last week we reached the following question: who are music copyrights for? Here are the options:

- Musicians have a fundamental right to profit from their work

and creativity, and copyrights enable this right. Music copyrights are

about protecting a basic form of ownership to which musicians are

entitled.

- Music copyrights are there simply as a pragmatic gesture to

encourage musicians, so there will continue to be music for all of us

to enjoy. Music copyrights are about our future self-interest.

Despite the apparently clear distinction between fundamental duty and pragmatism here, it can be hard to tell.

It might help to think of how we would feel if some relatively minor

component of music copyright -- sheet-music sales, for example, or the

playing of prerecorded music at non-profit events -- were to be deleted

from copyright coverage. Such an action would surely not endanger the

music industry as a whole, so if we object, it is more likely that we

feel musicians are entitled to the fruits of their labor.

DEscriptive ethics: what do people actually do

compare sociology, etc

Normative ethics, or PREscriptive ethics: what should we do? (sometimes the phrase PROscriptive ethics is used to describe what we should not do).

-- "if seven million people are stealing, they aren't stealing"

-- is it ok to download music?

There is also the issue of what we should hold wrong in others. At the

severest level, this leads to some actions being illegal. At a more

moderate level, there are many actions that we find unacceptable in

others, but our response is limited to publicizing the action or

ostracism.

The literature on ethics is filled with what are sometimes called "ethical paradoxes":

The Trolley Problem (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trolley_problem)

A trolley

is running out of control down a track. In its path are 5 people who

have been tied to the track. Fortunately, you can flip a switch, which

will lead the trolley down a different track to safety. Unfortunately,

there is a single person tied to that track. Should you flip the switch?

The Cave Problem

A large person is stuck in the mouth of

a cave. His five smaller companions are behind him, inside the cave.

The tide is coming in, and will shortly drown them all. The stuck

person could be removed if he were killed.

Some more (many superficial) examples can be found at http://www.quose.com.

The Trolley and Cave problems seem grimly remote from ordinary experience.

File-sharing, however, is not, hence makes a more everyday example.

Ethical theory

(often inseparable from Political & Justice theories)

Deontological ethics: (deon = duty)

Based on the enumeration of fundamental, universal principles.

Immanuel Kant [1724-1804]

Kant's categorical imperative:

all our principles should be Universal;

that is, if it's ok for us, personally, then it must be ok for

everyone. Also, whatever it is must be ok in all contexts, not just

selecively (that is, rules apply universally to people and universally

to acts). We are to choose ethical principles based on this idea of

universality.

This is

close to, but not the same as, the Golden Rule: "do unto others as you would have them do unto you [Matthew 7:12]"

[NB: is the Bible in the public domain?]; outcome might be the same,

but the Golden Rule doesn't have the explicit notion of universality.

Kant also said that people should not be treated as means to other

goals; they should be the "endpoints" of moral action. Kant also

famously claimed the two principles (universal and non-means) were THE

SAME.

Kant is often regarded as a Moral Absolutist, a stronger position than deontology necessarily requires.

WD Ross [1877-1971]:

more modern deontologist

consequentialism is wrong; Ross identified "seven duties" we have to each other:

- fidelity [not lying, keeping promises]

- reparation [making up for accidental harm to others]

- gratitude

- non-injury [do no intentional harm others; includes harming their happiness]

- justice [or prevention of harm by others?];

- beneficence [do good to others. How much good?]

- self-improvement [perhaps "taking care of oneself"]

Is this list complete?

But perhaps the biggest problem for deontologists is what do we do when rules conflict?

Abortion: duty to mother v duty to fetus

This would be the issue facing someone trying to use

ethics to decide whether to support or oppose a law banning abortion.

Copyright: duty to copyright-holder v duty to society

But the rights of the copyright holder and the rights of society are largely not in conflict!

What about one's personal duty, when faced with the choice of downloading music?

Consequentialist ethics

Jeremy Bentham 1749-1832 & John Stuart Mill [1806-1873]:

Consequentialism

(Utilitarianism): the good is that which brings

benefit to the people (greatest good for greatest number). This is also

sometimes referred to as the "greatest-happiness principle". Another

way to look at it is that it calls us to weigh benefits against harms.

Bentham's original formulation called for maximizing "pleasure" and

minimizing "pain", for society as a whole.

[Bentham apparently believed it was not ok to HARM a minority to benefit the majority, though this has always been an issue

with Consequentialism. One approach to this problem is to weigh HARM

much more heavily than BENEFIT, but what if the HARM is just to one

person? More on that below.]

Bentham developed an entire legal code based on his theories.

Bentham's version had a problem with justice: is it ok to take the

factory from the owner? (That scenario remains a central obstacle for

consequentialism.)

Mill wrote a book, Utilitarianism.

He was much less flat-consequentialist than Bentham. Bentham thought

all forms of pleasure were comparable; Mill felt some were "better"

than others. Mill also recast the idea as maximizing happiness rather than "pleasure".

Social Contract; Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau

We make rules to move from the State of Nature to Civilization. That

is, we agree to social/ethical rules due to their CONSEQUENCES, because

we WANT those consequences.

Law and the Social Contract

Ethics and the Social Contract: Ethics are in our long-term self-interest? (Under the social contract)

The idea is that if we lie, or cheat or steal, then eventually our reputation will precede us, and we will end up losing.

Problem: this theory works better for some scenarios than others.

John Rawls [1921-2002]: In

negotiating the Social Contract, everyone must be placed behind the

VEIL OF IGNORANCE, not knowing whether they would be strong or weak,

rich or poor, healthy or sick. (This is often interpreted as "decide on

society before you were born") They would then choose what world they

wanted to live in. What ethical & legal rules do you want in place?

[Usually thought of as a theory of justice, not ethics, but these are

actually pretty closely related.]

How do you think Rawls would vote on health-care reform?

How do you think Rawls would choose between capitalism and socialism?

More on consequentialism

zero-sum consequentialism: The

idea is that, notionally, we score everyone's benefit or damage

numerically, and add them all up. The foremost problem with this

approach is that it accepts solutions in which one person suffers

greatly, but which produces a modest rise in the fortunes of everyone

else. Ursula LeGuin wrote a short science-fiction story on this theme:

"the ones who walk away from Omelas." This is also a theme of William

James in his essay The Moral Philosopher and the Moral Life. Look up "omelas" on Wikipedia to find James' quote and a link to the full essay; the quote itself follows.

Or if the hypothesis were offered us of

a world in which Messrs. Fourier's and Bellamy's and Morris's utopias

should all be outdone, and millions kept permanently happy on the one

simple condition that a certain lost soul on the far-off edge of things

should lead a life of lonely torture, what except a specifical and

independent sort of emotion can it be which would make us immediately

feel, even though an impulse arose within us to clutch at the happiness

so offered, how hideous a thing would be its enjoyment when

deliberately accepted as the fruit of such a bargain? - William James

min/max consequentialism: goal is to choose actions that minimize the harm to those affected most

(to minimize the worst case, ie to minimize the maximum). Example:

taxes; everyone pays a share and social progress is thereby funded.

disinterested-person consequentialism:

To decide for or against a rule using consequentialist reasoning, you

must be a disinterested party: you must NOT stand to gain personally in

any significant way. How does this shift our perspective in the

copyright debate?

act consequentialism:

consider consequences of each individual act separately. Some lies may thus be

permissible while others may not be. The same would apply to music

downloading: music from some bands might be fair game. But how do you

decide?

rule consequentialism: use

consequences of hypothetical actions to formulate broad rules. For

example, we ask if we are better off tolerating lying or not; we might

then arrive at the broad conclusion that lying is not helpful to

society, and we would apply it in every case. Rule consequentialism

generally fares better under critical analysis than act

consequentialism, but there is a difficulty with how broadly the rules

should be interpreted. Is your rule that "lying is always wrong"? Or is

it that "lying when someone will be hurt is wrong"? Or "lying is wrong

even if no one is hurt, if by lying I gain something I would not

otherwise receive"??

"the ends justify the means"

This position is based on the consequentialist argument that sometimes

it's ok to lie (the means), because in those special cases (eg not

hurting people's feelings, protecting the innocent) the ends are

clearly an overall good. However, in general consequentialism requires

us to take into consideration the full consequences of the means (as well as the ends), in which case harsh or inappropriate means might be discarded as unacceptable.

Famous examples:

Compare justifications of lying

Utilitarian: may be ok in some cases

Act Utilitarianism: very case-by-case:

Lying to Joe during the job interview: WRONG

Lying to Bob about our having borrowed his car: maybe

Lying to Mary about where we were last saturday: sure!

Rule Utilitarianism: by category

"Lying to

friends" may be a category that is always wrong.

Or should the category be "Lying to Anyone"?

Deontological theories: Lying Is Wrong. Always. Even to save refugees from the Nazis.

Kant: no moral issue should EVER be decided on a case-by-case basis

Compare approaches to criminal punishment

Utilitarian: pragmatic; jail is for rehabilitation

Deontological: jail is for punishment

Which approach do we take in current societal discourse?

"Natural right to property" is mostly a deontological notion: Locke's

idea that people had a natural right to the product of their work did

not have societal economic benefits as its justification. However, it is rather easy to defend property rights with a consequentialist argument.

Constitutional language re copyright is CLEARLY focused on overall benefit to society (utilitarian)

Most laws are largely utilitarian. Note, though, that some aspects

of free speech / freedom of religion make these out to be "fundamental

rights" in a deontological sense.

Some alternatives and special cases

Aretaic Ethics: from greek "Arete", virtue or excellence

Important thing is not duties or consequences but one's character. If

you have the right character, you will be led to ethical action

naturally. [Not mentioned in Baase]

Rights Theory

We all have certain inalienable rights, and the

goal of ethics should

be to preserve these. Note that this is different from duties. Locke's

"natural rights" comes from this perspective. Rights-theory ethics

says, basically, that ethics is about respecting other peoples rights.

Do other people have a right not to be misled?

Liberties and claim rights: (Baase)

Liberties

(sometimes called negative rights) are rights "to act without

interference"; others SHOULD NOT interfere with these. Examples:

- right to life

- right to (physical) property

- freedom of speech

- right to hire your own attorney

- right to play the music we buy???

Claim rights (positive rights): rest of us have to take measures to ENABLE your right.

- right to be provided with an attorney (compare liberty version of this)

- right to an education

- right to have our copyrighted content protected by the government

Sometimes these are in conflict. Claim rights put an obligation on

the rest of us to GIVE UP something, likely something to which we have

a liberty-right.

Rights-theory ethics is probably more commonly about liberties than

claim rights, but both are involved. Note that with liberties, our ethical obligations are to preserve the liberty-rights of others.

Basis for Property rights

John Locke [Baase, p 33]: Is copyright a PROPERTY right?

"Natural"

rights: special case of liberties (negative rights), like life &

liberty. These are fundamental obligations we have to one another.

"Utilitarian" rights: rights that we grant each other for improved social function; NOT necessarily the same as claim rights

The Constitution places IP in the latter category.

Religion

How does religion figure into ethics?

There has been a surprising amount of theological debate about whether even God is subject to moral law.

Another theological issue is whether having religious rules takes away our "right" or obligation to make moral decisions.

10 commandments: very deontological. They are fundamental duties, and they are expressed as universals.

613 Mitzvot of the Torah: some of these are less universal (though that is clearly not their point).

Golden Rule [Matthew 7:12]:

"do unto others as you would have them do unto you"

See also "though shalt love thy neighbor as thyself" [Leviticus 19:18]

This is closer to consequentialist than to deontological, but still

different. It does identify a duty in how we treat others, but any

actual details of how we are to carry out this duty are grounded in

pragmatism: how we would feel if our action were to be applied to us.

Some people call the golden rule "reciprocity ethics". However,

arguably the rule's real meaning is as a way of understanding how to

treat others, even if they do not reciprocate.

The Golden Rule is closely associated with Jesus, but the Jewish

scholar Hillel the Elder, supposedly born 110 BC but also supposedly

overlapping with Jesus, gave the

following as the core teaching of the Torah:

That which is hateful to you, do not do to your fellow.

Hillel probably said this sometime between 30 BC and 10 AD; a

similar formulation appears in the noncanonical biblical books Tobit

and Sirach. This is similar to the Golden Rule; however, note that Hillel's formulation is more like

"do not do unto

others what you would not have them do unto you"

This formulation is

sometimes referred to as the Silver Rule.

The prophet Muhammad also said something similar: Hurt no one so that no one may hurt you. [The Farewell Sermon, 632

AD].

However, some ethicists have felt that it is a clearer statement of our

moral obligation to one another, rooted in the underlying principle

that we should not harm others. The latter was clearly expressed by the time of ancient Athens (~500 BC).

Note that the Silver Rule really states "do no harm"; the part about "what you would not have them do unto you" is really about defining what harm is (that is, it's harmful if you think it would be harmful to you).

Similarly, the Golden Rule might be shortened to "do good", where good

is defined as what you would want done, but this analogy isn't quite as

exact.

The Golden Rule might be seen as requiring us to give actively to

others, beyond merely not harming them. It is not always interpreted

this way, though.

The underlying "reciprocity principle" of ethics has come up many times.

The Golden Rule has been widely criticized as not providing much of a way to find out whether others in fact want

to be treated the same way you want to be treated. However, if it is

applied primarily to the "big picture" issues of fairness and

consideration, these objections have less strength.

Professional ethics

Law: lawyers have a legal AND ethical responsibility to take their client's side!

This can mean some behavior that would be pretty dicey in other circumstances.

Corporations: have a legal AND ethical responsibility to look after shareholders' financial interests.

This is not to say that a lawyer or a corporation might not have other ethical obligations as well.

Wrong v Harm

Not everything that is harmful is wrong.

Example: business competition

Not everything that is wrong is harmful:

Hackers used to argue

that it was ok to break into a computer system as long as you did

no harm. While there are some differences of opinion on this, most

people who were broken into felt differently.

Law v Ethics (p 37)

Laws:

implement moral imperatives

implement, enforce, and fund rights

fund services

establish conventions (eg Uniform Commercial Code)

special interests

How do we decide what rules OTHERS should follow?

(Quite unrelated to how we decide what rules we ourselves follow.)

Ethical Relativism: it's up to

the individual [or culture]. "Moral values are relative to a particular

culture and cannot be judged outside of that culture" [LM Hinman, Ethics, Harcourt Brace 1994]. Hinman is speaking of "cultural ethical

relativism"; a related form is "individual ethical relativism",

sometimes called ethical subjectivism. That is, it's all up to you

personally.

Does ethical relativism help at all with deciding questions facing you?

See Baase, p 32, under Natural Rights:

One approach we might

follow is to let people (or cultures) make their own decisions. This

approach has less meaning in the context of deciding how we should act

personally. It is very attractive because (at first glance, at least), it is nonjudgmental, seems to promote tolerance, and seems to recognize that each of us arrive at our ethical positions via our own path.

Relativism has, however, some serious problems.

First, we often don't really believe this. Example:

murder/genocide; do we really mean that this is would be ok in Darfur

if the Sudanese culture accepts it? The Nazi culture (at least the

culture of higher party members) accepted genocide; do we really want

to stick with relativism here?

Second, the central claim of relativism is that it is wrong to criticize the ethical principles of others. This in itself is an absolute (non-relative) statement, and as such is self-contradictory!

The utilitarians and Kantians seem to suggest that part of an ethical theory is how it affects everyone; that is, it's not just up to you.

Some references in

Baase illustrating that "Intellectual Property" is indeed a special

case and not just an instance of physical property. For physical property, once we buy it there are no further strings.

p 199:

When we buy a movie on digital video disk (DVD), we are

buying one copy with the right to watch it but not to play it in a

public venue or charge a fee. [license/copyright strings attached]

p 200: five copyright rights [would these ever apply to physical property?]

- make copies

- produce derivative works (except parodies); includes translations

- distribution of copies

- performance in public

- display to the public

p 201 [is the future of the laws on physical property in doubt?]

Nicholas Negroponte: "Copyright law will disintegrate"

founder, MIT Media Lab

founder, One Laptop Per Child; goal: $100 laptop

Pamela Samuelson: "[no they won't]... balanced solutions will be found"

Cornell Law prof

writes Legally Speaking column in Comm. ACM

Suppose we do agree that songs are a form of property. Does that

automatically mean we agree on what theft is? A bit of thought makes it

clear that the answer is no: traditionally, the point of theft is that

it denies the owner the use of the item. Traditional notions of theft

just don't make sense here.

What about "unauthorized use"? That's a reasonable first approximation,

BUT it opens up a huge can of worms as to what constitutes

"authorization" and what constitutes "use".

Application of deontological/utilitarian analysis to music file-sharing

Music stakeholders (list from before (simplified)), with an indication as to how they might fare under file-sharing.

"signed" musicians

|

lose

|

"indie" musicians

|

gain

|

recording industry

|

lose big

|

stores & distributors

|

??

|

current fans

|

gain

|

future fans

|

lose

|

Utilitarian perspective:

probably uses tradeoffs as summarized in the table above.

(might or might not weight recording industry $$$ losses higher than others.)

Deontological perspective probably would NOT consider these tradeoffs.

END OF CLASS, week 2

Deontological perspective:

universal principles: respect for others, fairness, honesty

One approach: downloading is a form of theft.

Another approach: "we simply do not have ownership rights to information" (Stallman, later)

After all, we cannot own slaves either (in the US since 1865)

Kant, the Categorical Imperative, & file sharing:

do I really want file sharing to be ALWAYS ok?

Is free downloading a form of "using" other people? (Kant was against that)

Problem with strict ownership: social progress REALLY stalls. We'll

see this later with patents, but entertainment is also based on

incremental development, and one artist's response to others.

signed v indie musicians & all this

utilitarian: which scheme is better for which type?

deontological:

do we owe signed musicians the right to decide distribution?

do we owe indie musicians the right to an opportunity?

Could we have both??

Why would people buy CDs? Some answers from ~2002:

- consistent quality

- "an official, completed object. It's satisfying"

- concrete

- album notes, photos

- light & portable

Is there ANY way nowadays in which a CD is better than the download? (Of course, now you can buy from iTunes instead.)

What happens to the notion that there was some equilibrium

reached between file-sharing and CD sales based on CD's still having an advantage? Did Eisner start this

by agreeing that, as free music became more prevalent, it was

appropriate to cut prices on for-sale music?

John Rawls & justice / ethics

Imagine that you have NOT YET

BEEN BORN, and you do not yet know to what station in life you will be

born. How does this affect your ideas about music pricing?

Your perspective might be very different if you knew you were going

to be a songwriter, versus (just) an ordinary listener. However, you

might also argue that (a) you like music, and therefore (b) you want

musicians to be able to earn a living, because otherwise there won't be much music.

Per-track pricing at iTunes: how does THIS change the market model?

Fundamental conflict: evolution of technology v rights of creators

Is going back to the old way an option?

Napster

Napster was started June 1999. Content owners promptly sued, and Napster lost in federal district court in 2000. The Ninth

Circuit appeals court then agreed to hear the case. They granted an injunction allowing

Napster to continue operating until the case was decided, because they took

seriously Napster's arguments that Napster might have "substantial

non-infringing uses" and that Napster was only a kind of search engine while

the real copyright violators were the users. The Ninth Circuit eventually found that Napster

did indeed have Substantial Non-Infringing Uses, but they ruled against

Napster by January 2001. After some negotiating, Napster was ordered in March 2001 to remove infringing content,

which they technologically simply could not do, and so they shut down in July of that year.

Bottom line: Betamax videotaping precedent was rejected because,

although SNIUs existed for Napsster, Napster had actual knowledge of

specific infringing material and failed to act to block or remove it.

Also, Napster did profit from it.

However,

the court refused to issue an injunction for quite a while; it was

clear that the Betamax precedent was being taken very seriously.

Legality in Napster era: napster.com was a clearinghouse for who was

online, and what songs they held. Actual copying was between peers.

Did that make it ok?

Napster figured the RIAA would never bother with individual lawsuits against users.

Were they right?

Are such suits justified?

What evidence is needed for subpoena?

Note that signed and indie musicians fare VERY differently under the napster model!

Also note the long-term implications for "future fans"

IS napster like radio?

Napsterized business model for musicians:

make money giving live concerts, not selling CDs.

IS THIS REALISTIC? IS THIS FAIR? IS THIS JUST LIFE?

Is this a case of "harm" being unequal to "wrong"?

Question: is it ethical to cause harm?

What about economic harm?

RIAA Lawsuits

File-sharing software works by sharing your files too; advertising

your music folder(s) online when you join the service. Investigators

look for these, by participating in online file-sharing networks. They

record your IP address and the listed songs; they also generally

download a few of the songs.

Different software works different

ways. Kazaa shows a "share" folder. bittorrent shows your connection to

a torrent "tracker" site, but there's no notion of "shared files".

Step 1: The RIAA files a "John Doe" lawsuit against your ISP. They

issue a subpoena to your ISP, asking for your name, and, if relevant,

the MAC address of your computer. These subpoenas are almost always in

a group, asking for multiple customer names.

One legal criticism of RIAA lawsuits has been over joining together

of multiple individuals in one ISP lawsuit. Normally you can't do that

unless you believe the cases are related.

Prior to December 19, 2003, the RIAA didn't need to sue ISPs: it could subpoena ISP records without

a lawsuit, under a provision of the DMCA. But then a court ruled that

this DMCA provision did not apply to RIAA-type cases. [RIAA v Verizon]

The ISP usually complies, usually without contacting you. However, it

is possible for either the ISP or you (if the ISP contacts you) to file

in court to "quash" the subpoena. You do need a reason for that,

however. It *is* possible to file to quash without giving up your

identity, but you have to hire a lawyer.

Step 2: the RIAA now sends you a settlement letter, offering you a

chance to settle before the lawsuit is filed. The settlement offer is

usually something like $500-1000 per track. The RIAA may or may not

distinguish between tracks that showed up in your directory, and/or

tracks that they actually downloaded.

You can refuse to settle. However, in that case the RIAA will almost certainly go to Step 3.

Once the possibility of a lawsuit is raised, destroying evidence becomes both a civil and criminal offense.

Step 3: The RIAA files a lawsuit. They will ask for a forensic copy of

your hard drives (they may ask for the hard drives themselves, but

you're under no obligation to give them up). An independent forensic

examiner will copy the drive, and determine whether or not the songs

are there. (The MAC addrss from Step 1 plays a role here in determining

whether they've got the right computer; so does other identifying

information about KaZaa,etc.)

The cost of settlement goes up a little at this point.

Some defenses that have NOT helped:

- the ISP is your school, and releasing school records is illegal.

(releasing names is not illegal)

- you didn't know it was against the law.

Yes you did. Come on. But it doesn't matter.

- you already owned the tracks on CD.

See the Gonzalez case; www.eff.org/wp/riaa-v-people-years-later. Copyright

law allows you to make a backup copy of what you bought; there is no

provision for receiving your backup copy from someone else.

Some possibly valid defenses in court:

The problem with all these is that you don't want to be going to court,

and the RIAA does not have to consider these when settling.

It wasn't your computer.

Typically this is due to the ISP's

misidentification of you. Sometimes it's because someone jacked your

wi-fi. In this case the forensic examination of your computer will probably help.

Your roommate used your computer

Your problem here is proving that this is the case.

Your kids used your computer

There is a very limited legal doctrine of parental responsibility.

Originally, the RIAA did sue parents, or made them settlement offers.

More recently, after several losses, the RIAA has been suing the minors

themselves. This is a little tricky; the court must appoint an

attorney, often at the RIAA's expense. Also, in Capitol_v_Foster,

Deborah Foster eventually won $68,000 in legal fees from the RIAA.

Foster's daughter did the downloading. (The case was brought in 2004;

the RIAA dropped their suit a year later but Foster continued with her

countersuit. The judge eventually ordered the award for legal costs

without a full trial.)

You didn't actually download any songs

What the RIAA has, as

evidence, isn't evidence of downloading. All they

have is evidence that you "offered" songs for downloading. At this

point it might matter a great deal whether the RIAA actually tried

downloading anything from your computer. Jammie Thomas had her case go

to trial (the first RIAA case to reach a jury trial; Tenenbaum's July

2009 trial was the second) and she lost and was ordered to pay

$220,000. But Judge Michael Davis later rethought this issue, rejected

the "offered for distribution" theory, and ordered a new trial. Alas,

the new trial reached a judgement against Thomas of $1.9 million.

Tenenbaum case

Joel Tenenbaum was caught downloading files by the

RIAA, and was offered their past settlement offer, typically about

$5000. He chose to fight. He got Harvard Law professor Charles Nesson to take his case pro bono; Nesson also involved his law-school class. They put up a vigorous and spirited defense before Judge Nancy Gertner.

They lost.

When it came time to assess damages (July 31, 2009), the jury decided $22,500 per track was fair, for a total of $675,000. Oops.

Actually, a core part of Tenenbaum's defense, and the central part of

his appeal, is that the damages (and settlement offer) were

disproportionately high, and not tied to actual

damages. Normally, when you sue someone, all you can ask for is actual

damages. Actual retail cost of music tracks is about $1. Tenenbaum got

Tenenbaum's case was the second RIAA case to go to trial. Jammie

Thomas-Rasset was first; in her first case the verdict was $222,000.

Thomas-Rasset got a new trial; the second verdict was $1,920,000.

Moral: think hard about settling early.

Tenenbaum's music downloading appeared to be both intentional and egregious; he had actually been sharing some 800 songs. However, it was done when he was a student.

An interesting point about the case is how the judge dismissed the

fair-use claim based on the legal theory that fair use could not apply after

Apple opened its iTunes store; that is, once it became possible to buy

individual tracks, file-sharers lost any claim to fair use. That is,

the underlying justification for "fair use" was that mp3 tracks were

otherwise unavailable. Tenenbaum's appeal in part is about the idea

that until iTunes dropped DRM its music tracks were still not really

comparable to downloaded ones.

See http://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/news/2009/07/o-tenenbaum-riaa-wins-675000-or-22500-per-song.ars. and the links at the end to earlier articles.

It's really hard to generate much sympathy for the RIAA methods.

Consider, though, the theory that file sharing is a violation of their

copyrights, and that such individual lawsuits are the ONLYway to

proceed.

What's unfair about this process? What is fixable, within the constraints of the US legal system?

Some things to think about:

- statuary damages for infringement

- rules for defendants who cannot afford an attorney

- rules of evidence

RIAA-2

The RIAA has officially given up on filing lawsuits against infringers,

at least for now; they announced this policy in December 2008, just

after the Tenenbaum case (lawsuits still in the pipeline will

continue). The new policy is to work with ISPs to

- notify users of infringement for the first offense

- cut off their internet access (perhaps slowing it for a while, first)

See http://www.wired.com/epicenter/2008/12/riaa-says-it-pl.

Why would ISPs want to go along with this plan? Here are a few reasons:

- file-sharers are also huge bandwidth hogs. (Linux users are too,

but there aren't enough of us to matter. (How many times a day do you

rebuild your kernel?)) The

broadband business model basically gives every customer the ability to

download several dozen gigabytes a day, but the hope is that most

customers will actually download somewhere in the range of dozens of

megabytes a day. File-sharers who download movies pretty solidly put

themselves in the heavy-downloaders camp, tying up resources for

everyone.

- The ISP might get sued. The RIAA probably wouldn't win, but it would be an expensive hassle.

- It's the Right Thing To Do. Knowingly cooperating with copyright infringement is wrong.

- Eventually, the RIAA is likely to press for laws requiring ISPs to cooperate. Better get started now.