Privacy and Commercial and Social Interests

Readings

Baase Chapter 2.

Privacy from others

Internet Search Records

Webcam Spying

Pennsylvania School Laptops

Facebook

News Feeds

Advertising

Facial

Recognition at Facebook

Privacy Settings

Credit Bureaus and Credit-like Information

Facial Recognition

Tinder

Managing your privacy

Public Records

Theories

Workplace Email

Smyth v Pillsbury

Advertising

Location data

Target

RFID

SSNs

Price Discrimination

Google Buzz

Google Buzz was google's first attempt at a social-networking site, back in

~2009[?]. When it was first introduced, your top gmail/gchat contacts were

made public as "friends", even though the existence of your correspondence

may have been very private. For many, the issue isn't so much that yet

another social-networking site made a privacy-related goof, but that it was

Google, which has so much private

information already. Google has the entire email history for many people,

and the entire search history for many others. The Google Buzz incident can

be interpreted as an indication that, despite having so much personal

information, Google is sometimes "clueless" about privacy. At the very

least, Google used personal data without authorization.

For many people, though, the biggest issue isn't privacy per se, but the

fact that their "google profile" overnight became their buzz page, without

so much as notification.

See http://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/15/technology/internet/15google.html.

Or http://searchengineland.com/how-google-buzz-hijacks-your-google-profile-36693.

Google search data

Consider the following site (which is an advertisement for duckduckgo.com):

http://donttrack.us/

Some points:

- Every site you go to, no

matter how you found it, has your IP address (unless you attempt to hide

that); this is not new.

- When you click on a link to a site that appears in a google search,

the site gets your search term from google. You can also copy/paste the

site URL, which usually avoids this.

- third-party advertisers track you with cookies and whatever other data

(eg search data) they can obtain.

- While Google can sell your search data to others, they are under

considerable marketplace pressure not to. This does not, however, apply

to those third-party advertisers.

To be fair, Google famously resisted a US subpoena for a large sample of

"anonymized" search records, even before the AOL search leak (below) when it

became clear to everyone that these were a bad idea.

AOL search leak, 2006

Baase 4e pp 50-51 / 5e p 56: search-query data: Google case, AOL leak.

In August 2006, an AOL scientist released 20,000,000 queries from ~650,000

people. The data was supposedly "anonymized", and did not include IP

addresses, but MANY of the people involved could be individually identified,

because they:

- searched for their own name

- searched for their car, town, neighborhood, etc

Many people also searched for medical issues.

Wikipedia: "AOL_search_data_scandal"

Thelma Arnold was one of those whose searches were made public. The New

York Times tracked her down; she agreed to allow her name to be used. See

www.nytimes.com/2006/08/09/technology/09aol.html.

As of 2018 the actual data can still be found on the Internet.

See: www.techcrunch.com/2006/08/06/aol-proudly-releases-massive-amounts-of-user-search-data

What would make search data sufficiently anonymous?

Question: Is it ethical to use the actual

AOL data in research? What guidelines should be in place?

Are there other ways to get legitimate search data for sociological

research?

How much of your google-search history is stored on your computer? Where is

it?

What constitutes "consent" to a privacy policy?

Are these binding? (Probably yes, legally, though that is still being

debated)

Have we in any way consented to having our search data released?

Search records and computer forensics

In 2002, Justin Barber was found shot four times on a

beach in Florida. None of his injuries were serious. His wife April,

however, had been shot dead. Barber described the event as an attempted

robbery.

There were some other factors though:

- Barber had recently taken out a large life-insurance policy on his

wife

- Barber was having an affair

- Barber was heavily in debt

- April Barber's family was sure Justin did it

Police searched Barber's computer for evidence of past Google searches. They

apparently did not contact Google

directly. Barber had searched for information on gunshot wounds,

specifically to the chest, and under what circumstances they were less

serious. Barber was convicted.

More at:

http://news.cnet.com/8301-13578_3-10150669-38.html

Lee Harbert:

Harbert's vehicle struck and killed Gurdeep Kaur in 2005. Harbert fled the

scene. When arrested later, his defense was that he thought he had hit a

deer. But his on-computer searches were for

"auto glass reporting requirements to law enforcement"

"auto glass, Las Vegas" (the crime was in California)

"auto theft"

He also searched for information on the accident itself. Harbert too was

convicted.

more at http://news.cnet.com/8301-13578_3-10143275-38.html

Wendi Mae Davidson

Police found her husband's body in a pond at the ranch where Davidson

boarded her horse. Police found the ranch itself by attaching a GPS recorder

to her car. Davidson also used an online search engine to search for the

phrase "decomposition of a body in water".

More at http://news.cnet.com/Police-Blotter-Murderer-nabbed-via-tracking,-Web-search/2100-7348_3-6234678.html

Neil Entwistle

Entwistle's wife Rachel and daughter Lillian were found shot to death in

January 2006. Neil had departed for England. Besides the flight, there was

other physical evidence linking him to the murders. However, there was also

the Google searches:

A search of Entwistle's computer also

revealed that days before the murders, Entwistle looked at a website that

described "how to kill people" ....

More at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neil_Entwistle

Casey Anthony

On the last day that two-year-old Caylee Anthony was seen alive (in 2008),

someone in Casey Anthony's house googled for "fool-proof suffication" [sic],

using Firefox. This was the browser primarily used by Casey; most other

household members used Internet Explorer.

Casey was acquitted in the case of Caylee's death. The prosecutor was not

aware of the Firefox search history, due to a police error.

How do such cases relate to the AOL search-data leak, and Thelma Arnold?

While none of the AOL individuals was charged with anything, some of their

searches (particularly those related to violent pornography) are rather

disturbing.

Where is google-search-history stored on your computer? Is

it stored anywhere, anymore? Does this make you more interested in duckduckgo.com

(and donttrack.us)?

Webcam Spying

If you have a laptop with a webcam, someone might turn it on. If your laptop

has a microphone, that can be turned on too.

Tyler Clementi

On September 19, 2010, Rutgers University Tyler Clementi asked his roommate

Dharun Ravi to be out of the room for the evening. Clementi then invited a

male friend and they kissed. Ravi, meanwhile, turned on his webcam remotely

from a friend's room, watched the encounter, and streamed it live over the

internet.

Ravi told friends he would stream the video again on September 21, but

Clementi turned off Ravi's computer. That night Clementi filed an official

invasion-of-privacy complaint with Rutgers, and requested a single room. The

next day Clementi leapt to his death from the George Washington bridge. His

exact motives remain unclear; his family did know he was gay.

How much is this about invasion of privacy?

How much is this about harassment of homosexuals?

How much is this about bullying?

What about Erin Andrews, the ESPN reporter who was videoed while undressed

in her New York hotel room, allegedly by Michael Barrett, apparently now

convicted? This video too was circulated on the internet; the case made

headlines in July 2009 (though when the videos were actually taken is

unclear). Barrett got Andrews' room number from the hotel, reserved a room

next to hers, and either modified the door peephole somehow, or drilled a

hole through the wall and added a new peephole.

Is Andrews' situation any different from Clementi's? (Aside from the part

about damages to hotel property).

What should the law say here? Is

it wrong to place security cameras on your business property? Is it wrong to

place "nannycams" inside your house? What sort of notice do you have to give

people?

When we record the ACM lectures at Loyola, what sort of notice do we have to

give the audience? The speakers?

Note that in Illinois it was a felony to record conversations

without the consent of all parties, even in a public place. Here is a note

about the New Jersey law.

Note:

Under New Jersey's invasion-of-privacy statutes, it is a fourth degree

crime to collect or view images depicting nudity or sexual contact

involving another individual without that person's consent, and it is a

third degree crime to transmit or distribute such images. The penalty for

conviction of a third degree offense can include a prison term of up to

five years.

New Jersey lists "nudity" and "sexual contact" as entitled to privacy; some

other states list "expectation of

privacy".

If Clementi killed himself simply because he had been "outed", then any sex

partner could have outed him legally.

Sex partners could not legally have filmed him without his consent, but

(like most celebrity sex tapes) a lover could later release a tape that had been made with consent, or simply

release a textual narrative.

Ravi was convicted on March 16, 2012 for the invasion of privacy and for

"bias intimidation"; the latter is commonly known as the "hate crimes"

statute. He was then sentenced to 30 days in jail, plus fines and probation.

Ravi was not charged with provoking the suicide itself.

Pennsylvania school laptops

In the Lower Merion school district in Ardmore PA, school-owned laptops were

sent home with students. School officials were accused in 2010 of spying on

students by turning on the laptops' cameras remotely, while the laptops were

in the students' homes.

The school's position is that remote camera activation was only done when

the laptop was reported lost or stolen, as part of the LANRev software

package (see also the open-source preyproject.com

site). Note that the current owners of LANRev now state:

We discourage any customer from taking

theft recovery into their own hands," said Stephen Midgley, the

company's head of marketing, in an interview Monday. "That's best left

in the hands of professionals."

Some sources:

Parents became aware of the incident when Blake Edwards, then 15, was called

into the principal's office:

The Robbinses said they learned of the

alleged webcam images when Lindy Matsko, an assistant principal at

Harriton High School, told their son that school officials thought he had

engaged in improper behavior at home. The behavior was not specified in

the suit.

"(Matsko) cited as evidence a photograph from the webcam embedded in minor

plaintiff's personal laptop issued by the school district," the suit

states. [AP article]

Ms Matsko had seen the student ingesting something that looked to her like

drug capsules; the student in question claimed it was Mike-and-Ike

candy and there was considerable corroborating evidence that that was the

case. It is not clear whether Matsko had formally disciplined the student.

Supposedly the laptop camera was activated because the laptop was reported

as missing, but that in the case in question Robbins had, according to the

school district, been issued a "loaner" laptop because he had not paid the

insurance fees for a regular laptop. Loaner laptops were not supposed to go

home with students, but it is not clear that Robbins was ever told that.

Furthermore, there were about two weeks' worth of photos collected by the

webcam, despite Robbins' regular attendance at school.

Some technical details, including statements made by Mike Perbix of the

school's IS department, are available at http://strydehax.blogspot.com/2010/02/spy-at-harrington-high.html.

The stryde.hax article made the following claims:

- Possession of a monitored Macbook was required for classes

- Possession of an unmonitored personal computer was forbidden and would

be confiscated

- Disabling the camera was impossible

- Jailbreaking a school laptop in order to secure it or monitor it

against intrusion was an offense which merited expulsion

The first, if true, would seem odd, in that generally students also have the

option of using school computing labs plus home computing resources; the

other points are fairly standard (though black electrical tape is

wonderfully effective at disabling what the camera can see).

The Strydehax article also makes it clear that Perbix had gone to some

lengths to disable the camera for student use, but to still allow the camera

to be used by the administrative account. Perbix had written on https://groups.google.com/group/macenterprise/browse_thread/thread/98dd9da15da4189f/d461836b9996c4d8?lnk=gst&q=perbix+isight

(google login may be necessary):

[to disable the iSight camera] You have can

simply change permission on 2 files...what this does is prevent internal

use of the iSight, but

some utilities might still work (for instance an external application

using it for Theft tracking etc)...I actually created a little Applescript

utility and terminal script which will allow you to do it remotely, or

allow a local admin to toggle it on and off.

Some students noticed that the LED by the camera occasionally blinked or

came on. They were apparently told this was a glitch, and not that the

camera was tracking them (student testimonials in this regard are on the

Strydehax site).

Before the laptops were even handed out, Perbix had replied to another

employee's concern with the following (from wikipedia):

[T]his feature is only used to track

equipment ... reported as stolen or missing. The only information that

this feature captures is IP and DNS info from the network it is connected

to, and occasional screen/camera shots of the computer being operated....

The tracking feature does NOT do things like record web browsing,

chatting, email, or any other type of "spyware" features that you might be

thinking of.

Note that public schools are part of the government, and, as such, must

abide by the Fourth Amendment (though schools may be able to search lockers

on school property). (Loyola, as a

private institution, is not so bound, though there are also several Federal

statutes that appear to apply.)

Students and parents do sign an Acceptable Use policy. However, a signature

is required for the student to be issued a laptop. Also, students are

minors, and it appears to be the case that parents are not authorized to

sign away the rights of minors.

A second student, Jalil Hasan, also had his webcam activated. He had

apparently lost his laptop at school; it was found and he retrieved it a

couple days later. However, his webcam was now taking pictures, and

continued to do so for two months.

In April 2010 the school's attorneys issued a self-serving report claiming

there was no "wrongdoing", but nonetheless documenting rather appalling

privacy practices. Some information from the report is at http://www.physorg.com/news192193693.html.

The most common problem was that eavesdropping was not terminated even after

the equipment was found.

In October 2010, the Lower Merion School District settled the Robbins and

Hasan cases for $610,000. Of that amount, 70% was for attorneys' fees.

The FBI did investigate for violations of criminal wiretapping laws.

Prosecutors eventually decided not to bring any charges. While there may not

have been criminal intent, the policies of the school and its IT group

showed a gross disregard for basic privacy rights. While "accidentally"

taking pictures remotely might be a possibility, going ahead and then using

those pictures (eg to discipline students, or even to share them with

teachers and academic administrators) is a pretty clear abuse of privacy

rules.

Another school-laptop case

Susan Clements-Jeffrey, 52-year-old long-term substitute teacher at Keifer

Alternative School (K-12) in Springfield OH, bought a used laptop from

one of her students in 2008. She paid $60 for it. That's cheap for a laptop,

but the non-free application software had been removed and, well, the case

sort of hinges on whether it was preposterously

cheap. The lowest prices I could find a couple years later for used laptops

were ~$75, on eBay.

The laptop in fact had been stolen from Clark County School District in

Ohio, and on it was LoJack-for-Laptops software to allow tracking. Once it

was reported missing, the tracking company, Absolute

Software, began tracking it. Normal practice would have been to track

it by IP address (the software "phones home" whenever the computer is

online, and then turn that information over to the police so they could find

out where it was located, but Absolute investigator Kyle Magnus went

further: he also recorded much communication via the laptop (including audio

and video).

Clements-Jeffrey used the laptop for "intimate" conversation with her

boyfriend. Absolute recorded all this, including at least one nude image of

Clements-Jeffrey from the webcam. Police eventually did come and retrieve

the laptop; theft charges were quickly dropped.

Clements-Jeffrey, however, has now sued Absolute for violation of privacy,

under the Electronic Communications Privacy Act that forbids interception of

electronic communication. Absolute's defense has been that Clements-Jeffrey

knew or should have known the laptop was stolen, and if she had in fact

known this then her suit would likely fail. However, it seems likely at this

point that she did not know this.

Absolute has also claimed that they were only acting as agent of the

government (ie the school district). The school district denies any

awareness that eavesdropping might have been done. And claiming that actions

on behalf of a school district are automatically "under color of law" seems

farfetched to me.

In August 2011, US District Judge Walter Rice ruled that Clements-Jeffrey's

lawsuit against Absolute could go forwards. In September there was an

undisclosed financial settlement.

More at http://www.wired.com/threatlevel/2011/08/absolute-sued-for-spying.

More on laptops and spying

This is continuing, though schools are not involved in the exploits

documented here:

http://www.wired.com/threatlevel/2012/09/laptop-rental-spyware-scandal/

Event data recorders in automobiles

Who owns the data? Should you know it is there?

What if it's explained on page 286 of the owners manual? Or on page 286 of

the sales contract, incorporated by reference (meaning they don't print that

out)

Should it be possible for the state to use the information collected against

you at a trial? What about the vehicle manufacturer, in a lawsuit you have

brought alleging manufacturing defects?

See Wikipedia: "Event_data_recorder"

Of perhaps greater concern, data recording in automobiles has since 2010

switched more and more to online connectivity. There is often no opt-out

feature. Most new cars now transmit data to the manufacturer in

real time. This includes information about the following:

- Vehicle engine performance

- Driving: how hard is the braking, turning and acceleration

- Phone calls placed through the vehicle

- Music preferences

- Location (via in-car GPS)

Connecting your phone via bluetooth introduces new privacy risks.

Generally you are asked if it is ok to upload your contact list; if you

agree, your car has that list in perpetuity. Also, probably, the car's

manufacturer. And possibly a log of all SMS messages you've ever sent or

received. Data can also be harvested if you plug your phone into the

vehicle USB port, simply to charge it.

Typical user "agreements" allow the manufacturer to sell any data they

collect to anyone. The US Customs and Border Protection agency doesn't buy

this data from manufacturers, however; they've purchased equipment to read

it directly from cars: theintercept.com/2021/05/03/car-surveillance-berla-msab-cbp.

For an overview, see washingtonpost.com/technology/2019/12/17/what-does-your-car-know-about-you-we-hacked-chevy-find-out.

Facebook and privacy

Is Facebook the enemy of privacy? Or is Facebook just a tool that has

allowed us to become the enemies of our own privacy?

Originally, access was limited to other users in your "network", eg

your school. That was a selling point: stuff you posted could not leak to

the outside world. Then that changed. Did anyone care?

Facebook privacy issues are getting hard

to keep up with! For example, what are the privacy implications of Timeline?

Switching to Timeline doesn't change any permissions, but all of a sudden

it's much easier for someone to go way back in your profile.

Facebook knows a lot about you. It

knows

- who your friends are

- what you are writing to whom (using facebook)

- your age

- your education

- your job (probably)

- your hobbies

- what you "like"

- whether you are outgoing (extraverted?) or not

Here's a timeline of the progressive privacy erosion at facebook: eff.org/deeplinks/2010/04/facebook-timeline

At one time (2009?) Facebook was actively proposing "sharing" agreements

with other sites, and made data-sharing with those sites the default. The

idea was that FB and the other site would share information about what you

were doing. Some of the sites (from

readwriteweb.com) are:

- yelp.com: a restaurant/shopping/etc

rating site (so you could post about restaurants to both yelp and FB?)

- docs.com: a googledocs competitor owned

by Microsoft (presumably the idea was you could post "docs" on your FB

page)

- pandora.com (the web-radio site)

Eventually Facebook has again stepped back from a full roll-out of the

sharing feature, although the shared-login feature seems to be coming back.

Facebook has long tinkered with plans for allowing a wide range of

third-party sites to have access to your facebook identity. Back in 2007,

this project was code-named Beacon.

Supposedly the Beacon project has been dropped, but it seems the idea behind

it has not.

Ironically, third-party sites might not need

Facebook's cooperation to get at least some information about their

visitors (such as whether they are even members of Facebook). Your browser

itself may be giving this away. See

http://www.azarask.in/blog/post/socialhistoryjs.

(Note that this technique, involving the third party's setting up

invisible links to facebook.com, myspace.com, etc, and then checking the

"link color" (doable even though the link is invisible!) to see if the

link has been visited recently, cannot reveal your username.)

In May 2010 Facebook made perhaps

their most dramatic change in privacy policy, when they introduced changes requiring that some of your information

be visible to everyone: your name, your schools, your interests, your

picture, your friends list, and the pages you are a "fan" of. Allegedly your

"like" clicks also became world-readable. (Here's an article by Vadim

Lavrusik spelling out why this can be a problem: http://mashable.com/2010/01/12/facebook-privacy-detrimental.

Lavrusik's specific concern is that he sometimes joins Facebook groups as

part of journalistic investigation, not out of any sense of shared interest.

But journalists always have these sorts of issues.)

After resisting the May 2010 uproar for a couple weeks, Facebook once again

changed. However, they did not

apologize, or admit that they had broken their own past rules.

Here's an essay from the EFF, http://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2010/05/facebook-should-follow,

entitled Facebook Should Follow Its Own

Principles, in which they point out that Facebook's 2009 principles

(announced after a similar uproar) state

People should have the freedom to decide

with whom they will share their information, and to set privacy controls

to protect those choices.

But Facebook's initial stance in 2010 was that users always had the freedom

to quit facebook if they didn't like it. Here's part of Elliot

Schrage, FB VP for Public Policy, as quoted in a May 11, 2010 article at http://bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/05/11/facebook-executive-answers-reader-questions:

Joining

Facebook is a conscious choice by vast numbers of people who have

stepped forward deliberately and intentionally to connect and share. We

study user activity. We've found that a few fields of information need to

be shared to facilitate the kind of experience people come to Facebook to

have. That's why we require the following fields to be public: name,

profile photo (if people choose to have one), gender, connections (again,

if people choose to make them), and user ID number.

Later, when asked why "opt-in" (ie initially private) was not the default,

Schrage said

Everything is opt-in on Facebook.

Participating in the service is a choice. We want people to continue to

choose Facebook every day. Adding information -- uploading photos or

posting status updates or "like" a Page -- are also all opt-in. Please

don't share if you're not comfortable.

That said, much of your core information is still public by default.

Facebook has moved to a default setting for posts of "share only

with friends".

Two weeks after Schrage's claim that users would always be free not to use

Facebook if they didn't like it, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg weighed in,

with a May 24, 2010 article in the

Washington Post: http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/37314726/ns/technology_and_science-washington_post/?ns=technology_and_science-washington_post.

In the article, Zuckerberg does not seem to acknowledge that any mistakes

were made. He did, however, spell out some Facebook "principles":

- You have control over how your information is

shared.

- We do not share your personal information with

people or services you don't want.

- We do not give advertisers access to your

personal information.

- We do not and never will sell any of your

information to anyone.

- We will always keep Facebook a free service for

everyone.

The first principle is a step back from the corresponding 2009 principle.

Facebook vigorously claims that your information is not shared with

advertisers, by which they mean that your name is not shared. However, your

age, interests, and general location (eg town) are

shared, leading to rather creepy advertisements at best, and cases where

your identity can be inferred at worst.

Recall that advertisers are Facebook's real customers. They are the ones who

pay the bills. The users are just users.

Deja News, once at deja.com (now run by google): where is it now? It still

lets you search archives of old usenet posts, though the social significance

of that is reduced in direct proportion to the reduced interest in Usenet.

Think of being able to search for someone's years-old facebook posts, though

(and note that Facebook Timeline has in effect enabled just this).

Facebook

news-feeds

Baase 4e p 76 / 5e p 69

Originally, you only saw what your friends did when you reloaded their page.

News feeds (mini-feeds) implemented active

notification to your friends whenever you change your page. Why was this

considered to be a privacy issue? Is it still considered to be a privacy

issue?

The mini-feed issue originally came up in 2006. However, modifications of

the feature still occasionally reopen the privacy issue. At this point,

though, most people have come to accept that nobody understands when their

posts appear in someone else's post feed.

Is this a privacy issue or not?

Here's a view at the time, from theregister.co.uk/2006/09/07/facebook_update_controversy:

Users protest over 'creepy' Facebook update

The introduction of new features on social

network site Facebook has sparked a backlash from users. Design changes to

the site violate user privacy and ought to be scrapped, according to

disgruntled users who have launched a series of impromptu protests. One

protest site is calling for users to boycott Facebook on 13 September in

opposition against a feature called News Feed, which critics argue is a

Godsend for stalkers.

Would you say, today, that your Facebook newsfeed is "creepy"?

Whatever one says about Facebook and the loss of privacy, it is pretty

clear to everyone that posting material to Facebook is

under our control, though perhaps only in the sense that we

participate in Facebook voluntarily. Thus, the Facebook privacy question

is really all about whether we can control

who knows what about us, and continue

to use Facebook.

(Facebook does track all visitors, Facebook users or not, on

any web page with an embedded Facebook "like" button, but that's a

separate issue.)

Cambridge Analytica

Suppose Alice tells Bob a secret. Bob then goes to a party at Zuck's and

tells Charlie. How angry at Charlie should Alice get? At Zuck?

Aleksandr Kogan developed a Facebook quiz app, "This Is Your Digital

Life", in 2013. By 2015, some 300,000 Facebook users took it. The terms of

service granted access to the user's Facebook data, at least to the basic

data. That included the information about your friends that they had made

available to you.

The quiz was actually administered by Cambridge Analytica. Due to the

friends amplification, they obtained information on somewhere between 30

and 87 million Facebook users.

Cambridge Analytica used the data collected to try to identify the

political leanings of each person for whom they obtained data, and also to

identify the political issues the person would be most interested in.

The Obama campaign had tried something similar, but users were fully

aware that they were granting information to a political organization. The

This Is Your Digital Life quiz had no indication that it was anything

other than any of those many "harmless" quizzes on Facebook.

The 2016 Trump campaign hired Cambridge Analytica; the data was used in

that campaign.

Should Facebook ever have let outside "apps" access data on

Friends? They stopped this in 2014, but Kogan's app was grandfathered in.

Data from the app was supposed to be deleted, but Facebook didn't make an

effort to confirm this. In 2018, Facebook cracked down much harder on apps

being allowed access to any Friend data at all (though it's not clear it's

blocked completely).

It is unlikely the data was of much use in the 2016 campaign. Both

political parties provide the same information, in much more usable and

accurate form. And it has limited utility in getting people to vote, and

very limited utility in getting people to change their vote.

Facebook and unrelated sites

Facebook now shows up on unrelated sites. Sites are encouraged to enable the

Facebook "like" button, and here's an example of theonion.com displaying my

(edited) friends and their likes: http://pld.cs.luc.edu/ethics/theonionplusFB.html.

How much of this is an invasion of privacy?

While Facebook does seem interested in data-sharing agreements with non-FB

sites, it is often not at all clear when such sharing is going on. The two

examples here, for example, do not necessarily involve any sharing. An

embedded "like" button, when clicked, sends your information to Facebook,

which can retrieve your credentials by using cookies. However, those

credentials are hopefully not

shared with the original site; the original site may not even know you

clicked "like". As for the box at theonion.com listing what my friends like,

this is again an example of "leased page space": Facebook leases a box on

theonion.com and, when you visit the site, it retrieves your FB credentials

via cookie and then fills in the box with your friends' "likes" of Onion

articles. The box is like a mini FB page; neither the likes nor your

credentials are shared with The Onion.

One concern with such pseudo-sharing sites is that they make it look like

sharing is in fact taking place, defusing objections to such sharing. If

someone does object, the fact that no sharing was in fact invoved can be

trotted out; if there are not many objections, Facebook can pursue "real"

sharing agreements with confidence. They also make it harder to tell when

objectionable sharing is occurring.

An example of a true data-sharing agreement would be if a restaurant-review

site let you log into their site

using your Facebook cookies, and

then allowed you to post updates about various restaurants.

Facebook "connections": http://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2010/05/things-you-need-know-about-facebook

Your connections are not communications with other users, but are links to

your school, employer, and interests. It is these that Facebook decided to

make "public" in May 2010; these they did back off from.

Facebook and Advertising

Facebook claims that user data is not turned over to advertisers, and

this seems true (with a couple slip-ups): advertisers supply criteria

specifying to whom their ads will be shown, and Facebook shows the ads to

those users. For example, a few years ago I would regularly see ads for

"Illinois drivers age 54", but this didn't mean that Facebook had turned

over my age. What happened is that the advertiser has created an ad for

each age 30-65, and asked Facebook to display to a user the one that

matches his or her age. This is misleading, but information is not shared

directly.

Since then, Facebook has disallowed this type of ad:

Ads must not contain content that

asserts or implies personal attributes. This includes direct or

indirect assertions or implications about a person’s race, ethnic

origin, religion, beliefs, age, sexual orientation

or practices, gender identity, disability, medical condition

(including physical or mental health), financial status, membership

in a trade union, criminal record, or name.

Once you click on an ad, however, the advertiser does know what ad you are

responding to, and thus would know your age in the example above.

There was a slip-up a couple years ago where game sites (often thinly veiled

advertising) were able to obtain the Facebook ID of each user. Here's what

they say:

In order to advertise on Facebook,

advertisers give us an ad they want us to display and tell us the kinds of

people they want to reach. We deliver the ad to people who fit those

criteria without revealing any personal information to the advertiser.

For more information on how to do this, see http://www.facebook.com/adsmarketing/index.php?sk=targeting_filters.

Facebook supports targeting based on:

- Location, as determined from your IP address

- Language (eg Spanish-speaking residents of the Chicago area)

- Age and sex

- Likes and Interests. I decided to "like" horseback riding several

years ago. It took a couple years for any related ads to show up, but

now they do so regularly.

- Connections: did someone Like your page? Did someone rsvp to your

event? Play your game? You can also target their Friends.

- Advanced Demographics: birthdays, schools and professions

Note that you don't get to choose what attributes advertisers can use,

because advertisers do not see them! And Facebook itself has access to

everything (duh).

For a while it was possible to specify the ad-selection terms very

precisely (including the use of the user's "network"), even to the point

of displaying an ad to a single user (though this was not supposed to

work). Here's a blog post from late 2017 on doing exactly this: medium.com/@MichaelH_3009/sniper-targeting-on-facebook-how-to-target-one-specific-person-with-super-targeted-ads-515ba6e068f6.

But this has now been fixed; see thetyee.ca/News/2019/03/06/Facebook-Flaw-Zero-In/.

Supposedly, post-Cambridge-Analytica, Facebook has cracked down on this

sort of thing. But it's hard to be sure what they did.

Targeting by email

Go to settings → ads (on left) → Advertisers and Businesses → Who

uploaded a list with your info and advertised to it.

What this means is that advertisers can target you on Facebook even if no

interests match. The uploaded lists can be based on email addresses, phone

numbers, Facebook UIDs, Apple or Android advertising IDs [!], or other.

See developers.facebook.com/docs/marketing-api/reference/custom-audience.

It is not very clear what Facebook does to prevent advertisers from

uploading huge email lists for Facebook to spam.

Also, Facebook does run a full-scale advertising network. Non-Facebook

websites include ads from this network, just as they include Google ads.

Facebook identifies that it's you by your Facebook browser cookie, and

serves up the ads.

Suggestions: don't give Facebook your regular email address. I know,

kinda late now.

For what it's worth, here are Facebook's basic advertising policies: facebook.com/policies/ads.

This targeting-by-email advertising category may account for a large

chunk of Facebook's advertising revenue, though Facebook doesn't publish

statistics.

Engagement

Facebook is able to provide evidence of engagement, typically with

organization pages, in ways that advertisers outside of Facebook and

Google cannot do (and maybe not even Google). See

In fact, it is possible to declare engagement to be the

objective of your ad campaign. You then get billed based, not on clicks,

but on the basis of a "page post engagement metric", including clicks,

likes, shares, comments and video views. (Some of these are considered active;

others passive.) For advertisers, this approach is often a good

deal. Advertisers end up paying for engagement rather than clickthroughs.

Facebook supports a complex system of advertising objectives. See facebook.com/business/ads-guide/image/facebook-feed/post-engagement.

Facebook is perhaps the only online advertiser that can measure

interaction (maybe Google can, through YouTube), because they both run the

site and serve up the ads.

Like → advertisement

FB "likes" have long been somewhat randomly displayed to Friends. But in

2012 FB added a new feature: social

advertisements, or Sponsored Stories.

If you "like" something on Facebook, it may automatically be converted to an

advertisement, paid for by the company whose product you liked.

Here's an example: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/01/technology/so-much-for-sharing-his-like.html?_r=2.

Nick Bergus discovered that Amazon was selling personal lubricant in

55-gallon-drum quantities, and posted a satirical "like". Actually, he

posted a comment. Much to Nick's surprise, his "comment" became part of an

ad for the product shown to his friends, paid for by Amazon; FB's policy is

that an advertiser may purchase any likes/comment it wishes and convert them

to paid ads, with no royalties to the liker. Such "social ads" are displayed

only to friends of the liker [if I understood this correctly]. Note,

however, that presumably none of Mr Bergus' friends would have been targeted

for this particular ad if Mr Bergus hadn't "endorsed" the product. Alas for

FB, Amazon and perhaps Mr Bergus, FB's ad-selection mechanism seems to be

clueless about the realities of sarcasm.

Here is the relevant part of the policy, from May 2012, still in place

October 2013:

10.

About Advertisements and Other Commercial Content Served or Enhanced

by Facebook

Our goal is to deliver ads that are not

only valuable to advertisers, but also valuable to you. In order to do

that, you agree to the following:

- You can use your privacy

settings to limit how your name and profile picture may be

associated with commercial, sponsored, or related content (such as a

brand you like) served or enhanced by us. You give us

permission to use your name and profile picture in connection with

that content, subject to the limits you place.

- We do not give your content or information to advertisers without

your consent.

- You understand that we may not always identify paid services and

communications as such.

In June 2012, Facebook agreed to make it clearer to users when this is

happening. The above policy is presumably the "clearer" policy.

Conversely, if you do not use your

privacy settings to limit how your identity may be used in ads, you have

agreed to such use!

Here are FB's

rules for social ads:

-

Social ads show an advertiser's message alongside

actions you have taken, such as liking a Page

-

Your privacy settings apply to social ads

-

We don't sell your information to advertisers

-

Only confirmed friends can see your actions alongside

an ad

-

If a photo is used, it is your profile photo and not

from your photo albums

I tried setting my social-ad preferences. I found them at Privacy

Settings → Ads, Apps and Websites → Ads → Edit Settings. My settings were

"no one"; I have no idea why.

Facebook and Political Ads

After Cambridge Analytica, Facebook increased its monitoring of political

ads. Much of the spending data is now public. To view it, start at the

Facebook Ad Library page, facebook.com/ads/library/?active_status=all&ad_type=political_and_issue_ads&country=US.

Search for "The People For Bernie Sanders". You have to get the

organization exactly right. Try typing the candidate name, and then using

the down-arrow.

It can be very hard to get the correct search term that identifies the

political organization, and thus the ad spending. You are looking for a

pair of boxes, the leftmost one titled "Total spent by Page on ads related

to politics or issues of importance". Alternatively, try these:

Facebook data

Some have argued that Facebook privacy issues have shifted: the data you

post is no longer the real issue at all (after all, more and more users are

comfortable with the control they have over that data). The real issue is

the data that Facebook collects from you in their role as an advertiser.

They know what you like, what you "like", and what you actually click on. In

some ways, this is similar to Google. In other ways, Facebook has those

pictures, and arguably even more metadata to play with.

See saintsal.com/facebook/

Facebook and privacy more fine-grained than the Friend level

What if you've Friended your family, and your school friends, and want to

put something on your wall that is visible to only one set? The original

Facebook privacy model made all friends equal, which was sometimes a bad

idea. Facebook has now introduced the idea of groups:

see http://www.facebook.com/groups.

Groups have been around quite a while, but have been repositioned by some

(with Facebook encouragement) as subsets of Friend pools:

Have things you only want to share with a

small group of people? Just create a group, add friends, and start

sharing. Once you have your group, you can post updates, poll the group,

chat with everyone at once, and more.

For better or worse, groups are still tricky to manage, partly because they

were not initially designed as Friend subsets. When posting to a group, you

have to go to the group wall; you can't put a message on your own wall and

mark it for a particular group. News feeds for group posts are sometimes

problematic, and Facebook does not make clear what happens if a group

posting is newsfed to your profile and then you Comment on it. You may or

may not have to update your privacy settings to allow group posts to go into

your newsfeed. Privacy Settings do not mention Groups at all (as of June

2011).

Maybe the biggest concern, however, is that Facebook's fast-and-furious

update tradition is at odds with the fundamental need to be meticulous when

security is important.

That said, some people are quite successful at using FB's privacy features

here.

Google+ came out with circles,

which promptly changed all this. FB has now introduced new competitive

features (groups), which I have been too lazy to bother with. (Part of the

issue is that FB groups were invented to deal with larger-scale issues; as

originally released they were an awkward fit for subsets of Friends.)

But the issue is not really whether they work.

Here's a technical analogue: are NTFS file permissions better than

Unix/Linux? Yes, in the sense that you can spell out who has access to what.

But NTFS permissions are very difficult to audit and to keep track of; thus,

in a practical sense, they have

been a big disappointment.

Facebook and Facial

Recognition

Does this matter?

Here's an article from August 2012: http://news.cnet.com/8301-1023_3-57502284-93/why-you-should-be-worried-about-facial-recognition-technology/,

and related articles linked to that.

Even today, Facebook appears to be using this technology to suggest how to

tag people in photos. Is this a concern? If the technology catches on, might

other uses make it become a concern? Could Facebook also be using this

technology to identify those who create Facebook accounts not using their

real name?

Here's a 2015 article: FaceBook

will soon be able to ID you in any photo

The article here is from the publishers of Science.

FaceBook is way ahead of the FBI in this regard.

Facebook has claimed that this new feature will protect your

privacy: "you will get an alert from Facebook telling you that you appear in

the picture,.... You can then choose to blur out your face from the picture

to protect your privacy." Is that likely? After all, if you're tagged

in the picture then they don't need facial recognition, and if you're not

tagged, is this a serious issue?

FaceBook's DeepFace system was trained on all those FB pictures in which

people are tagged. Did you know you agreed to that?

Police could use such a system to identify people on the street, or

participants at a rally. Stalkers could use it to find out the real identity

of their chosen victim.

Facebook does not make their entire face library public, though they do

make profile pictures public. Vkontakte, in

Russia, apparently makes more images public, and a facial-identification

app FaceFind has been created using Vkontakte's image library. Given a

picture of a person (even in a crowd), it supposedly can identify the

person around 70% of the time. See https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/may/17/findface-face-recognition-app-end-public-anonymity-vkontakte.

Clearview is now available in the US; it is a

similar facial-identification tool. Officially, Clearview is only

available to the police, and maybe also to those who consider themselves

to be "investigators".

Finally, here is a lengthy essay by Eben Moglen, author of the GPL, on

"Freedom in the Cloud: Software Freedom, Privacy, and Security for Web 2.0

and Cloud Computing": http://www.softwarefreedom.org/events/2010/isoc-ny/FreedomInTheCloud-transcript.html.

Mr Moglen adds some additional things that can be inferred from

Facebook-type data:

- Do I have a date this Saturday?

- Who do I have a crush on (whose page am I obsessively reloading)?

You get free email, free websites, and free spying too!

Mr. Zuckerberg has attained an unenviable

record: he has done more harm to the human race than anybody else his age.

Because he harnessed Friday night. That is,

everybody needs to get laid and he turned it into a structure for

degenerating the integrity of human personality and he has to a remarkable

extent succeeded with a very poor deal. Namely, 'I will give you free web

hosting and some PHP doodads and you get spying for free all the time'.

And it works.

Later:

I'm not suggesting it should be illegal. It

should be obsolete. We?re technologists, we should fix it.

Did Google+ fix anything? Does anyone trust google more than Facebook?

Google+ circles do seem easier to use.

Facebook 2010 settings

Here are some of the June 2010 Facebook privacy settings (that is, a month

after the May 2010 shift), taken from privacy settings ? view settings

(basic directory information). Note that there is by this point a clear

Facebook-provided explanation for why some things are best left visible to

"everyone".

At the time I collected these, the issue was that FB provided explanations,

and defaults. In retrospect, the issue is what happened to all these

settings?

Your name, profile picture, gender and

networks are always open to everyone. We suggest leaving the other basic

settings below open to everyone to make it easier for real world friends

to find and connect with you.

* Search for me on Facebook

This lets friends find you on Facebook. If you're visible to fewer people,

it may prevent you from connecting with your real-world friends.

Everyone

* Send me friend requests

This lets real-world friends send you friend requests. If not set to

everyone, it could prevent you from connecting with your friends.

Everyone

* Send me messages

This lets friends you haven't connected with yet send you a message before

adding you as a friend.

Everyone

* See my friend list

This helps real-world friends identify you by friends you have in common.

Your friend list is always available to applications and your connections

to friends may be visible elsewhere.

Everyone

* See my education and work

This helps classmates and coworkers find you.

Everyone

* See my current city and hometown

This helps friends you grew up with and friends near you confirm it's

really you.

Everyone

* See my interests and other Pages

This lets you connect with people with common interests based on things

you like on and off Facebook.

Everyone

Here are some more settings, from privacy settings => customize settings

(sharing on facebook)

* Things I share

| Posts by me (Default setting for posts, including status updates

and photos) |

Friends Only |

| Family |

Friends of Friends |

| Relationships |

Friends Only |

| Interested in and looking for |

Friends Only |

| Bio and favorite quotations |

Friends of Friends |

| Website |

Everyone |

| Religious and political views |

Friends Only |

| Birthday |

Friends of Friends |

.

* Things others share

| Photos and videos I'm tagged in |

Friends of Friends |

| Can comment on posts |

Friends Only |

| Friends can post on my Wall |

Enable |

| Can see Wall posts by friends |

Friends Only |

* Contact information

o Friends Only

The core problem here is not that these settings are hard to do, or that the

defaults are bad. The core problem is simply that you keep having to make new settings, as things evolve.

Examples:

- whether you can be tagged in other people's photos

- whether FB facial-recognition software is applied to other people's

photos of you

- whether you appear in other people's mini-feeds on you

- how far can friends search back in time on your wall

Another issue is whether the settings options are user-friendly. Here's a

technical analogue: are NTFS file permissions better than Unix/Linux? Yes,

in the sense that you can spell out who has access to what. But NTFS

permissions are very difficult to audit and to keep track of; thus, in a practical sense, they have been a huge

disappointment.

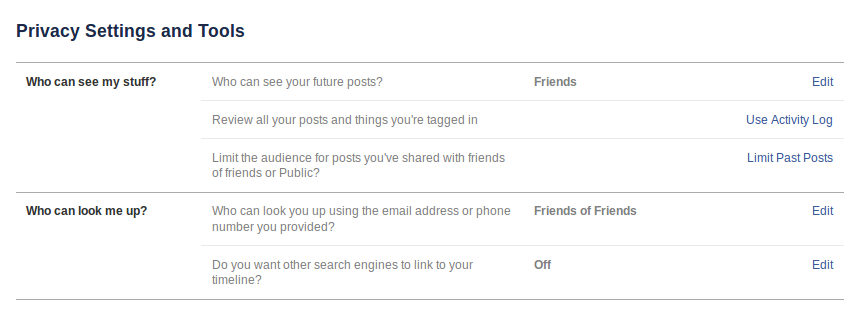

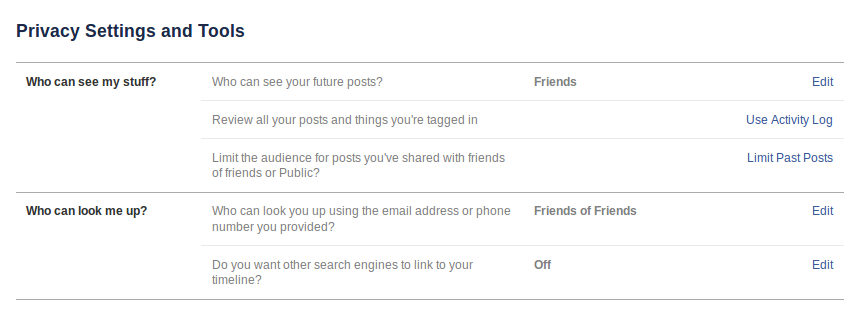

Facebook 2013 Settings

Facebook's current (2013) settings are, if anything, a step

towards greater inscrutability, though the new settings are

briefer. You are only given options to control who can see your posts

and who can look you up. (Photo albums have their own controls.)

Whether others can see your friend lists, or your personal information, is

no longer something you can control directly.

Later in 2013, a section "Who can contact me" was added, with options for

controlling who can send you Friend requests and who can send you messages.

The mechanism for limiting people from seeing past posts on your

timeline turns out never to be explained, and there are dire warnings

against even using it:

Limit The Audience for Old Posts on Your Timeline

If you use this tool, content on your timeline

you've shared with friends of friends or Public will change to

Friends. Remember: people who are tagged and their friends may see

those posts as well. You also have the option to individually change

the audience of your posts. Just go to the post you want to change

and choose a different audience.

Limit Old Posts

If you click the last thing, you get

You are about to limit old posts on your

timeline without reviewing them. Note: This global change can't

be undone in one click. If you change your mind later, you'll

need to change the audience for each of these posts one at a time.

You do now have a rather different way to review posts and photos by others

that you are tagged in.

You also have greater control over visibility of specific posts.

You can set the visibility of your friends list by going to friends =>

edit.

You can set the visibility many of 2010's "Things I share" by going to the

individual shared item and editing its sharing status. That is, sharing

policy is no longer all in one place; it is associated with each separate

item shared instead.

As far as I can tell, there is no longer a distinction between permission to

"post on your wall" and permission to "comment on a post".

And see http://www.facebook.com/help/204604196335128/,

for other lists of friends, including your "close friends" list. (Who can

see your "close friends" list?)

Facebook Elections

Facebook called for a policy-change election in December 2012. 79,731 voted

for the policy change; 589,141 voted against. Facebook officially declared,

however, that they required 30% participation (~300 million people!) to make

the vote binding.

Facebook decided to ignore the Will Of The Users.

They also, as part of the process, abandoned user voting.

Security researcher Suriya Prakash

discovered how to get your phone number from Facebook.

It turns out that Facebook allows by default a search for your page given

your phone number. You can turn this off, but (once again) only

if you know it is on. (It is in the privacy-settings category "How

you connect", which is rather misleading.)

So the idea is to search for all numbers, 000-000-0000 to 999-999-9999 and

get the name of each user. Then sort the table by name. All this is quite

practical; Prakash has said he has a table of about 5 x 108

numbers.

(Normally, if you're going to allow looking people up using an identifier

that isn't meant to be public, you implement a rate-limit on searches

per second, to disable Prakash's idea. Facebook failed to do this.)

If you know the area code, you can refine the search easily.

Get Your Loved Ones Off Facebook

That's the title of a famous

blog post by Salim Virani. Does he overstate the case? Or is Facebook

really dangerous?

Facebook does appear to follow your privacy preferences when you post

things. But that's not the whole story.

It is true that Facebook changes their Terms of Service and Privacy Rules

regularly. You don't get notifications of these changes. Is that bad?

Here are some things that Virani documents, though, that not everyone is

aware of:

- Facebook collects a lot of information about you outside of

what you upload or post. This information they are much freer to use

(and misuse). Generally, Facebook appears to keep "Like" clicks in this

category. Facebook has long created "social advertising" based on your

Likes (#facebook_advertising)

- If a non-Facebook page has an embedded Facebook "Like" button (or any

other FB applet), then Facebook can track that you've been to that page.

Lots of advertisers can track you this way, but only Facebook (and

Google, if you're logged in to your google account) can identify

you.

- Facebook is pushing to have most posted videos within the Facebook

system. This way Facebook can track exactly how much you watched, and

doesn't give up any advertising revenue to YouTube.

- Facebook's facial recognition system appears to be impossible to opt

out of. Even if you're not a Facebook user.

- The Facebook smartphone app tracks your location. It also enables

the microphone (at least, you have to grant it that permission to

install the app on Android). Lots of apps demand the ability to enable

the microphone. What are they all using it for? What is Facebook using

this for? The original theory was that they wanted to monitor what TV

shows you had on in the background.

- Facebook has a very accurate personality model for you.

- Facebook sometimes shows you little surveys

that look legitimate but are really intended to discover if any of your

friends are using fake names. But Facebook does not necessarily close

those accounts.

- If you're not on Facebook, they probably maintain an account for you

anyway, so they have a single identifier by which to index all those

photos of you that other people post. And any other information other

people post about you.

Some of the concerns expressed by Virani are unproven. But they all are

definitely plausible. Do you care?

Data Bureaus

If it's called a credit bureau, they keep track of your

credit-worthiness. In the US, credit reports are based on payment history,

almost entirely. There are three main credit bureaus: Equifax, Experian

and Trans-Union.

Use of this information for non-credit purposes, such as car

insurance, health insurance and employment, is often illegal, and in any

jurisdiction you have to be informed if you are denied a service based on

a negative credit report. So there is a great deal of interest in being

able to buy "credit-like" reports that are not called credit

reports. Hence the rise of data bureaus, which sell the

same data as credit bureaus, but, because they do not use the word

"credit" in their reports, they (and their customers) are not required to

comply with the rules that cover credit reporting.

SocialIntel

How about this site: Social Intelligence Corp, www.socialintel.com.

What they do is employee background screening. They claim to take some of

the risk out of do-it-yourself google searches, because they don't include

any information in their report that you are not supposed to ask for. What

they do is gather all the public Facebook information about you (and also

from other sources, such as LinkedIn), and store it. They look, in

particular, for

- racially insensitive remarks, such as that English should be the

primary language in the US

- membership in the Facebook group "I shouldn't have to press 1 for

English. We are in the United States. Learn the language."

- sexually insensitive remarks or jokes or links

- displays of weaponry, such as your Remington

.257 hunting rifle or your antique Japanese katana sword

While they do not offer this upfront, one suspects they also keep track of

an unusually large number (more than four?) of drunken party pictures.

Think you have no public Facebook information, because you share only with

Friends? Look again: the information does not have to have been posted by

you. If a friend posts a picture of you at a party, and makes the album

world-viewable, there may have gone your chance for that job at Microsoft.

To be fair, Social Intelligence is still fine-tuning their rules; the latest

version appears to be that they keep the information for seven years, but

don't release it in a report unless it's still online at the time the report

is requested. Unless things

change, and they need to go back to the old way to make more money.

In June 2011 the FTC ruled that Social Intelligence's procedure was in

compliance with the Fair Credit Reporting Act.

See:

Is this a privacy issue?

SocialIntel was one of the first companies to harvest Facebook data, selling

it mostly to prospective employers. There are now a large number of firms

that specialize in collecting Facebook public data, analyzing it, and

selling "threat reports" to police departments and private security-related

firms. See http://littlesis.org/news/2016/05/18/you-are-being-followed-the-business-of-social-media-surveillance/.

One company, ZeroFox, allegedly

tracked Black Lives Matter protesters. A similar company, Geofeedia,

also has police contracts. Both firms do a significant amount of commercial

"reputation management" work as well.

The big "mainstream" data bureaus are ChoicePoint

and Acxiom. (ChoicePoint is now LexisNexis.com/risk

(for Risk Solutions)) (Baase 5e p 63ff)

Look at the websites. Are these sites bad?

What if you are hiring someone to work with children? Do such employees have

any expectation of privacy with regard to their past?

ChoicePoint sells to government agencies data that those agencies are often

not allowed to collect directly. Is

this appropriate? (One law-enforcement option is their Accurint

database.)

ChoicePoint and Acxiom might argue that they are similar to a credit bureau,

though exempt from the rules of the Fair Credit Act because they don't

actually deal with credit information. Here is some of the data

collected (from Baase 3e):

- credit data

- divorce, bankruptcy, and other legal records

- criminal records

- employment history

- education

- liens

- deeds

- home purchases

- insurance claims

- driving records

- professional licenses.

(By the way, if a company offering you for a job pushes you hard to tell

them your birthdate, which is illegal for companies with four or more

employees, they are probably after it in order to search for

criminal-background data.)

Zhima Credit

Data collection could be worse. If you live in China, you probably pay

for things with Alipay (or WeChat Pay). Pretty much every transaction

leaves a record. The Alipay system allows icons (apps) within it. One of

them is Zhima (Sesame).

Zhima is a credit-score system. If you sign up, you get a credit score.

But it's not quite like the FICO score used in the US; there are lots of

additional factors. Some of these relate to a scoring system the Chinese

government was considering, called social credit. In

addition to whether you pay your bills on time (and pay government fines

on time), Zhima considers (or would like to consider) the following:

- What goods you buy

- Your education, and where you work

- Scores of your Friends (in Alipay)

- Whether you cheated on the college entrance exam

- Whether you failed to pay any fines

Your Zhima score is also public.

From Zhima: "Zhima Credit is dedicated to creating trust in a commercial

setting and independent of any government-initiated social credit system.

Zhima Credit does not share user scores or underlying data with any third

party including the government without the user's prior consent". Or,

perhaps, a government order.

Under the "social credit" system, people were supposed to have their

scores reduced if they were "spreading online rumors".

If your Zhima score is not excellent, you can still use many of the same

services, but you will have to provide a deposit. One car-rental agency

allows rentals without a deposit to those whose Zhima score is over 650

(new users start at 550). At one point, a score of over 750 let you bypass

the security scan at Beijing airport. High scorers also get preferential

placement on dating apps.

For a detailed article on Zhima, from a western perspective, see www.wired.com/story/age-of-social-credit.

It could be worse. Compare Zhima to the social surveillance faced by

the Uighur population of China's Xinjiang province:

nytimes.com/2018/02/03/opinion/sunday/china-surveillance-state-uighurs.html

Imagine that this is your daily life: While on

your way to work or on an errand, every 100 meters you pass a police

blockhouse. Video cameras on street corners and lamp posts recognize your

face and track your movements. At multiple checkpoints, police officers

scan your ID card, your irises and the contents of your phone. At the

supermarket or the bank, you are scanned again, your bags are X-rayed and

an officer runs a wand over your body....

A more detailed article is at www.engadget.com/2018/02/22/china-xinjiang-surveillance-tech-spread,

which also outlines the spread of the Chinese technology to other

authoritarian governments.

Social Credit Here

Could it happen here? The most likely is not a government-sponsored

system (though the TSA No-Fly list has some elements of this), but rather

a private system. Already Uber, Lyft and Airbnb ban certain users for

"inappropriate" behavior; these bans cannot be appealed. Insurance

companies are also collecting private "social credit" information about

potential customers. Some bar owners use PatronScan, a private blacklist

for bar patrons.

See fastcompany.com/90394048/uh-oh-silicon-valley-is-building-a-chinese-style-social-credit-system.

The International Monetary Fund published a blog post in 2020 suggesting

that incorporating your browsing history in your credit score would be a

good idea; see blogs.imf.org/2020/12/17/what-is-really-new-in-fintech.

The authors write:

Fintech resolves the dilemma [of traditional

credit scores of people with limited credit history] by tapping various

nonfinancial data: the type of browser and hardware

used to access the internet, the history of online searches and

purchases. Recent research documents that, once powered by

artificial intelligence and machine learning, these alternative data

sources are often superior than traditional credit assessment methods, and

can advance financial inclusion, by, for example, enabling more credit to

informal workers and households and firms in rural areas.

This would help some people who can't get a credit card because

they have no credit history, and can't get a credit history because they

have no credit card. But what searches would count as good? What would

count as bad? The blog authors claim AI will figure it out.

Arguably, the blog post was more of a "trial balloon" than a serious

proposal. One issue remaining is just how to associate names with browsing

history, with accuracy comparable to that typical of credit-history data.

But in general the banking industry is quite worried about "fintech"

moving to Amazon, Google and others.

But see www.extremetech.com/internet/326088-should-your-web-history-impact-your-credit-score-the-imf-thinks-so,

for a discussion of why machine learning is not going to be able to manage

this, and why the US would need a large expansion of regulation to be sure

banks were not abusing the feature.

The European Data Protection Supervisor (part of the EU) has advised

against using browsing data for credit scoring. They likewise advise

against the use of health information in credit scoring. The EDPS states

that the use of this kind of data "cannot be reconciled with the

principles of purpose limitation, fairness and transparency, as well as

relevance, adequacy or proportionality of data processing".

Facial Recognition

Facial recognition has been expanding much faster than the scope of our

regulations, or even social norms. Facial recognition has the potential to

end privacy when in public spaces.

Schools, sporting events, stores and restaurants are often concerned with

security in general. The AnyVision product is marketed to such places. It

can track the presence of unauthorized visitors to schools, of known

shoplifters to stores, and simply of repeat visitors. See themarkup.org/privacy/2021/07/06/this-manual-for-a-popular-facial-recognition-tool-shows-just-how-much-the-software-tracks-people

for examples of how such software is used.

The Chinese company TenCent now uses facial recognition to prevent minors

from playing certain games after hours, in order to comply with a national

game curfew. See www.nytimes.com/2021/07/08/business/video-game-facial-recognition-tencent.html.

Because teens sometimes use parents' phones, the technology is used for everyone.

Facial recognition used to have a strong racial bias: African-American

faces were much likely to result in false-positive matches; that is,

innocent people were identified as matches to the suspect. This was

apparently due to the fact that training data consisted almost entirely of

white and Asian faces. This bias has supposedly largely been fixed. That

said, note this article, which claims that, well, here's the August 2023

title:

In

every reported case where police mistakenly arrested someone using

facial recognition, that person has been Black

Some times, virtually no followup analysis was done after a

facial-recognition match before issuing a warrant. Porcha Woodruff was

arrested after a false match, despite being eight months pregnant, while

the suspect was clearly not pregnant at all: www.nytimes.com/2023/08/06/business/facial-recognition-false-arrest.html.

Clearview

Clearview is a program that attempts

to identify people from a photograph. In this it is much like Facebook's DeepFace (internal to Facebook)

or VKontakte-based FaceFind (available to the public, but covering only

Russia). [There is also Amazon's Rekognition.] The idea is that billions

of identified facial photos have been processed, so that, when the system

is presented with a new face photo, it can quickly find the best match.

Clearview is marketed primarily to law enforcement, though the company

also makes its product available to selected other "investigators". It is

not clear if there is anyone, in fact, that the company will not

sell to, when asked.

Clearview argues that its product is a kind of search engine: you give it

a picture, and it finds a match. However, it is quite different from

Google's image search, which is intended only to find exact matches of a

given image. There is a tremendous amount of complex image analysis that

goes into finding a face match.

Perhaps the most controversial part of Clearview is how they got their

~3-billion-image dataset: they scraped it from the web. On Facebook, your

profile picture (which you do not have to include) is public, as is your

name. Clearview also scraped from Google, YouTube, Twitter, Venmo and

others, and from millions of personal web pages (which many people still

have, if only as a blog). This may violate the announced "Terms of

Service" of many of the sites, but those terms are only binding if you

have to accept them as a condition of accessing the site. (That might

be true of Facebook, which has sued Clearview for ToS violations.)

Clearview has stated it has a "first amendment right" to make use of the

facial data it has scraped. Legally, if they have a picture of you

together with your name, there is no clear legal argument for blocking

their use of it.

For an overall summary, see engadget.com/2020/02/12/clearview-ai-police-surveillance-explained.

Clearview's customer list was leaked in February 2020. Clients include

the Justice Department, ICE, and the Chicago Police Department (on a trial

basis). However, it has many commercial clients, presumably for either

customer profiling or for shoplifting investigation. These clients include

Wal*Mart, Best Buy, Macy's, Kohls and the NBA. See buzzfeednews.com/article/ryanmac/clearview-ai-fbi-ice-global-law-enforcement.

Before Clearview became well-known, it was widely available to wealthy

individuals and to corporations with little clear need for facial

recognition, as the company sought investors; see nytimes.com/2020/03/05/technology/clearview-investors.html.

See also "Your Face Is Not Your Own", www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/03/18/magazine/facial-recognition-clearview-ai.html.

Tinder

The popular dating app Tinder keeps a large amount of potentially very

sensitive information about its users. In 2017, journalist Judith

Duportail invoked her EU right to her Tinder records. It amounted to 800

pages. She writes:

At 9.24 pm (and one second) on the night of

Wednesday 18 December 2013, from the second arrondissement of Paris, I

wrote “Hello!” to my first ever Tinder match. Since that day I’ve fired up

the app 920 times and matched with 870 different people. I recall a few of

them very well: the ones who either became lovers, friends or terrible

first dates. I’ve forgotten all the others. But Tinder has not. [www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/sep/26/tinder-personal-data-dating-app-messages-hacked-sold]

In particular, Tinder remembers all the messages. It is not just the

sexual ones that are revealing; people often say very personal things to

new partners, as part of establishing intimacy.

Tinder has not, as far as we know, yet been hacked. But what happens if when it is?

Should Tinder be subject to any special regulations concerning its stored

data? Should they be allowed to change the terms of service as applied to

past data? Should the current terms of service be binding on any

company that might purchase Tinder? What should the rules be for police

access?

Managing Your Online Privacy

The article linked to here is about the idea that younger adults --

so-called Generation Y -- might (or might not) be more aware about how to manage

their FaceBook privacy, and by the same token to be less strict about what

they expose online.