Privacy from the Government

Readings:The next segment we will do is on Privacy. Start

reading Baase Chapter 2.

Introduction

OCEAN

Privacy and the government

Nothing to Hide

NSA Surveillance

Parallel Construction

Microsoft

v US

Supreme Court Cases on Privacy

Third-party doctrine

Electronic Communications Privacy Act

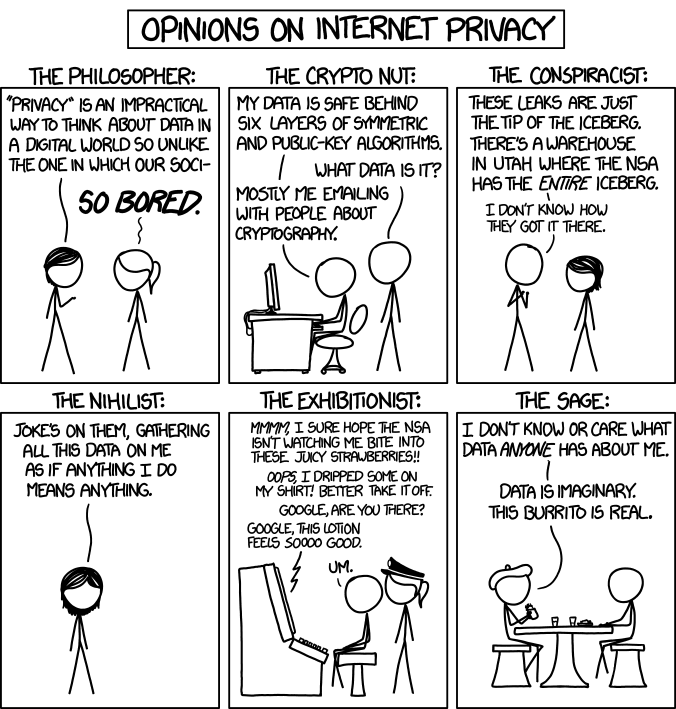

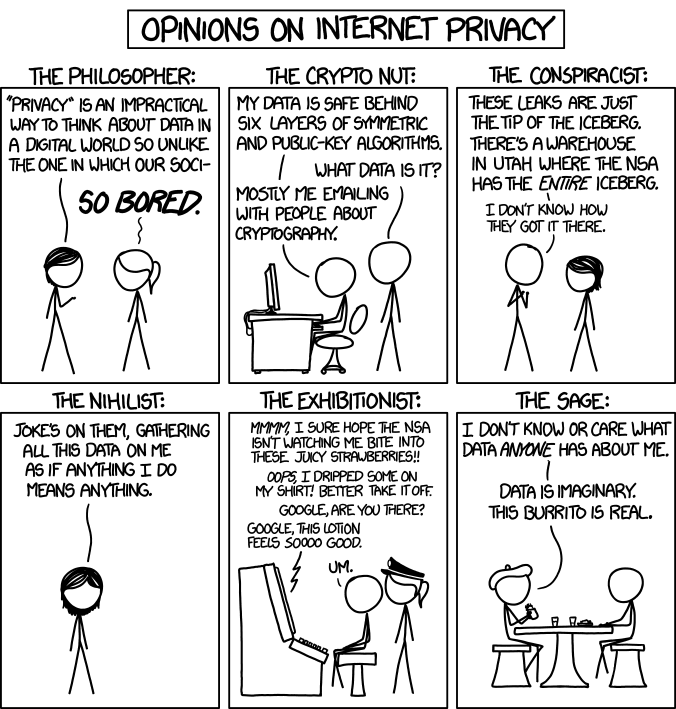

From xkcd.com:

http://imgs.xkcd.com/comics/privacy_opinions.png

They are watching you: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8JNFr_j6kdI.

The speaker is Jerry Day.

Is this a real threat? (See especially the section between 0:45 and 1:25)

I'm offering this as an example of a possible

threat, but which definitely has elements of "paranoia" as well. (I

imagine somewhere on YouTube there's a video of someone explaining the

dangers of the government eavesdropping on your conversations by beaming

lasers on your windows.)

That said, the organization Naperville

Smart Meter Awareness sued the city of Naperville, IL, starting in

2011. The city of Naperville is the utility for Naperville

residents, and they were collecting electrical-usage data every 15

minutes. The Seventh Circuit ruled that this data collection was in fact a

"search", but that in this particular case it didn't matter as the data

was not being used as evidence. See reason.com/volokh/2018/08/17/public-utilitys-recording-of-home-energy.

See also Jonas Diener.

And electric-meter data continues to be routinely subpoenaed by some

police departments. The police in Sacramento, CA do this, looking for

those cultivating marijuana, even though small-scale marijuana cultivation

is legal in California. (The police legal theory might be that residential

large-scale cultivators are simply avoiding taxes.) See reason.com/2025/07/23/sacramento-uses-smart-electric-meters-to-spy-on-residents.

The threshold for suspicious power use has dropped, and is now 2800

kWh/month. In July 2025 my home usage was 2046 kWh, mostly for air

conditioning.

Privacy

What is privacy all about? Baase (4e p 48 / 5e p 52) says it consists of

- control of information about oneself: who knows what about you?

- freedom from intrusion -- the right to be left alone in peace

- freedom from surveillance (watched, listened to, etc)

Are these all? Note that Baase put control of information as #2; I moved it

to #1.

In some sense the second one above is really a different category: the need

to get away from others. A technological issue here is the prevalence of

phones, blackberries, and computers and the difficulty of getting away from

work. (There is also a touch of class privilege here: lower-income people

have a much-diminished expectation of having access to any private space

(including the bathroom).)

The third one is to some degree a subset of the first: who gathers

information about us, and how is it shared? Another aspect of the third one

is freedom from governmental spying. Privacy from the

government is a major part of Civil Liberties. When we talk about government

surveillance, we often think of real-time surveillance: listening

in on our phone calls, tracking our location, or reading our emails.

However, a lot of government surveillance takes the form of retrospective

searches of databases gathered a while ago: checking what organizations we

belong to, where our car was seen a month ago, what purchases we made

recently, or what websites we visited.

Privacy is largely about our sense of control

of who knows what about us. We willingly put information onto Facebook, and

are alarmed only when someone reads it who we did not anticipate.

Privacy from:

- government

- commercial interests

- workplace

- local community (ie our friends and acquaintances)

What do we have to hide

Sometimes, when we try to argue for our privacy from the government, we get

asked what do you have to hide? See

below. (The internet-advertiser version of this is often

we're not collecting anything important).

On the one hand, many people who don't have anything to hide are nonetheless

uncomfortable with surveillance. On the other hand, a big part of post-9/11

surveillance (eg, what the NSA is doing) is for protection of the public.

On yet another hand, should we care at all about privacy? Or is it just

irrelevant?

MIT's Sherry Turkle gave the keynote talk at Loyola's Digital Ethics

conference in Fall 2012. She shared some comments made by teenagers in

privacy discussion groups:

- The way to deal with the loss of privacy is "just to be good"

- "Who would care about me and my little life" [respondent age 16]

Do we now have to be good all the time?

She also quotes Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg as saying "privacy is no

longer a relevant social norm".

Turkle's own rule for healthy democracies is that the government should

assume "everyone has something to hide". That way, there can be no arguing

that if you're in favor of greater privacy then you have "something to

hide". But what if safety is involved? Turkle's approach is especially

complicated when balancing a relatively large invasion of privacy against

a relatively low risk.

Strange history: once upon a time we were mostly concerned about privacy

from the government, not from private commercial interests. Then things

shifted 180°; commercial interests were the primary concern.

Now they have shifted 180° again.

Once upon a time, concern about privacy was on the decline. People knew

about the junk-mail lists that marketers kept, but it did not seem

important, especially to younger people.

In the last few years, commercial privacy has become a significant

issue. Why is this?

Personality

Psychologists have ways of defining general personality

traits, eg the OCEAN set of

- Openness (to new ideas and experiences)

- Conscientiousness

- Extraversion

- Agreeableness

- Neuroticism (tendency towards anxiety and worry)

(The Myers-Briggs system has four dimensions, and classifies you as at one

end or the other (eg extraverted or introverted) on each axis.)

We have reached the point that outsiders can create a psychological profile

of us using online data only. Once upon a time, the potential for this was

seen as frightening. But is it? Does it even matter if advertisers, or the

government, know we score relatively low on Conscientiousness?

Is this even what we mean by losing our privacy? Psychologists have

suggested that "getting to know someone" is based significantly on the slow

voluntary exchange of personal information, which would include our

personality traits.

Alternatively, maybe "losing our privacy" has meaning only when we have to

confront the loss in immediate social settings. Perhaps the marketing

information about us was too remote for us to be concerned. However, now

that Facebook has ushered in a new era of online information that is indeed

about our immediate social situation -- friends, events, likes -- maybe we

feel the loss of privacy much more keenly.

In 2010, Tal Yarkoni did a study Personality

and Blogging, in which he identified correlations between language use

and traditional OCEAN-based psychological categories, using subjects who had

consented to a standard psychological-profile evaluation. He was able to

create a mechanism for determining someone's psychological categorization

just from the language the person used in blogging.

In 2013, IBM's Eben Haber extended this to (much-shorter) twitter postings.

The goal is indeed to make use of the inferred information about personality

to target marketing efforts more effectively. The original (short) paper is

PersonalityViz:

A Visualization Tool to Analyze People's Personality with Social Media,

by Liang Gou, Jalal Mahmud, Eben M. Haber and Michelle X. Zhou. See also http://www.economist.com/news/science-and-technology/21578357-plan-assess-peoples-personal-characteristics-their-twitter-streams-no.

An important corollary of Yarkoni and Haber's work is that it appears to be

much harder to conceal ones fundamental personality when online than some

have perhaps thought.

In January 2015, Youyou, Kosinski and Stillwell published a paper in which

they showed that Facebook likes also revealed ones OCEAN profile, and

furthermore did this more accurately than family and friends: Computer-based

personality judgments are more accurate than those made by humans.

This research has been widely covered in the popular press: see news.stanford.edu/news/2015/august/social-media-kosinski-082515.html,

where coauthor Kosinski notes "one of our most surprising findings is

that we could even predict whether your parents were divorced or

not, based on your Facebook likes." You can also go to http://applymagicsauce.com/

where you can upload your Facebook likes and then click "predict my

profile".

And then there are all those Facebook quizzes. Many of these represent

someone very deliberately mining for information about your OCEAN profile,

to help determine the kinds of ads you'll see. This works even if Facebook

keeps all the results: an advertiser can say "show this ad to

everyone whose best-match dog breed is a pit bull and whose best-match

flower is a thistle". See www.nytimes.com/2016/11/20/opinion/the-secret-agenda-of-a-facebook-quiz.html.

Personality identification in the advertising world continues to grow more

and more precise. Ordinary advertisers often have access to this

information; Facebook has your personality down very precisely. Do

you care? Yes, it can be used to help target ads to you, but only

in conjunction with other information about your interests.

Personalization

We understand that all sorts of online purchasing information is collected

about us in order for the stores to sell to us again. Whenever I go to

Amazon.com, I am greeted with book suggestions based on past purchases. But

at what point does this information cross the line to become "personalized

pitches"?

What if the seller has determined that we are in the category

"price-sensitive shopper", and they then call/mail/email us with pitches

that offer us the "best price" or "best value"? (See the box on Baase, 4e p

72 / 5e p 65, for a related example. Here, the British Tesco

chain determined which shoppers were "price-conscious", and also what they

were most likely to buy. These products (maybe the top 20 in sales volume?)

were then priced below Wal*Mart's prices.)

Political parties do this kind of personalization all the time: they tailor

their pre-election canvassing to bring up what they believe are the

hot-button issues for you personally.

Marketing personalization sometimes involves your personality profile, but

often weighs other attributes (like "price-sensitive shopper) more highly.

What do computers have to do with

privacy?

Old reason: they make it possible to store (and share) so much more data

Newer reasons:

- They enable complex data mining

- They allow us to find info on others via Google

- Records are kept that we never suspected (eg Google searches)

- Electronic eavesdropping

Baase, 4e p 48 / 5e p 52: The communist East-German secret police Stasi were

masters of non-computerized privacy invasion. The film The

Lives of Others was about this.

The Fourth Amendment states:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses,

papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures,

shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon

probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly

describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be

seized.

Note that "unreasonable" and "search" are both unclear, and the "persons,

houses, papers and effects" part is only marginally clearer. For example,

does this list include ones online information?

Note the requirement that the person and place be specifically described.

Does this rule out broad online searches? (See "geofence" warrants,

below.)

The Federal warrant form is at www.uscourts.gov/sites/default/files/ao093.pdf.

Baase 4e p 50 / 5e p 54: many companies use computers to create "a detailed

picture of the person's interests, opinions, relationships, habits and

activities".

Maybe also of what sales pitches we're likely to respond to?

Some non-governmental privacy issues:

- shopping data

- RFID chips in cards and merchandise

- search-engine queries

- cellphone GPS data

- event data recorders in automobiles

Caller ID

When it first came out in the early 1990's, Caller ID was widely seen as a

privacy intrusion. That is, it

took away your "right" to call someone anonymously. Actually, that is

a plausible right if you're calling a commercial enterprise; if you don't

want them calling you back, you should be able to refuse to give them your

number.

Within a decade, Caller ID was widely seen as a privacy boost: you could

control who could interrupt you. This is privacy in sense #2 above; the

original issue was privacy in sense #1.

Caller ID never caught on with stores; it did

catch on with ordinary people.

Is there any right to phone someone

anonymously? What if you're trying to give the police a tip? What if you're

a parole officer?

Maybe some of the most sensitive information gathered about us today is our

location, typically from a cellphone. Traditional phones do not necessarily

track GPS in real time, unless an emergency call is placed, but smartphones

do this continuously in order to display advertisements for nearby

businesses. What undesirable things could be done with this information?

We will return to this later.

http://pleaserobme.com, listing

twitter/foursquare announcements that you will not be At Home (now "off"; I

wish I'd kept some sample data)

Facebook has made us our own worst privacy leakers.

Facebook and college admissions, employment, any mixed recreational &

professional use

Here is a list of some specific things we may want to keep private, and

which might also appear in records somewhere:

- past lives (jobs, relationships, arrests, ...)

- life setbacks

- medical histories

- mental health histories, including counseling

- support groups we attend

- organizations of which we are members

- finances

- legal problems (certainly criminal, and often civil too)

- alcohol/drug use

- tobacco or alcohol purchases

- most sexual matters, licit or not

- whether we've had an abortion

- ones Tinder history

- pornography preferences

- pregnancy-test purchases; contraceptive purchases

- private digressions from public facade

- different facades in different settings [friends, work, church]

- comments we make to friends in context

- what about Donald Sterling, former owner of the LA Clippers? (A

partial transcript of his infamous call is here.)

- the fact that we went to the bar twice last week

- the fact that we did not go

to the gym at all last week

- minor transgressions (tax deductions, speeding, etc)

Of course, a central issue in the last item is what constitutes "minor".

In keeping these sorts of things private, are

we hiding something?

More significantly, what has the rise of Facebook done to this list? How

much do we care about this "general background" information as opposed to

the kind of information that leaks out of Facebook: who we partied with last

night, what we drank, who we partied with five years ago, where we were last

night given that we said we would

be volunteering at the soup kitchen?

Consider the item above about "different facades in different settings". In

this context the following quote from Mark Zuckerberg is relevant:

The days of you having a different image for

your work friends or co-workers and for the other people you know are

probably coming to an end pretty quickly. ... Having two

identities for yourself is an example of a lack of integrity"

[from David Kirkpatrick, The Facebook Effect]

Lack of integrity? Really? The only thing that keeps LinkedIn alive is

that most people believe in keeping at least some separation between their

work life and pictures of their partying. But the separation goes much

deeper than that; many people maintain different images in different

contexts. See also michaelzimmer.org/2010/05/14/facebooks-zuckerberg-having-two-identities-for-yourself-is-an-example-of-a-lack-of-integrity.

In Japan, there are terms for ones "true feelings" and ones "public

opinions": honne and tatemae (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Honne_and_tatemae).

Divergence between the two is widely accepted, and is not regarded as

"hypocrisy".

Sometimes we want to keep things private simply to avoid having someone else

misinterpret them.

Is this list what is really important to us in terms of privacy? Or are we

really only concerned with more intangible attributes?

In 1979, Harold Sackeim and Ruben Gur studied self-deception. They asked

participants the questions below, with the understanding that the honest

answer was almost always "yes" (this is debatable, but they do have a

point). The number of "no" answers was then interpreted as an indication of

self-deception.

For our purposes, the issue is that these questions represent another list

of things we might very well wish to keep private (note that the

survey dates from 1979, when taboos against homosexuality were still

strong).

1. Have you ever felt hatred toward either of

your parents?

2. Do you ever feel guilty?

3. Does every attractive person of the opposite sex turn you on?

4. Have you ever felt like you wanted to kill somebody?

5. Do you ever get angry?

6. Do you ever have thoughts that you don't want other people to know that

you have?

7. Do you ever feel attracted to people of the same sex?

8. Have you ever made a fool of yourself?

9. Are there things in your life that make you feel unhappy?

10. Is it important to you that other people think highly of you?

11. Would you like to know what other people think of you?

12. Were your parents ever mean to you?

13. Do you have any bad memories?

14. Have you ever thought that your parents hated you?

15. Do you have sexual fantasies?

16. Have you ever been uncertain as to whether or not you are homosexual?

17. Have you ever doubted your sexual adequacy?

18. Have you ever enjoyed your bowel movements?

19. Have you ever wanted to rape or be raped by someone?

20. Have you ever thought of committing suicide in order to get back at

someone?

For many of these, however, there are not any records (except for

#8, if your friends' cameras were handy at the time).

Some data collection that we might not even be aware of:

- browser-search data from Google

- browser location data

- ISPs and browser-search data

- web cookies

- automobile event recorders

Event data recorders in cars: lots of cars have them.

Starting around 2010, many such systems connect wirelessly

to the manufacturer, transmitting data including location

- fresh-values / preferred card

LOTS of people are uneasy about privacy issues

here, but specific issues are hard to point to.

Until 2010, my local Jewel never asked for

Preferred cards for alcohol sales.

Then they started again, but shortly after they

discontinued the card for everything.

- street-level car cameras

- street-level pedestrian cameras

- bookstore purchases

- library records

- Tinder history

- RFID data

Where do we draw the line? Or is there no line? Is loss of privacy a matter

of "death by a thousand cuts"?

Privacy from the government

This tends not to be quite as much a computing issue, though

facial recognition might be an exception. "Matching" (linking the names,

say, of everyone receiving welfare payments and also owning a car worth more

than $15K) was an example once upon a time. Interception of electronic

communications generally fits into this category; the government has tried

hard to make sure that new modes of communication do not receive the same

protections as older modes. They have not been entirely successful.

One of the biggest issues with government data collection is whether the

government can collect data on everyone, or whether they must have some

degree of "probable cause" to begin data collection. On 4e p 69 / 5e p 87 of

Baase there is a paragraph about how the California Department of

Transportation photographed vehicles in a certain area and then looked up

the registered owners and asked them to participate in a survey on highway

development in that area.

Why might that have been considered to be a problem?

The California episode probably happened in the late 1990's. Does that

matter?

Police departments (and their civilian contractors) across the US are now

routinely scanning all license-plate numbers.

Canadian position: government must have a "demonstrable need for each piece

of personal information collected".

Nothing to Hide

Why do we care about privacy? Is it true that we would not care if we had

nothing to hide? What about those "minor transgressions" on

the list? Are they really minor?

Or is is true that, as Julian Sanchez wrote, "we live 'in a nation whose

reams of regulations make almost everyone guilty of some violation at some

point'" [Baase 4e p 63 / 5e p 84]

The "nothing to hide" question is central to privacy. But note the hidden

assumption that you only need privacy if you do have something to

hide!

Once upon a time (in the 1970's) there was some social (and judicial)

consensus that private marijuana use was modestly protected: police had to

have some specific evidence that you were lighting up, before they could

investigate. Now, police are much more free to use aggressive tactics (eg

drug-sniffing dogs without a warrant, though they can't use thermal imaging

without a warrant).

Is this a privacy issue?

Now the NSA collects everyone's phone records, and sometimes (it is not

entirely clear how often) uses the information to identify drug dealers

(including marijuana dealers). The information may then be turned over to

the DEA.

Is personal marijuana use an example of the kind of thing we have a "right"

to keep hidden from the government? Or should the government make use of

every possible tool to prevent this?

What about speeding?

What about claiming as a tax deduction a lunch with a colleague, during

which you supposedly discussed business, but your pre-lunch texts to one

another make it clear that you both really wanted to discuss a soccer

match?

Perhaps "you should have nothing to hide" is a bit harsh. Maybe another

way to phrase this is to say that, in the interests of preventing

terrorism, child abuse, narcotics trafficking, organized crime and

cybercrime, we should all cooperate to give law enforcement better access.

What things might someone want to keep secret from the government?

Here are a few "Nothing to Hide" essays:

There is also Daniel Solove's paper "'I've got nothing to hide', and

other misunderstandings of privacy", papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=998565.

Do you believe these arguments?

A more specific argument is the basis of Harvey Silverglate's book "Three

Felonies A Day: How the Feds Target the Innocent". Unfortunately, many of

Silverglate's examples relate to disclosure or non-disclosure or

corporate-malfeasance issues that are very complicated. However, back

(last year) when violating any of Loyola's computer policies was a felony,

I might have had that issue. (For example, Loyola's policies required that

servers only be used in server rooms, accessible only to ITS employees,

and also that every laptop was a server (because svchost

processes are servers!).)

How about end-to-end encryption of messages? That's a very specific

thing that governments would like to put a stop to. Should we help them?

What are some justifications for choosing end-to-end encryption of our

messages?

The post-9/11 loss of American privacy to government surveillance was

often justified by "if you have nothing to hide, you have nothing to

fear". Ironically, the strongest proponents of this approach were on the

political right, who are -- in 2021 -- rather obsessed with "personal

freedom" and the right not to wear a mask.

A much more specific version of the "nothing to hide" argument is that

having the NSA collect your phone metadata is a small price to pay for

greater American safety in a post-9/11 world. Does your phone metadata

implicate you in any way? (It might if you are leaking government secrets,

or if you are in an illicit relationship.)

"Everyone is guilty of something or has

something to conceal. All one has to do is look hard enough to find what

it is" -- Alexandr Solzhenitsyn (the opinion of the character Rusanov -- a

records manager -- in Cancer Ward)

There is also another approach to the "what do you have to hide"

question: do you trust the government? You might feel you have

something to "hide" if you do not. But consider:

- Did you trust the Obama administration?

- Did you trust the Trump administration?

It is not unreasonable to suppose that only those who trusted both

might be comfortable with intrusive government surveillance.

Maybe we should trust the government more, or at least trust

law enforcement. But many do not.

There is also the issue of self-censorship; see the IETF

document below. When subjected to continued surveillance, even if

not very intensive, people often have a tendency to speak and act with

greater restraint. One might be less likely to attend a protest march, for

example, or to criticize the government in emails. Messages and emails

might be less likely to express sentiments that disagree with the

authorities. There is an incentive to conform. For this to happen, one

must, of course, be aware of the surveillance.

You can be very confident you have nothing to hide, nothing to worry

about, but still be aware that getting on the No-Fly List would be

personally catastrophic.

What is Privacy For?

Closely related to the "nothing to hide" approach is the question of just

what privacy is for, socially. Most societies do have strong

norms about privacy: some conversations are hushed, for example, when a

third party approaches. What is all that about? Is privacy an important

social element? Why should we be concerned about what information we share

with others? One possibility is that, without privacy, we cannot define

our more intimate relationships in terms of sharing additional personal

information, because everyone knows everything. Or might the roots of

privacy lie in keeping food resources secret?

Sometimes privacy is about, as Judge Richard Posner wrote, the

right of a person "to conceal discreditable facts about himself". But

privacy clearly goes beyond simply trying to conceal ones past

misbehavior.

We do keep passwords private; is that a special case, or is

that really a part of privacy? It is one thing to keep our bank password

private to prevent others from taking our money, but should we

object to others simply knowing how we spend our money?

We also live in spaces with walls, and have curtains on our windows. It

is sometimes suggested that sexual privacy is related to relationships

that may lack social approval -- and so must be kept private. However,

even modest hints of a sexual relationship (eg public displays of

affection) often make observers quite uncomfortable.

Sometimes people hold opinions that are contrary to the opinions of those

in power, and so keeping those opinions private may be a matter of

personal safety.

Privacy is often associated with autonomy and independence; most people

value the latter two quite strongly. To lose privacy is also to lose

social position; to put it another way, privacy is correlated with social

rank. And in essentially all societies, people are very concerned about

their social rank. In modern terms, loss of privacy due to government

surveillance is indeed associated with feelings of helplessness and

powerlessness (though the NSA tried to keep its phone-metadata program

very secret). But it is also true that people use privacy to conceal past

misbehaviors, and to that extent the purpose of privacy is to

manipulate ones social rank so it is higher than it would be otherwise.

Perhaps you have some minor things to hide. Traditionally, that was the

justification for the Fourth Amendment. But how does that change in a world

with mass terrorist attacks? Some in the NSA have argued that as soon as

there is another attack, everyone will be clamoring for more

surveillance.

How much surveillance do we need? How much do we want?

On 4e p 50 / 5e p 54, Baase quotes Edward J Bloustein as saying that a

person who is deprived of privacy is "deprived of his individuality and

human dignity". Dignity? maybe. But what about individuality? Is there some

truth here? Or is this overblown?

On 4e p 62 / 5e p 78, Baase quotes Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas

as saying, in 1968,

In a sense a person is defined by the checks

he writes. By examining them agents get to know his doctors, lawyers,

creditors, political allies, social connections, religious affiliation,

educational interests, the papers and magazines he reads, and so on ad

infinitum.

Nowadays we would add credit-card records. Is Douglas's position true?

The NSA and the Snowden Leaks

In the aftermath of the September 11, 2001 attack on the World Trade Center,

Congress passed the USA Patriot Act (or Usap At Riot Act, as Richard

Stallman likes to call it). Title II of this act greatly expanded the powers

of federal agencies to conduct surveillance on suspected terrorists.

Congress created the Foreign Intelligence Surveilllance Courts (or FISA

Courts) with the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978. These courts

gained additional authority with the Patriot Act. The FISA courts were

charged with issuing any necessary warrants for surveillance under the

Patriot Act.

The NSA eventually began collecting all of the following:

- Telephone records of essentially every call placed in the US

- contents of emails, Facebook messages, SMS messages and other

text-based communications

- raw packet data from direct taps into central Internet routers

The NSA claimed that all this was authorized by §215 of the Patriot Act,

which allows collection of a wide range of records for investigations

involving international terrorism. The pre-9/11 §215 allowed for

collection of "business records"; this was amended to allow collection of

"any tangible thing". The NSA interpreted this to allow collection of data

on US nationals as long as the investigation involved someone

who was not a US national. Here is the text of the relevant portion of the

act:

ACCESS TO CERTAIN BUSINESS RECORDS FOR FOREIGN

INTELLIGENCE AND INTERNATIONAL TERRORISM INVESTIGATIONS.

(a)(1) The Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation or a designee

of the Director (whose rank shall be no lower than Assistant Special Agent

in Charge) may make an application for an order requiring the production

of any tangible things (including books, records, papers,

documents, and other items) for an investigation to protect

against international terrorism or clandestine intelligence activities,

provided that such investigation of a United States person is not

conducted solely upon the basis of activities protected by the first

amendment to the Constitution. [pld: does this provision mean

anything?]

(2) .. (b) Each application under this section--

(1) shall be made to--

(A) a judge of the court established by section 103(a);

or [pld: this is the FISA court]

(B) a United States Magistrate Judge under chapter 43 of title 28,

United States Code, ...

(2) shall specify that the records concerned are sought for an

authorized investigation conducted in accordance with subsection (a)(2) to

protect against international terrorism or clandestine intelligence

activities.

...

(d) No person shall disclose to any other person

(other than those persons necessary to produce the tangible things under

this section) that the Federal Bureau of Investigation has sought or

obtained tangible things under this section.

That the FISA courts are authorized to hear these cases is explicit in

(2)(1)(A). That is, the law clearly provides for the FISA courts to

authorize release of records of US nationals (the original jurisdiction of

the FISA courts was limited to non-US-nationals). The law also makes clear

that records can be released as part of any investigation;

the person whose records are released does not have to be a

subject of that investigation. That is, your records can be

released as part of an investigation of someone else.

The last clause quoted here, (d) mandates that communications providers

can not reveal to the public or their customers anything about this

surveillance activity. These "gag orders" are unpopular with providers.

They undermine confidence in the US software-services industry. The reason

nobody had any idea about the extent of NSA domestic surveillance before

Snowden was that these gag orders prevented talking about it. See below.

In May 2013, Edward Snowden began releasing internal, classified information

about the National Security Agency's domestic-spying program. The

information was published starting in June 2013 by the Washington Post and

the British newspaper The Guardian. While there are lots of spying events

documented by Snowden, the two primary ones are the sweep of telephone

records and the PRISM program involving the content of emails.

In May 2006, the FISC issued its first order (a mass subpoena) requiring

telephone providers to turn over all telephone records to

the NSA, as part of the PRISM program. These records

include:

- number called

- number placing the call

- subscriber information

- length of call

- location of any mobile phones involved

The content of the call is not saved. The records above are the

normal business records of the providers. The government has long considered

"normal business records" to be fair game, although others have objected to

this interpretation. The Supreme Court ruled in Smith v Maryland

that the police do not need a warrant to gather the called-number

information for phone calls. But is your cellphone's location a "normal

business record"?

Note that there is no claim by the government that any particular phone

number might be associated with illegal activity.

The original order allowed for the collection of the data, but any use

had to be approved by the FISC. In 2009 the FISC discovered that the NSA had

not been complying with this portion of the requirement. Exactly what is the

status of the regulations on the use of this data is not clear.

The PRISM program also involved the collection of contents

of email and other text-based messages (and possibly some Skype calls). This

data came from providers (eg Gmail, Yahoo and Microsoft). The third leg of

the program included data obtained through direct taps into key Internet

routers. This information was supposedly collected on a per-name (that is,

individual) basis, but emails were included of those who were on the third

"hop" away from a suspect (someone who corresponded with a suspect is on the

second hop). So communications between US nationals were definitely

included.

Supposedly no warrant is needed to monitor communications of either

non-nationals or of US nationals traveling outside the US. However, the

FISA court generally signed off on the subpoenas involved. Mass

surveillance is impractical if "probable cause" must be established for

every individual involved, eg for a warrant.

Ten years after the Snowden revelations, the IETF published an Internet

Draft, www.ietf.org/id/draft-farrell-tenyearsafter-00.html,

discussing the consequences of Snowden, and some subsequent developments.

One theory is that warrants are not easy to get, and the relatively

lopsided success rate (over 99%) is due to careful preparations by the

police for each and every one. There is in fact some evidence that FISA

court warrant applications often receive a reasonable degree of care.

Still, there is never anyone involved whose role is to speak against

the warrant.

In December 2019 Justice Department's Inspector General released a report

about FISA warrants, in particular related to the investigation of Carter

Page, a Trump associate. The New York Times published an article: nytimes.com/2019/12/11/us/politics/fisa-surveillance-fbi.html.

Generally, FBI agents did not present evidence contrary to the

theory that Page was in cahoots with the Russians.

Snowden claimed he tried to bring his legal issues with mass

surveillance to the attention of his superiors at the NSA. The NSA denied

this. A 2016 article suggested that the NSA was not being truthful: https://news.vice.com/article/edward-snowden-leaks-tried-to-tell-nsa-about-surveillance-concerns-exclusive.

However, neither did Snowden present detailed descriptions of his attempts

at contacting his superiors.

Denmark

The US is not the only country to engage in broad surveillance. Denmark

offers extensive social-welfare benefits, spending a remarkable 26% of

budget on this. Some Danes have become very concerned that these benefits

are not going to those who are not entitled to them. To this end, the

Danish government has created a group within the Public Benefits

Administration to root out cheaters, using surveillance techniques. See www.wired.com/story/algorithms-welfare-state-politics.

The anti-fraud group cross-checks multiple government databases,

looking, for example, for benefit recipients who are employed, or who

travel frequently, or who own cars. Such matching has become routine in

the US as well. The group has also considered checking electric and water

bills to see if recipients were actually living at the addresses they

listed. The system does track relatives in other countries, both in the EU

and outside.

There is particular concern that someone receiving benefits might in

fact be living with a partner who does not qualify. To detect this,

nearest-tower cellphone location data has been used to determine where

someone is sleeping. Child registries are also used to identify the other

parent of any of a recipient's children, to see if the benefit recipient

is living with that other parent. Credit-card records are checked, to see,

for example, if there are regular gas and food purchases near ones claimed

home address. And there are in-person surprise visits, though those are

expensive. There are claims that recipient's social-media histories have

been searched for this purpose.

See also www.dr.dk/nyheder/indland/kommuner-vil-gaa-endnu-laengere-fange-sociale-bedragere

(in Danish, but Google Translate does a fair job).

The Danish system is supposed to allow a hearing for everyone accused.

Apparently these hearings impose penalties on only 8% of those flagged,

suggesting that 92% had done nothing wrong.

A similar system in the Netherlands falsely flagged

thousands of families for welfare fraud in 2021. It eventually turned out

that the algorithm used national origin inappropriately; the people

flagged were mostly recent immigrants.

Encryption

If your interaction with Facebook or gmail was via https,

that is, via an encrypted web connection, then the NSA would have to decrypt

anything it obtained through router taps. Decryption of much https traffic

is not terribly difficult, but it is time-consuming, and the NSA

probably cannot afford to decrypt all of it. Obtaining message information

from the providers -- such as Facebook and Google -- avoids that.

You can encrypt your email on an end-to-end basis, but that is not

exactly trivial. The standard open-source public-key encryption package is

probably GPG (Gnu Privacy Guard). There is a plugin for the Thunderbird

email reader, known as enigmail, that provides email

support for GPG. That is, email messages to and from selected recipients are

automatically encrypted and decrypted.

Catch #1: You have to resolve the public-key-trust issue.

Suppose Alice wants to email Bob, with whom she has no pre-existing

relationship. Then Alice needs Bob's public key. She can just

trust that the key is the one on Bob's website, but what if the NSA

redirects Alice to a fake copy of Bob's site, with a fake public key? Alice

then sends the email encrypted with the NSA's public key. The NSA decrypts

it, saves it, and re-encrypts it with Bob's real public key and delivers it

to Bob. Bob is none the wiser.

This is known as the "man-in-the-middle" attack.

The traditional assumption here is that you get other people's public keys

from people you trust. This can be tricky.

The Signal encrypted-text-message system has a reasonably convenient

approach to this problem. If Alice is worried, she can call Bob

(the idea is that she would recognize Bob's voice) and the two can exchange

key "fingerprints" by voice.

Catch #2: How many other people will set up encryption?

Until there is a large number, Alice's email stands out by dint of being

encrypted. The NSA can devote intense resources to breaking the encryption.

And Alice is now on the Watch List.

Also, you can only use encryption with other people who have set it up. Most

of your email is thus likely to remain plaintext.

Signal has tried hard to make encryption universal. Their biggest success

was probably in convincing Whatsapp to use their TextSecure protocol.

Catch #3: Where do Alice and Bob keep their keys? If they

are on their respective computers permanently, then they are vulnerable. If

they are only entered when necessary, then the act of typing the key is a

weak point. If Alice and Bob want to get each others' email on the go, and

try to use encryption on their smartphones, that becomes a weak point.

Parallel Construction

On the one hand, national security is an important goal. But what about the

following two-step argument:

- The government will intercept all emails and phone records in order to

improve national security

- Since we have all these emails, we will also use them to track down

those selling illegal drugs, those engaged in bank fraud, and those

claiming excess deductions on their tax returns

There have been repeated claims that the Special Operations Division of the

DEA has been beneficiary of some NSA data, and has been using it in

narcotics arrests. DEA agents, according to this theory, have been trained

in the art of parallel construction -- coming up

with an alternative explanation for why someone was arrested, that avoids

disclosure of the NSA data. While to a point this is legitimate, ultimately

the defendant's right to a fair trial depends on obtaining all

information about how a case was investigated.

More disturbingly, use of personal data obtained without a warrant is

often forbidden at trials. If the NSA/DEA subterfuge here acually

occurred, then it intentionally bypasses that. The NSA has also shared

information with other federal agencies, including the IRS.

The effect of all this is would be to allow the use of NSA-collected data in

ordinary criminal prosecutions.

See the article at http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/08/05/us-dea-sod-idUSBRE97409R20130805.

However, the facts here are difficult to verify, so we don't really know the

extent to which parallel construction was used. The DEA apparently does

benefit from parallel construction, often to protect informants. The part

that is not clear is the extent to which the NSA dragnet has been the

source.

A more recent, better-documented example [2014] is described in theintercept.com/2016/05/05/fbi-told-cops-to-recreate-evidence-from-secret-cell-phone-trackers.

A memo regarding the use of the Stingray cellphone tracker was sent to the

Oklahoma City police department by FBI agent James Finch. It reads, in part:

Information obtained through the use of the

equipment is FOR LEAD PURPOSES ONLY, and may not be used as primary

evidence in any affidavits, hearings or trials. This equipment provides

general location information about a cellular device, and your agency

understands it is required to use additional and independent investigative

means and methods, such as historical cellular analysis, that would be

admissible at trial to corroborate information concerning the location of

the target obtained through the use of this equipment.

The problem here is that it is illegal for police to withhold evidence, but

it is hard to read this paragraph as not advocating just that! If historical

cellular data is adequate, why do the police need a Stingray? The real

problem with historical cellular data is that the police use the Stingray to

identify the suspect; finding the applicable historical data is like looking

for a needle in a haystack.

In the last century, the federal government discouraged encryption with the

stated goal of being able to investigate the following groups:

- terrorists

- child pornographers

- narcotics traffickers

What happens when the third group above includes recreational (or

medical) marijuana users? For that matter, what if the first group is

taken to include anyone who expresses an interest in a "subversive"

organization, such as Occupy Wall Street?

In 2016, the FBI petitioned Congress for access to a basic form of browser

records: a list of what web IP addresses you connected to. The FBI has tried

to argue that this was left out "by mistake" from a much earlier version of

the law, but that law explicitly listed only telephone records. See https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/fbi-wants-access-to-internet-browser-history-without-a-warrant-in-terrorism-and-spy-cases/2016/06/06/2d257328-2c0d-11e6-9de3-6e6e7a14000c_story.html.

Is a telephone call record really like a website connection? The phone

company uses the former for billing (or used to); no ISP uses your website

connections for billing. In this sense they are not business records.

In 2008, Yahoo attempted to fight the PRISM-based FISA Court order to turn

over a large volume of emails. The case made it to the appellate level --

the US Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court of Review. The partially

redacted decision -- at http://www.fas.org/irp/agency/doj/fisa/fiscr082208.pdf

-- is chilling. First off, the appeals court makes several references to the

trial court decision, but the trial court decision is secret. The

trial-court decision is referred to as "Sealed Case".

Yahoo raised two issues: that a warrant was always needed, even for foreign

nationals, and that the requests for information were "unreasonable".

The first point -- whether the fourth amendment applies to foreigners -- is

a serious issue, but the court dismissed it without considering precedent.

As for the second point, the court basically agreed that there should be no

clear line "between foreign intelligence purposes and criminal investigation

purposes". Of course, some might argue that this should raise the

bar for whether a search was "reasonable", but the FISC ruled that as long

as the stated purpose was foreign-intelligence gathering, then

subpoenas were ok. The FISC turned the Fourth Amendment on its head by then

arguing (p 17) that warrants were "unreasonable":

We add, moreover, that there is a high

degree of probability that requiring a warrant would hinder the

government's ability to collect time-sensitive information and,

thus, would impede the vital national security interests that are at

stake.

Finally, the court decided that whether a search was "reasonable" must

depend on its importance. If national security is at stake, essentially all

searches (according to the opinion) become reasonable.

At one point (page 12) the decision states, in case the reader is confused,

"This makes perfect sense".

Spying and harm

Does the NSA spying on Americans actually cause any harm to ordinary

Americans? Is it true that if we have nothing to hide, then we have nothing

to fear?

The government has long kept tabs on those who participate in protest

movements. So what?

Is there a "chilling effect"? If so, is it strong enough to matter?

According to a Congressional investigation committee, "Martin Luther King,

Jr. was the target of an intensive campaign by the Federal Bureau of

Investigation to 'neutralize' him as an effective civil rights leader." What

could the FBI actually do to MLK? They tried exposing him as a communist,

but failed as MLK had no ties to communism.

In November 1964 the FBI sent King an anonymous letter, here,

in which the letter writer threatens to expose King as a fraud (possibly for

adultery) and suggests that the only way out is for him to commit suicide.

Alternatively, perhaps the government might have tried blackmailing King.

Is this concern of any large-scale significance?

How is this related to apparent NSA use of sexual information to discredit

what it calls "radicalizers"?

The National Security Agency has been

gathering records of online sexual activity and evidence of visits to

pornographic websites as part of a proposed plan to harm the reputations

of those whom the agency believes are radicalizing others through

incendiary speeches, according to a top-secret NSA document. The document,

provided by NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden, identifies six targets, all

Muslims, as 'exemplars' of how 'personal vulnerabilities' can be learned

through electronic surveillance, and then exploited to undermine a

target's credibility, reputation and authority.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/11/26/nsa-porn-muslims_n_4346128.html

Is this the basis for another argument that we are entitled to privacy even

if we have "nothing to hide"? On the other hand, this case is 60 years ago,

and King did not commit suicide.

Do we agree to this?

James Clapper, director of the NSA, says "We Should've Come Clean About

Phone Surveillance": http://swampland.time.com/2014/02/17/james-clapper-nsa-phone-surveillance/

I probably shouldn't say this, but I will...

Had we been transparent about this from the outset right after 9/11 --

which is the genesis of the 215 [Section of the Patriot Act -- pld]

program -- and said both to the American people and to their elected

representatives, we need to cover this gap, we need to make sure this

never happens to us again, so here is what we are going to set up, here is

how it's going to work, and why we have to do it, and here are the

safeguards ... We wouldn't have had the problem we had.... If the program

had been publicly introduced in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, most

Americans would probably have supported it.

Never mind that in June 2013 when the phone surveillance first came to

light he was quite upset that the secrecy of the program was lost. Now

that our enemies knew about it, he said then, they would find other ways

to communicate.

In the post-9/11 context, do you support at least the basic framework of

the NSA surveillance? Do you think a majority of Americans do? There may

have been some excesses (such as hacking and "parallel construction"), but

ignore those for the moment.

Smart cities

Some cities are trying to become "smart cities", leveraging information

technology to become better places to live. Here's an article about

Toronto: www.cbc.ca/news/technology/smart-cities-privacy-data-personal-information-sidewalk-1.4488145.

Sensors collect information about car usage, bike usage, pedestrian usage,

and trash-can usage.

This might lead to better traffic flow, but at what privacy cost? Nobody

knows.

ACLU v Clapper

On May 7, 2015, the Second Circuit released their

decision in ACLU v Clapper, in which they found that Section 215 of the

Patriot Act does not allow bulk phone-metadata

collection. Implementation of the ruling was stayed, however, pending

appeal to the Supreme Court.

The decision did not address whether such collection violates the Fourth

Amendment; the claim was simply that the existing Section 215 did not allow

for the data collection that was being done.

The opening of the argument raised issues of domestic FBI surveillance

during the 1970's, which was eventually significantly curtailed.

The court also pointed out

A call to a single-purpose telephone number

such as a "hotline" might reveal that an individual is: a victim of

domestic violence or rape; a veteran; suffering from an addiction of one

type or another; contemplating suicide; or reporting a crime. Metadata can

reveal civil, political, or religious affiliations; they can also reveal

an individual's social status, or whether and when he or she is involved

in intimate relationships.

A large part of the case hinged on whether the ACLU, together with a set of

telephone subscribers, had in fact standing to sue. The Second Circuit held

that they did, because the government had collected their phone records.

Actual use of the records did not have to be shown, let alone actual harm.

On June 1, 2015, section 215 of the Patriot Act expired,

along with a few other provisions.

The next day Congress passed (and the president signed) the

so-called Freedom Act, which granted a 6-month extension to the NSA's

phone-metadata-collection program. After that time, the data-collection

program apparently came to an end.

On June 29, 2015 the FISA Court of Appeals ruled that the

Freedom Act had implicitly authorized the continuation of the NSA's

metadata-collection program, at least for 6 months, and thus "reversed" the

Second Circuit. The reversal of the Second Circuit decision raises a

decidedly awkward question of jurisdiction, but the FISA court has a point,

and the Second Circuit had stayed their own order pending appeal.

But because of the ending of the bulk-data-collection program, the case was

not appealed to the Supreme Court.

Microsoft vs US

(This case is also known as the "Microsoft Ireland case", and is not to be

confused with the antitrust litigation US v Microsoft.)

In December 2013, Microsoft received a search warrant from the US Department

of Justice for the email of a drug-trafficking suspect. Microsoft refused,

on the legal theory that the data was stored at a data center in Ireland,

and that therefore Irish laws should apply. The DoJ, instead of obtaining

approval of Irish authorities, decided that Microsoft had to turn over the

data because it was a US company, no matter where the data was located.

One problem with the government's legal theory is that it may be illegal

in the remote jurisdiction to turn over documents without a warrant.

See bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-09-02/as-microsoft-takes-on-the-feds-apple-and-amazon-watch-nervously

and also natlawreview.com/article/microsoft-ireland-case-status-and-what-s-to-come.

Microsoft appealed to the Second Circuit. In July 2016 a three-judge panel

ruled unanimously in Microsoft's favor: the US must obtain a warrant in

Ireland, under the existing mutual-legal-assistance treaty. The US asked for

an en banc rehearing. This motion was denied in January 2017; the

eight circuit judges ruling on the motion were split four to four, and so

the three-judge panel decision holds.

The case was the highlight of the 2017 Supreme Court season, but Congress

passed the Cloud Act in March 2018. The Supreme Court dropped the case the

following month, as moot.

The Cloud Act means that, in general, a US warrant for information must

be honored by a US provider no matter where in the world the data is

stored. However, the provider can object if the provider believes that

turning over the information would violate the privacy laws of the hosting

country. It also allows for the negotiation of international agreements

for the fast turnover of such information; these agreements are not

treaties and so are much easier to negotiate.

A big concern for Microsoft -- and other US companies -- had been that if

the DoJ had prevailed, then foreign companies would likely be increasingly

reluctant to trust US-based cloud providers -- even when the cloud storage

is physically located outside the US. This case, therefore, was central to

Microsoft's business interests.

In a related case, a Microsoft employee was charged in Brazil with failure

to turn over Skype records. In Brazil, turning over the records was

required, but at the same time in the US turning over the Brazilian records

was (and still is) forbidden.

Supreme Court cases on privacy --

Baase 4e pp 63ff / 5e p 77

1928: Olmstead v United States

The Supreme Court ruled that federal agents did not need a warrant when

they tapped Roy Olmstead's phone.

In 1934 Congress passed the Communications Act, which created the FCC and

which also banned [in Section 605] telephone wiretaps without a warrant.

Yet the law was awkwardly worded, and wiretaps by private investigators

continued.

1967: Katz

v United States

The 4th amendment does too apply to wiretaps! Furthermore, privacy may still

exist in a public area.

Katz was using a pay phone; the FBI had a microphone just outside the phone

booth. To the appellate court, the fact that the microphone did not intrude

into the phone booth was significant in finding for the FBI; the FBI's

position was that it was simply not a "search". However, the Supreme Court

reversed.

Under Katz, the doctrine of "reasonable expectation of privacy"

(REoP) replaced the doctrine of "physical intrusion".

The problem with the REoP doctrine: as

technology marches on, isn't our reasonable expectation diminished? And

does this then give the government more license to spy?

Note the first part of the quotation above: if you expose something to the

"public", it is not private. This was later formalized in the Miller

decision, next, despite the following also from the Katz decision:

Indeed, we have expressly held that the Fourth Amendment governs not

only the seizure of tangible items, but extends as well to the recording

of oral statements, overheard without any "technical trespass under . .

. local property law." Silverman v. United States, 365

U. S. 505, 365

U. S. 511. Once this much is acknowledged, and once it is

recognized that the Fourth Amendment protects people

-- and not simply "areas" -- against unreasonable searches and seizures,

it becomes clear that the reach of that Amendment cannot turn upon the

presence or absence of a physical intrusion into any given enclosure.

This second quote strongly suggests that your "papers" do not have to be

physical, or under your direct control, to be covered by the Fourth

Amendment.

Between Olmstead and Katz, there had been a gradual recognition of

increasing scope of the Fourth Amendment, hence the thought on the part of

the Katz defense team that this was worth pursuing.

Orin Kerr has a good handle on a potential way to handle REoP on a

long-term basis: the idea of what he calls "equilibrium-adjustment".

Simply put, underlying the word "reasonable" in the Fourth Amendment is

the idea that there needs to be a balance between the police and the

public. If it's too easy for the police to spy on the public, the

amendment needs to be interpreted more broadly. If it's too hard for the

police to investigate crimes, the amendment needs to be interpreted more

narrowly. Because the Fourth Amendment is about balance, even many

Originalists have accepted this approach. For example, Justice Scalia

wrote, in the Kyllo case below, tht the decision "assures preservation of

that degree of privacy against government that existed when the Fourth

Amendment was adopted". Compare that, for example, to a possible different

Originalist interpretation that only physical searches using Eighteenth

Century methods would count.

1976: US

v Miller

425 US 435

(There are at least three major Supreme Court cases involving someone named

"Miller").

Miller's incriminating bank records were subpoenaed. Miller tried to argue

that a warrant was needed. In this he lost.

The Supreme Court ruled that information we share with others (eg our bank)

is NOT private. The government can ask the bank, and get this information,

without a warrant. (However, the bank could in those days refuse.)

Justice William O Douglas was quoted earlier as saying a person could be

"defined by the checks he writes". Douglas might not have agreed with the

Miller decision, but he died in 1975.

Third-party doctrine

The Miller decision created what is now known as the third-party

doctrine: all "business records" about us are fair game for an

ordinary subpoena. On the one hand, this is a straightforward extension of

the idea in Katz that what you expose to the public is not private (though

there is room to debate just what is "public"). On the other hand, though,

Miller had tried to use the second Katz quote above in his defense, that

papers don't have to be physically under ones control, and lost.

The decision quoted from an earlier ruling

This suggests that the transaction theory (later) of

privacy is involved: both parties have significant interests in the records.

What about "business records" that are largely irrelevant to the operation

of the business? Email providers have zero involvement in

the content of the email (except for gmail?), and cellular providers have no

interest in your nearest-tower location after you have left that particular

cell. Unfortunately, the Supreme Court has never really addressed this

aspect of the Third-party Doctrine, or for that matter even spelled out a

constitutional justification for it.

Another thread in the third-party doctrine comes from informants wearing a

wire. The Supreme Court ruled in On

Lee v US that no warrant was needed for that, whereas a warrant would

be needed if the informant were not present and the wire were simply an

eavesdropping device. The argument here is that the wire simply records what

the informant -- the third party -- has heard directly.

For a good history of the third-party doctrine by Orin Kerr, see http://www.michiganlawreview.org/assets/pdfs/107/4/kerr.pdf.

We will continue with this here in the context of

email.

1979: Smith v Maryland

Reduction of REoP by the police is not SUPPOSED to diminish our

4th-amendment rights. However, in that case the Supreme Court ruled that

"pen registers" to record who you were calling did NOT violate the 4th

amendment.

Patricia McDonough had her purse stolen. She remembered the assailant's car.

Soon after, she began receiving crank calls, and recognized the car driving

down her street. A police officer saw the car, noted its license plate, and

discovered the car was registered to Michael Smith. A pen register was

placed on Smith's home line; this revealed calls to McDonough. Based on

those calls, the police got a warrant, and at that point found further

evidence. Smith argued, through his lawyers, that the pen register was a

warrantless search and that all the later evidence should be thrown out. He

lost.

http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/scripts/getcase.pl?navby=CASE&court=US&vol=442&page=735

Application of the Fourth Amendment depends

on whether the person invoking its protection can claim a "legitimate

expectation of privacy" that has been invaded by government action. This

inquiry normally embraces two questions: first, whether the individual has

exhibited an actual (subjective)

expectation of privacy; and second, whether his expectation is

one that society is prepared to recognize as "reasonable."

First, we doubt that people in general

entertain any actual expectation of privacy in the numbers they dial. All

telephone users realize that they must "convey" phone numbers to the

telephone company, since it is through telephone company switching

equipment that their calls are completed. All subscribers realize,

moreover, that the phone company has facilities for making permanent

records of the numbers they dial....

If you want to keep a number private, don't call it!

Note the crucial issue that the defendant voluntarily

shared the number with the phone company! Of course, if you want to

use a phone, you have no choice.

Justices Stewart & Brennan dissented

The telephone conversation itself must be

electronically transmitted by telephone company equipment, and may be

recorded or overheard by the use of other company equipment. Yet we have

squarely held that the user of even a public telephone is entitled "to

assume that the words he utters into the mouthpiece will not be broadcast

to the world." Katz v. United States

What do you think of this distinction? Is there a difference between sharing

your phone number with the phone company and sharing your actual

conversation with them? Is the phone number a "business record" of continued

relevance? How does the phone number (which at the time of the case would

have been used for billing) differ from a cell-tower location? After all,

even today cell-tower locations are used to determine whether you are

roaming, and thus affect your bill.

Do you think the Supreme Court might have answered differently if they had

envisioned NSA-type "pen registers" on essentially everyone in the

United States? Note that Smith was an active suspect; the police

probably could have obtained a warrant based on McDonough's tying of Smith's

car to her robbery.

The Smith case represents a further extension of the third-party doctrine to

calling records.

2001: Kyllo v United States

Thermal imaging of your house IS a 4th-amendment search! This is a very

important case in terms of how evolution in technology affects what is a

REoP

http://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/99-8508.ZS.html

Held: Where, as here, the

Government uses a device that is not in general public use, to explore

details of a private home that would previously have been unknowable

without physical intrusion, the surveillance is a Fourth Amendment

'search', and is presumptively unreasonable without a warrant.

How long into the future will this hold? Could it be that part of the issue

was that the general public was not very aware of the possibility of thermal

imaging? If thermal imaging were

to come into not only general public awareness but also general public use (eg by equipping cellphones with IR

cameras), would the situation change?

In 2016, Caterpillar (yes, the maker of the D11

Bulldozer) has now introduced a phone with an infrared camera:

http://gizmodo.com/caterpillars-new-s60-is-the-first-smartphone-with-flir-1759685817

In 1990 the Supreme Court let stand a lower-court decision that

eavesdropping on someone else's phone call made on an old-fashioned cordless

phone (remember those?) was not an invasion of privacy because no one had a

"reasonable expectation of privacy" with these devices. Many users did know

that it was easy to listen in to someone else's call simply by playing with

the channel button. See http://articles.latimes.com/1990-01-09/news/mn-155_1_cordless-phone-transmissions.

A related issue came up in the context of John and Alice Martin's 1996

taping of an embarrassing conversation involving then-Representative Newt

Gingrich, who was engaged in a frank discussion of some ethics lapses. The

Martins used a police scanner to listen in to Rep. Gingrich's "cell"

phone; the phone was likely a first-generation analog (or "AMPS") model

that was almost as easy to eavesdrop on as a cordless phone though this

did require special equipment. The Martins were eventually fined $1,000.

See also the note above about Justice Scalia's Originalist position in favor

of this decision.

Jonas Diener

(This was not a Supreme Court case.) Jonas Diener of Virginia was using

eight times the normal amount of electricity at his home. Based on that,

police obtained a warrant, believing he was running a marijuana "grow

house". They did find some marijuana, but it was unrelated to the electric

usage. Diener was not growing marijuana. The electricity use was due to a

large-scale bitcoin-mining server Diener had set up.

Diener received a six-month suspended sentence. Initially the police seized

his computer hardware and his bitcoins.

In general, once a search warrant has been executed, it is still possible to

challenge the search by making a motion to suppress evidence

obtained from the search. (Sometimes this is called a motion to quash,

though apparently that is really supposed to apply only to warrants that

have been issued but not executed.) Diener could have argued that excessive

electrical usage is not probable cause for a drug search

-- his own bitcoin-mining operation would have been Exhibit A here -- and

there is a good chance he would have prevailed.

However, justice like that is expensive. It appears Diener settled for the

suspended sentence rather than fighting the legal principles. The fact that

the government offered a completely suspended sentence suggests that they

were worried at least a little about losing the case.

2012: United States v Antoine Jones

Jones was an alleged cocaine dealer in the Washington, DC area. Police

attached a GPS tracker to his car while it was parked in the driveway. By

following him over a 30-day period, the police were able to build a strong

case against him. But Jones argued that such tracking was unreasonable

warrantless search, despite a 1983 Supreme Court ruling that allowed

wireless tracking for single trips. The Department of Justice argued that no

one has a REoP regarding his or her movements on public streets. The DoJ

also pointed to the 1983 US v Knotts case in which police had the

manufacturer attach a radio beeper to a drum of chloroform. When Knotts

purchased the drum, police used the beeper to track him to his cabin in the

woods.

In August 2010, the DC Court of Appeals agreed with Jones, and overturned

his conviction. (This decision was known as US v Maynard.)

The ninth circuit and the seventh circuit (including Illinois) had ruled

otherwise, however.

The Supreme Court ruled unanimously in January 2012 that "the Government's

attachment of the GPS device to the vehicle, and its use of that device to

monitor the vehicle's movements, constitutes a search under the Fourth

Amendment." As such, a warrant would be required.

However, by 5-4 the court also ruled

that the issue here was the government's trespass onto private property to

install the GPS tracker. That is, the court did not

rule broadly (by explicit choice!) on the question of whether sustained GPS

tracking itself violated a person's reasonable expectation of privacy.

Justice Scalia wrote the majority opinion, arguing that rules against

government trespass should coexist with the REoP approach, and that this

particular case could be decided on trespassing grounds without the need to

consider REoP (which others on the court agreed was a problematic standard).

Note that the trespass ruling makes the decision consistent with Knotts.

Jones was tried again in January 2013; in that trial, the government used

nearest-tower location data instead of GPS data. That trial ended in a hung

jury. The government prepared for yet another trial, but Jones finally

accepted a plea bargain of 15 years with credit for time served.

In US v Katzin, 2013, the Third Circuit ruled that the

police must obtain a warrant simply to monitor GPS trackers. In

this case, the device was installed before the US v Jones decision, but the

police continued to monitor the device afterwards. The Third Circuit ruling

expressly states that a warrant is required both to install a GPS tracker

and to monitor it.

The Mosaic Theory

In the DC Circuit version of the Antoine Jones case (US v Maynard), the

court developed what they called the "mosaic theory": that one individual

record might not require a warrant, but that continued use of such data

could be a different story.

[W]e hold the whole of a person's movements

over the course of a month is not actually exposed to the public because

the likelihood a stranger would observe all those movements is not just

remote, it is essentially nil. It is one thing for a passerby to observe

or even to follow someone during a single journey as he goes to the market

or returns home from work. It is another thing entirely for that stranger

to pick up the scent again the next day and the day after that, week in

and week out, dogging his prey until he has identified all the places,

people, amusements, and chores that make up that person's hitherto private

routine.

... When it comes to privacy, however, precedent suggests that the whole

may be more revealing than the parts.

What do you think of this? In many ways, this is the heart of the

NSA-surveillance issue: that the NSA took rules allowing isolated

surveillance, and applied them universally.

Here is the Volokh

Conspiracy's take on this (by Orin Kerr). Here is another, more

positive, view of the mosaic theory: www.lawfaremedia.org/article/defense-mosaic-theory.

The FBI and cellphone location

records

Records can be of nearest-tower (cell-handoff) connections, or can be GPS

records

Supposedly the Justice Department gets warrants for GPS data (nearest few

feet), but usually does not for

nearest-tower data (which positions you to within a few miles at worst, a

few hundred feet at best).

Another distinction is between realtime data (where you are now) and

"historical" data (where you were over the past month).

The federal government has tried to claim that nearest-tower data simply

amounted to "routine business records". Are they?