Computer Ethics, Fall 2010 Week 3

Corboy Law Room 523

4:15-6:45 Mondays

Fair Use

Sony v Universal

NET Act

RIAA lawsuits

Michael Eisner

DRM

Copyright law/cases

DMCA

Read: §2.1, 2.2 of Baase on privacy

Read http://cs.luc.edu/pld/ethics/garfinkel_RFID.pdf on privacy

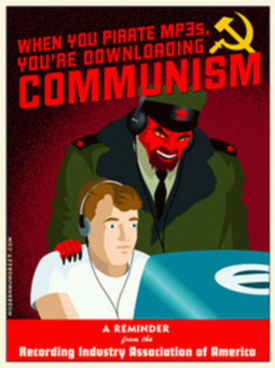

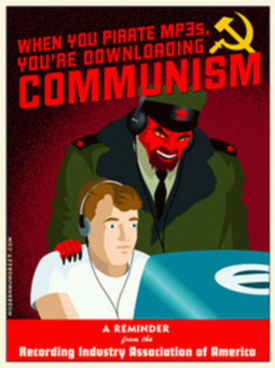

Ethical arguments about copying

Baase p 228

- I can't afford CDs

- Because I can't afford CDs and so would never buy them, Big Music

loses nothing when I download instead.

- I'm only downloading isolated tracks, not entire CDs

- It's ok to take from large, wealthy corporations. (Baase dismisses

this. Is there any underlying justification?)

- I wouldn't be buying it regardless

- I have a right to give gifts (of tracks) to my friends

- personal file-sharing is so small as to be inconsequential.

- Everyone does it.

- I'd be happy to get permission to use zzzz, but don't know where.

This is the Eyes on the Prize

problem: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eyes_on_the_Prize.

- I'm posting as a public service

- I'm posting to address some important social goal, not for sharing per se. (Legally,

this is called transformative

use)

- This is Fair Use.

What do you think of these?

Ethics of copyright: is it all about respecting the creator's right to

sell their product, that is, is it dependent on the creator's business

model?? Isn't this extremely utilitarian?

Bottom line: if we want the old rules to continue, we need to find ways

to ensure return on investment for creators of music, movies, and

books.

If.

And such ways to ensure ROI (Return On Investment, a standard B-school

acronym) can be legal, technical (eg DRM), or social.

Again, how did we get into a situation where our ethical decision making

involved analysis of ROI?

Fair Use

Legal basis for fair use

One of the rights accorded to the owner of copyright is the right

to reproduce or to authorize others to reproduce the work in copies or

phonorecords. This right is subject to certain limitations found in

sections 107 through 118 of the copyright act (title 17, U.S. Code).

One of the more important limitations is the doctrine of "fair use."

Although fair use was not mentioned in the previous copyright law, the

doctrine has developed through a substantial number of court decisions

over the years. This doctrine has been codified in section 107 of the

copyright law.

Section 107 contains a list of the various purposes for

which the reproduction of a particular work may be considered "fair,"

such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and

research. Section 107 also sets out four factors to be considered in

determining whether or not a particular use is fair:

- the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use

is of commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

- the nature of the copyrighted work;

- amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to

the

copyrighted work as a whole; and

- the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value

of

the copyrighted work.

Factor 1 relates to how you are using

the work, and is not exclusively tied to the commercial/nonprofit

issue. It may help, for example, if your use is transformative:

transforming the original work into something new and at least

partially unrelated. Factor 2 relates to the work itself: is it

fiction? Nonfiction? Text? Video? Music? A performance?

Question: does the First Amendment imply some sort of fair-use right

to quote other works?

More often, Fair Use is seen as following from the "to promote useful

knowledge"

social-contract justification under the Copyright Clause of the

Constitution.

The standard example of fair use is quotes used in a book

review. Such quotes are essential to provide an example of the author's

style, which may

be a central issue in the review. However, asking permission clearly

sacrifices the critic's impartiality.

Factor 1 is traditionally used to justify all photocopying by schools,

but this is clearly overbroad.

PARODIES are also often considered as an Item 1 fair-use exemption,

although you should be parodying the work in question and not just

using the work in a parody of something else. (Maybe not; see 1964 MAD

case below)

Here are a few parodies:

- South Park (almost any episode)

- Weird Al

- www.xkcd.com/c78.html

- Bored of the Rings

- 2 Live Crew and the Campbell

case

Generally the creator of a parody does NOT need permission of the

original author.

Factor

2 refers to whether the work is nonfiction or fiction, etc. Fundamental

news facts (and even sometimes images, eg individual frames from the

Zapruder film of the Kennedy assassination) have been ruled "fair use".

(The film itself is still under copyright, held now by the Sixth Floor

Museum.)

Sports scores are still debatable.

Factor 3: "one chapter" is probably way over the fair-use boundary.

Quoting 400 words from Gerald Ford's biography was ruled not fair use.

(However, the 400 words in question were those where Ford explained his

pardon of Nixon.)

Music sampling, in the sense of 1-2 second

snips used in another work, might

be fair use. 10-20 seconds is a

lot longer.

Factor 4: This is the big one. See Sony v Universal. A tricky problem

with Factor 4, however, is that while there might not be a market now

for the use in question, such a market could potentially develop. That

is, a market for music sampling rights might develop (has developed!)

if sampling were not claimed as fair use. A market for prerecorded

television shows has definitely developed. Later we'll consider a case

in which the plaintiff claimed that they were considering marketing

thumbnail images, and thus images.google.com's "republication" of thumbnail images was not Fair Use.

Sony v Universal City Studios, 1984

SCOTUS decision: http://www.law.cornell.edu/copyright/cases/464_US_417.htm,

by Justice Stevens.

This is the "Betamax" case, to at least some degree about fair use.

Universal Studios sued Sony for selling the betamax VCR, on the theory

that Sony was thus abetting copyright violation, and profiting from it.

District court found for Sony

Appellate court (9th circuit) found for Universal Studios

Supreme court, 5-4 decision, found for Sony

Paragraph 12 of the Supreme Court decision (emphasis added), addressing

the Four Factors of Fairness:

The District Court concluded that

noncommercial home use recording of material broadcast over the public

airwaves was a fair use

of copyrighted works and did not constitute copyright infringement. It

emphasized the fact that the material was broadcast free to the public

at large, the noncommercial character of the use, and the private

character of the activity conducted entirely within the home. Moreover,

the court found that the purpose of this use served the public interest

in increasing access to television programming, an interest that "is

consistent with the First Amendment policy of providing the fullest

possible access to information through the public airwaves. Even when

an entire copyrighted work was recorded, the District Court regarded

the copying as fair use "because there is no accompanying reduction in

the market for ‘plaintiff’s original work.‘"

Is that part about "broadcast free to the public" and the "private

character" explicit in the Four Factors? What about the part about

"serving the public interest"? Note the consideration of the effect on

the market. Note also that in 1984 there was no market for recordings

of TV shows; there is now.

The Supreme Court decision then went on to introduce the doctrine of Substantial Non-Infringing Uses,

still with us today and sometimes abbreviated SNIUs.

This case apparently legalized taping of TV programs for later viewing

(but NOT archiving). Universal did not show how it was damaged, which

didn't help their case any (presumably they thought it was obvious?).

Under the doctrine of SNIU, Substantial Non-Infringing Uses, a

distributor cannot be held liable for users' infringement (that is, for

contributory infringement) so long as the tool is capable of

substantial noninfringing uses. The precise role of "Fair Use" in the

court's reasoning is not as clear as it might be, but this certainly

DID play a role. It was actually the District Court that made that case.

SCOTUS does NOT really spell out "Fair Use" four-factor analysis,

though they hint at it in the section "Unauthorized Time-Shifting"

(paragraph 46). It was the District Court that came to the Fair Use

conclusion.

Paragraph 54: "One may search the

Copyright Act in vain for any sign that the elected representatives of

the millions of people who watch television every day have made it

unlawful to copy a program for later viewing at home"

However, there is also the following very interesting line from the

Sony decision, in paragraph 46:

Although every commercial use of copyrighted

material is presumptively an unfair exploitation of the monopoly

privilege that

belongs to the owner of the copyright, ...

This is a remarkably strong statement about commercial use! The Supreme

Court has backed away from this considerably in later decisions.

Fred Rogers testified in favor of Sony

Harry Blackmun, Thurgood Marshall, Lewis Powell, and William

Rehnquist dissented.

Criminal copyright violations

In 1994 David LaMacchia ran a "warez" site as an MIT student; that is,

he created an ftp site for the trading of (bootleg) softwarez.

He did not profit from the software downloads; in this, his site was a

precursor of today's file-sharing systems.

Because of the lack of a profit motive, the government lost its case against him. The

NET act

was passed by congress to address this in future cases. It

criminalizes some forms of noncommercial

copyright infringement, which until then hadn't

apparently been illegal. (Copyright owners like the RIAA, or in

LaMacchia's case Microsoft, could still go after you).

17 U.S.C. § 101

§ 101. Definitions

Add the following between "display" and "fixed":

The term "financial gain" includes receipt, or expectation of

receipt, of anything of value,

including the receipt of other copyrighted works.

Does this cover peer-to-peer filesharing? What if you are just

distributing music you love?

17 U.S.C. §§ 506 & 507

§ 506. Criminal

offenses

(a) Criminal

Infringement.--Any person who infringes a copyright willfully and for

purposes of commercial advantage or private financial gain shall be

punished as provided in

section 2319 of title 18. either--

- for purposes of commercial advantage or private financial

gain, or

- by the reproduction or

distribution, including by electronic means,

during any 180-day period, of 1 or more copies or phonorecords of 1 or

more copyrighted

works, which have a total retail value of more than $1,000,

shall be

punished as provided

under section 2319 of title 18. For

purposes of this subsection, evidence of reproduction or

distribution of a copyrighted work, by itself, shall not be sufficient

to establish willful

infringement.

How does the NET act affect file sharing?

Note that the law includes both reproduction and distribution.

Note the retail $1000 cutoff. Arguably that is 1,000 tracks. So far,

prosecutors have been loathe to apply the NET act to music filesharers.

This is partly due, no doubt, to the added burden of proving "willful"

infringement: the law states that file sharing itself is not sufficient

to establish "willfulness" (infringement "with knowledge of or

'reckless disregard' for the plaintiffs' copyrights" -- arstechnica.com).

In 1994, mp3 file sharing had not yet become significant.

Napster

Napster was started June 1999. Content owners promptly sued, and Napster

lost in federal district court in 2000. The Ninth

Circuit appeals court then agreed to hear the case. They granted an

injunction allowing

Napster to continue operating until the case was decided, because they

took

seriously Napster's arguments that Napster might have "substantial

non-infringing uses" and that Napster was only a kind of search engine

while

the real copyright violators were the users. The Ninth Circuit

eventually found that Napster

did indeed have Substantial Non-Infringing Uses, but they ruled against

Napster by January 2001. After some negotiating, Napster was ordered in

March 2001 to remove infringing content,

which they technologically simply could not do, and so they shut down in

July of that year.

Bottom line: the Betamax videotaping precedent [below] was rejected

because,

although SNIUs existed for Napsster, Napster had actual knowledge of

specific infringing material and failed to act to block or remove it.

Also, Napster did profit from it.

However,

the court refused to issue an injunction for quite a while; it was

clear that the Betamax precedent was being taken very seriously.

Legality in Napster era: napster.com was a clearinghouse for who was

online, and what songs they held. Actual copying was between peers.

Did that make it ok?

Napster figured the RIAA would never bother with individual lawsuits

against users.

Were they right?

Are such suits justified?

What evidence is needed for subpoena?

Note that signed and indie musicians fare VERY differently under the

napster model!

Also note the long-term implications for "future fans"

IS napster like radio?

Napsterized business model for musicians: make money giving live concerts, not selling CDs.

IS THIS REALISTIC? IS THIS FAIR? IS THIS JUST LIFE?

Is this a case of "harm" being unequal to "wrong"?

Question: is it ethical to cause harm?

What about economic harm?

RIAA Lawsuits

Part of the Napster business model was that the RIAA wouldn't ever

bother to sue individual music-file-sharers. But when file-sharing

continued after Napster was closed down, the RIAA felt forced to do

just that.

File-sharing software works by sharing your

files too; advertising

your music folder(s) online when you join the service. Investigators

look for these, by participating in online file-sharing networks. They

record your IP address and the listed songs; they also generally

download a few of the songs.

Different software works different

ways. Kazaa shows a "share" folder. bittorrent shows your connection to

a torrent "tracker" site, but there's no notion of "shared files".

Step 1: The RIAA files a "John Doe" lawsuit against your ISP.

They

issue a subpoena to your ISP, asking for your name, and, if relevant,

the MAC address of your computer. These subpoenas are almost always in

a group, asking for multiple customer names.

One legal criticism of RIAA lawsuits has been over joining together

of multiple individuals in one ISP lawsuit. Normally you can't do that

unless you believe the cases are related.

Prior to December 19, 2003, the RIAA didn't need to sue ISPs: it could

subpoena ISP records without

a lawsuit, under a provision of the DMCA. But then a court ruled that

this DMCA provision did not apply to RIAA-type cases. [RIAA v Verizon]

The ISP usually complies, usually without contacting you. However, it

is possible for either the ISP or you (if the ISP contacts you) to file

in court to "quash" the subpoena. You do need a reason for that,

however. It *is* possible to file to quash without giving up your

identity, but you have to hire a lawyer.

Step 2: the RIAA now sends you a settlement letter, offering you a

chance to settle before the lawsuit is filed. The settlement offer is

usually something like $500-1000 per track. The RIAA may or may not

distinguish between tracks that showed up in your directory, and/or

tracks that they actually downloaded.

You can refuse to settle. However, in that case the RIAA will almost

certainly go to Step 3.

Once the possibility of a

lawsuit is raised, destroying evidence becomes both a civil and criminal

offense.

Step 3: The RIAA files a lawsuit. They are likely to ask for a

forensic copy of

your hard drives (they may ask for the hard drives themselves, but

you're under no obligation to give them up). An independent forensic

examiner will copy the drive, and determine whether or not the songs

are there. (The MAC address from Step 1 plays a role here in determining

whether they've got the right computer; so does other identifying

information about KaZaa, etc.)

The cost of settlement typically goes up a little at this point.

Some defenses that have NOT helped:

- the ISP is your school, and releasing school records is illegal.

(releasing names is not

illegal)

- you didn't know it was against the law.

Yes you did. Come on.

But it doesn't matter.

- you already owned the tracks on CD.

See the Gonzalez case; www.eff.org/wp/riaa-v-people-years-later.

Copyright

law allows you to make a backup copy of what you bought; there is no

provision for receiving your backup copy from someone else.

Some possibly valid defenses in court:

The problem with all these is that you don't want to be going to court,

and the RIAA does not have to consider these when settling.

It wasn't your computer.

Typically this is due to the ISP's

misidentification of you. Sometimes it's because someone jacked your

wi-fi. In this case the forensic examination of your computer will probably help.

Your roommate used your computer

Your

problem

here is proving that this is the case. In civil cases, the

burden-of-proof requirement for the plaintiff is much more modest than

in criminal cases.

Your kids used your computer

There is a very limited legal doctrine of parental responsibility.

Originally, the RIAA did sue parents, or made them settlement offers.

More recently, after several losses, the RIAA has been suing the minors

themselves. This is a little tricky; the court must appoint an

attorney, often at the RIAA's expense. Also, in Capitol_v_Foster,

Deborah Foster eventually won $68,000 in legal fees from the RIAA.

Foster's daughter did the downloading. (The case was brought in 2004;

the RIAA dropped their suit a year later but Foster continued with her

countersuit. The judge eventually ordered the award for legal costs

without a full trial.)

You didn't actually download any songs

What the RIAA has, as

evidence, isn't evidence of downloading. All they

have is evidence that you "offered" songs for downloading. At this

point it might matter a great deal whether the RIAA actually tried

downloading anything from your computer. Jammie Thomas had her case go

to trial (the first RIAA case to reach a jury trial; Tenenbaum's July

2009 trial was the second) and she lost and was ordered to pay

$220,000. But Judge Michael Davis later rethought this issue, rejected

the "offered for distribution" theory, and ordered a new trial. Alas,

the new trial reached a judgement against Thomas of $1.9 million.

Tenenbaum case

Joel Tenenbaum was caught downloading files by the

RIAA, and was offered their past settlement offer, typically about

$5000. He chose to fight. He got Harvard Law professor Charles Nesson to

take his case pro bono; Nesson

also involved his law-school class. They put up a vigorous and spirited

defense before Judge Nancy Gertner.

They lost.

When it came time to assess damages (July 31, 2009), the jury decided

$22,500 per track was fair, for

a total of $675,000. Oops.

Actually, a core part of Tenenbaum's defense, and the central part of

his appeal, is that the damages (and settlement offer) were

disproportionately high, and not tied to actual

damages. Normally, when you sue someone, all you can ask for is actual

damages. Actual retail cost of music tracks is about $1. Tenenbaum got socked with 22,500 times actual damages!

Tenenbaum's case was the second RIAA case to go to trial. Jammie

Thomas-Rasset was first; in her first case the verdict was $222,000.

Thomas-Rasset got a new trial; the second verdict was $1,920,000.

Moral: think hard about settling early.

Tenenbaum's music downloading appeared to be both intentional

and egregious; he had actually been sharing some 800 songs.

However, it was done when he was a student.

An interesting point about the case is how the judge dismissed the

fair-use claim based on the legal theory that fair use could not apply after

Apple opened its iTunes store; that is, once it became possible to buy

individual tracks, file-sharers lost any claim to fair use. That is,

the underlying justification for "fair use" was that mp3 tracks were

otherwise unavailable. Tenenbaum's appeal in part is about the idea

that until iTunes dropped DRM its music tracks were still not really

comparable to downloaded ones.

What do you think of this Fair Use argument?

See http://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/news/2009/07/o-tenenbaum-riaa-wins-675000-or-22500-per-song.ars.

and the links at the end to earlier articles.

It's really hard to generate much sympathy for the RIAA methods.

Consider, though, the theory that file sharing is a violation of their

copyrights, and that such individual lawsuits are the ONLYway to

proceed.

What's unfair about this process? What is fixable, within the

constraints of the US legal system?

Some things to think about:

- statuary damages for infringement

- rules for defendants who

cannot afford an attorney

- rules of evidence

RIAA-2

The RIAA has officially given up on filing lawsuits against infringers,

at least for now; they announced this policy in December 2008, just

after the Tenenbaum case (lawsuits still in the pipeline will

continue). The new policy is to work with ISPs to

- notify users of infringement for the first offense

- cut off

their internet access (perhaps slowing it for a while, first)

See http://www.wired.com/epicenter/2008/12/riaa-says-it-pl.

Why would ISPs want to go along with this plan? Here are a few reasons:

- file-sharers are also huge bandwidth hogs. (Linux users are too,

but there aren't enough of us to matter. (How many times a day do you

rebuild your kernel?)) The

broadband business model basically gives every customer the ability to

download several dozen gigabytes a day, but the hope is that most

customers will actually download somewhere in the range of dozens of

megabytes a day. File-sharers who download movies pretty solidly put

themselves in the heavy-downloaders camp, tying up resources for

everyone.

- The ISP might get sued. The RIAA probably wouldn't

win, but it would be an expensive hassle.

- It's the Right Thing

To Do. Knowingly cooperating with copyright infringement is wrong.

- Eventually,

the RIAA is likely to press for laws requiring

ISPs to cooperate. Better get started now.

Bill O'Reilly on Intellectual Property (also on Privacy): http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hCSaF4KC3eE.

Bill's correspondent is attorney Megyn Kelly. Kelly acknowledges that

it is indeed a "federal offense to access email without authorization",

but goes on to say that the web site is probably ok [~2:00 minute

mark]. O'Reilly responds with "they're trafficking in stolen

merchandise" and compares it to if "you steal somebody's car".

At 3:13, he says there is "no difference between taking a person's

letter out of the mailbox and taking someones email off their internet

site".

Is there a difference?

To be fair, O'Reilly here is not talking about file sharing, but rather

someone hacking into someone (Palin's) private email account.

Michael Eisner, CEO

of Disney, testifying before Congress in June 2000: (as included in

Halbert & Ingulli, CyberEthics,

2004)

Eisner's statement remains a pretty clear example of a particular

point of view, even if some of his concerns are a bit dated. He does

use "intellectual property" as if you're just supposed to assume it's

the same as physical property. His comments about "Pirates of

Encryption" are a bit odd, especially considering that the goal of many

encryption crackers was and is the ability to play purchased DVDs on

arbitrary (eg linux) systems. Note that he appears to equate that with

credit-card theft.

[Although Eisner's remarks supposedly are from 2000, he refers to the 2003 movie Pirates of the Carribean.]

- Theft is theft. (Is this a deontological sentiment?)

-

Movies cost a lot

-

music downloading is as bad as credit card theft

-

Everyone has to play by infringement rules

-

distributing a DVD is no different from stealing newspapers

-

THEFT IS THEFT

-

[creators are entitled to] FULL RIGHTS OF OWNERSHIP

- "Today's

Internet pirates try to hide

behind some contrived New Age arguments of cyberspace"

Disney believes in technology

5 rules:

1. legislative mandate for technological fixes

2. international protection

3. public education - many don't know it is wrong

4. use appropriate technological measures

5. appropriate pricing

does free copying drive down prices?

DISCUSSION: Do you agree with Mr Eisner?

Conversly, does Disney engage in theft by overpricing (cf Eisner's 5th

rule)

Some side issues:

- What if anything was iCrave.com doing wrong? Apparently they were

simply streaming broadcast TV to the internet in real time; who loses?

They were wrapping the content in banner ads.

- How closely is file-sharing related to credit-card fraud and endangerment of children?

Can the FILM industry survive on the napster model?

Here we get into ECONOMICS. Thirty years ago, the movie industry income

from selling recordings was zero,

and the industry did fairly well. That said, it seems likely that going

back to those days would be impossible.

From 2002 to 2008, the film industry grossed more in DVD sales than at

the box office. However, that trend reversed in 2009. It is not clear

whether filesharing is a significant factor, or, for that matter, legal

on-demand downloads (which are not counted as DVD sales). (TV rights in

the past were often as large as box-office; I do not know if that trend

has continued but I doubt it.)

Figures in billions:

|

box office

|

DVD, other sales

|

rental (all forms)

|

2008

|

8.99

|

10.06

|

1.20

|

2009

|

9.87

|

8.73

|

1.27

|

Other ethics/economics questions:

- What is the FAIR amount of money to pay for something?

- Can people be EXPLOITED by receiving too low an income?

- Is HARM to other people ever justified, aside from ECONOMIC HARM?

- Are there limits to justifable ECONOMIC harm?

Check out http://thepiratebay.org.

O brave new world!

What about the market for video games that run on a general-purpose

computer, rather than a console? Supposedly the main reason this market

has all but collapsed is that it is much too easy to defeat copy

protection, and with games running $50 each, there is considerable

incentive to do this.

If this is true, it would be an example of how inability to enforce copyrights led to collapse of a market.

Console games represent, in a sense, a move by game makers to hardware-based copy protection.

(To be sure, game consoles also offer a standardized hardware platform

and guarantee high-performance graphics, but most personal computers

these days have high-performance graphics. Many of the most successful

PC-based games in fact involve registration and monthly fees (Second

Life (which can be played for free), World of Warcraft).)

Digital Restrictions Management

(aka Digital Rights Management)

How does DRM fit into the scheme here? Is it a reasonable response,

giving legitimate consumers the same level of access they had before?

Or is it the case that "only

the legitimate customers are punished"?

The general idea behind DRM is to have

- encrypted media files, with multiple possible decryption keys

- per-file,

per-user licenses, which

amount to the encrypted decryption key for a given file

- player

software (the DRM agent) that

can use some master decryption to decrypt the per-file decryption key

and then decrypt the licensed file. The

DRM agent respects the content owner's rights by not allowing the user

to

save or otherwise do anything with the decrypted stream other than play

it.

The last point is the sticky one: the software must act on behalf of

the far-away content owner, rather than on behalf of the person who

owns the hardware it is running on. Open-source DRM software is pretty

much impossible, for example; anyone could go into the source and add

code to save the decrypted stream in a DRM-free form. Windows too has

problems: anyone cat attach a debugger to the binary DRM software, and

with enough patience figure out either what the decryption key actually

is, or else insert binary code to allow saving the decrypted stream.

iPods, iPads, kindles, nooks, DVD players, and other closed

platforms are best for DRM. Under windows, DRM is one of the issues

leading Microsoft towards "secure" Palladium-style OS design under

which some processes can never have a debugger attached. ("Protected

processes" were introduced into Vista/win7.)

Most DRM platforms allow for retroactive

revocation of your license (presumably they will also refund your

money). This is creepy. Content providers can do this when your device

"phones home", when you attempt to download new content, or as part of

mandatory software upgrades.

Note that the music industry, led by iTunes, no longer focuses on DRM

sales. E-book readers, however, are still plunging ahead. One iPad

market-niche theory is that the machine will provide a good platform

for DRM-based movies and books.

Some older DRM mechanisms are based on the "per-play phone-home" model: the DRM

agent

contacts the central licensing office to verify the license. This

allows, of course, the licensing office to keep track of what you are

watching and when. This

raises a significant privacy concern. I have not heard of any recent

systems taking this approach.

Another major DRM issue is that different vendors support different

platforms. DRM might require you to purchase, and carry around with

you, several competing music players, in order to hold your entire

music library.

Perhaps the most vexing real-world DRM problem is that licenses are inevitably lost, sooner

or later. Keeping track of licenses is hard, and moving licensed

content from one iPod to the next (eg to the replacement unit) is

nontrivial. If the first iPod is lost or broken, and Apple no longer

supports the license, your content is lost. When Wal*Mart switched to

selling non-DRM music a year ago, they also dropped support for the DRM

music they'd sold in the past, meaning that those owners would see

their investment disappear whenever their current hardware platform

needed to be replaced.

Traditional CDs have a shelf life of (it is believed) a few decades,

and traditional books (at least on acid-free paper) have a shelf life

of centuries. Compare these to DRM lifetimes.

See also http://xkcd.com/488.

General copyright law rules

Different categories may be (and usually are) subject to different

rules. See http://copyright.gov/title17

for (voluminous) examples.

A local copy is at http://cs.luc.edu/pld/ethics/copyright2007.pdf.

Rules

for theatrical performances are tricky: these are ephemeral

performances! Videotaping a performance may violate actors'

rights.

Usual issue is rights of the DIRECTOR.

Copyright is held by creator unless:

- Sold

- the work is a Work For Hire

Copyright covers expression,

not content.

Famous case: Feist Publications v Rural Telephone Service:

(Feist v Rural) (1991, Justice O'Connor)

the phone book is NOT copyrightable.

(some European countries DO have "database protection". Gaak!!)

More info below

Note that if you buy a copy, you have right of private performance

(so to speak; there's no special recognition of it), but not public.

First Sale doctrine:

after YOU buy a copy, you can re-sell it. Copyright law only governs

the "first sale".

Who owns the copyright?

The creator, unless it is a "work for hire",

or the copyright is sold.

Fair Use:

This idea goes back to the constitution: the public has

some rights to copyrighted material. Limited

right of copying for reviews, etc

Good-faith defense protects schools, libraries, archives, and

public broadcasts (but not me and Joel Tenenbaum);

this limits statutory damages to $200 IF infringement was "reasonably

believed"

to be fair use. Note that, in the real world, this strategy doesn't

usually apply (though it probably means that schools don't get sued

much; it's not worth it.) Section 504(c)(2)(i).

In other cases, statutory damages may

be reduced to $200 if the "infringer was not aware and had no reason to

believe that his or her acts constituted an infringement of copyright".

Statutory damages are a flat amount you can ask for at trial

instead of

actual damages. See Section 504. Part of the theory is that by asking

for statutory damages, you do not have to prove the number of copies

made. But note the effect on the RIAA cases: actual damages might be in

the range of $1/track, if you're downloading for personal use, while

statutory damages are usually $750/track. Statutory damages were

created in an era when essentially all copyright cases that reached the

legal system involved bulk commercial copying. If a DVD street vendor

is arrested, statutory damages make sense, because of the likelihood

that a rather large number of copies have been sold in the past. But

file-sharing is about single copies.

Title 17 United States Code, Chapter 5, Section 504, Paragraph (c)

Statutory Damages. —

(1) Except as provided by clause (2) of

this subsection, the copyright owner may elect, at any time before

final judgment is rendered, to recover, instead of actual damages and

profits, an award of statutory damages for all infringements involved

in the action, with respect to any one work, for which any one

infringer is liable individually, or for which any two or more

infringers are liable jointly and severally, in a sum of not less than

$750 or more than $30,000 as the court considers just.

This was written to address large-scale commercial copyright

infringement. Should it apply to

personal use?

Laws (highlights only):

1790 copyright act: protected books and maps, for 17 years. "The earth

belongs in usufruct to the living": Thomas Jefferson

1909 copyright act: copy has to be in a form that can be seen and

read visually. Even back then this was a problem: piano rolls were the

medium of recorded music back then, and a court case established that

they were not copyrightable because they were not readable.

1972: Sound recordings were brought under Copyright.

But coverage was retroactive, and now lasts until 2067. There are NO

recordings in the public domain, unless the copyright holder has placed

them there.

1976 & 1980 copyright acts: mostly brings copyright up to date.

1976 act formally introduced the doctrine of Fair Use, previously

carved out by court cases, and formally covers television broadcasts.

1988: US signed Berne Convention, an international copyright treaty. We

held out until 1988 perhaps because Congress didn't believe in some of

its requirements [?]. 1989 Berne Convention Implementation Act: brings

US into conformance with Berne convention: most famous for no longer

requiring copyright notice on works.

[Berne Convention has since become WIPO: World Intellectual Property

Organization, a U.N. subsidiary.

WIPO: one-state-one-vote + north-south divide => rules harming

interests

of poor countries were blocked. Example: pharmaceutical patents

As a result, some international IP agreements are now under the

jurisdiction of the WTO (World Trade Organization), which the

first-world nations control more tightly.

Who has jurisdiction over IP law could be HUGELY important: the third

world is generally AGAINST tight IP law, while the first world is

generally FOR it (at least governments are)

Brief comment on treaty-based law:

A judge may work harder to find a way not to overrule a treaty,

than to find a way not to overrule an ordinary law.

1996: Communications Decency Act: not really about copyright, but it

will be important to us later.

- indecency v obscenity and the Internet

- Section 230

1997: No Electronic Theft act: David LaMacchia case (above);

criminalizes noncommercial copyright infringement if the value exceeds

$1000 and the infringement was willful.

In 1994, mp3 file sharing had not yet become significant.

1998: Digital Millenium Copyright Act passes. the two best-known and/or

most-controversial provisions:

- anticircumvention prohibition: it is illegal to help someone in

any way to circumvent copy protection

- safe-harbor / takedown

2005: recording movies in a theater is now a felony.

2009: Pro IP act

This may lead to an increase in statutory damage claims, by allowing plaintiffs to claim multiple infringements.

Some Famous Copyright Cases

Wikipedia famous copyright cases:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_leading_legal_cases_in_copyright_law.

1964: Irving Berlin et al. v. E.C. Publications, Inc.: "Mad Magazine

case"

Mad Magazine published "sung-to-the-tune-of" alternative lyrics for

popular songs.

District court ruled in MAD's favor on 23 of 25 songs.

2nd Federal Circuit decided in MAD's favor on all 25 songs.

Sony v Universal City Studios, 1984, mentioned above.

1985, Dowling v United States, 473 U.S. 207

Supreme Court

Paul Dowling ran a bootleg record company, as an Elvis fan.

SCOTUS agreed with his claim that what he did was not "theft"

in the sense of "interstate transportation of stolen property",

or fraud in the sense of "mail fraud". This was an important case in

establishing that copyright infringement was legally not the same as

theft (or, more specifically, that the illegal copies could not be

equated with "stolen property"). However, the distinction was rather

technical, addressing only whether a federal law on interstate

transport of stolen property could be applied.

From the Supreme Court decision, http://laws.findlaw.com/us/473/207.html

The language of 2314 [the

interstate-transportation-of-stolen property act] does not "plainly and

unmistakably" cover such

conduct. The phonorecords in question were not "stolen, converted or

taken by fraud" for purposes of 2314. The section's language clearly

contemplates a physical identity

between the items unlawfully obtained

and those eventually transported, and hence some prior physical taking

of the subject goods. Since the statutorily defined property

rights of

a copyright holder have a character

distinct from the possessory

interest of the owner of simple "goods, wares, [or] merchandise,"

interference with copyright does not

easily equate with theft,

conversion, or fraud. The infringer of a copyright does not assume

physical control over the copyright nor wholly deprive its owner of its

use. Infringement implicates a more complex set of property interests

than does run-of-the-mill theft, conversion, or fraud

It follows that interference with

copyright does not easily equate with theft, conversion,

or fraud. The Copyright Act even employs a separate term of art to

define one who misappropriates a copyright: ... 'Anyone who violates

any of the exclusive rights of the copyright owner ... is an infringer

of the

copyright.'

Dowling's criminal copyright-infringement conviction still stood.

Note that Dowling's case clearly met the first item of USC §506(a)(1),

namely

(A) for purposes of commercial advantage or private financial

gain;

This was the standard that the courts ruled did not apply in the David laMacchia case.

1991, Feist Publications v Rural Telephone Service

Supreme Court

(Feist v Rural) (1991, Justice O'Connor; decision: http://www.law.cornell.edu/copyright/cases/499_US_340.htm)

phone book is NOT copyrightable.

Paragraph 8:

This case concerns the interaction of

two well-established

propositions. The first is that facts are not copyrightable; the

other, that

compilations of facts generally are.

The decision then goes on to explain this apparent contradiction.

First, the essential prerequisite for copyrightability is that the

matter be original.

Some

compilations are original, perhaps in terms of selection criteria or

presentation. The phone book displays no such originality. There is

more starting at ¶ 22 (subsection B); Article 8 of the Constitution is

referenced in ¶ 23. The gist of O'Connor's opinion is that, yes,

copyright law does go back to the Constitution, and has to be

considered. In ¶ 26, she writes,

But some courts misunderstood the

statute. ..These courts ignored §

3 and § 4, focusing their attention instead on § 5 of the Act. Section

5, however,

was purely technical in nature....

What really matters is not how

you register your copyright, but whether your work is original.

In ¶27, O'Connor directly

addresses the Lockians among us: she explicitly refutes the "sweat of

the brow" doctrine.

In ¶ 32: "In enacting

the Copyright Act of 1976, Congress dropped the reference to “all the

writings

of an author” and replaced it with the phrase “original works of authorship.”"

¶ 46 states exactly what Feist did [emphasis added]. You can do it too.

There is no doubt that Feist took from the white

pages of Rural's directory a substantial amount of factual

information. At a

minimum, Feist copied the names, towns, and telephone numbers of 1,309

of Rural's

subscribers. Not all copying, however, is copyright infringement. To

establish

infringement, two elements must be proven: (1) ownership of a valid

copyright,

and (2) copying of constituent elements of the work that are original.

Bottom line, ¶ 50:

The selection, coordination, and

arrangement of

Rural's white pages do not

satisfy the minimum constitutional standards for

copyright protection. As mentioned at the outset, Rural's white pages

are entirely

typical. ... In preparing its white

pages, Rural simply takes the data provided by its subscribers and

lists it

alphabetically by surname. The end product is a garden-variety white

pages directory,

devoid of even the slightest trace of creativity.

1991: Basic Books, Inc. v. Kinko's Graphics Corporation

Federal

District Court, NY

Just because it's been published in a book does not mean you can use it freely in

teaching a course. This was considered relatively obvious; nobody

appealed.

1993: Campbell v Acuff-Rose Music, relating to the 2 Live Crew parody of

Roy Orbison's Prety Woman.

1999: Estate of Martin Luther King, Jr., Inc. v. CBS, Inc.

MLK's "I have a dream" speech is notin

the public domain. The legal issue was that the speech was delivered in

1963, before the 1989 Berne Convention Implementation Act; however, the

copyright was not registered until AFTER the speech. In the pre-Berne

era, publication before copyright could make copyright impossible. The

technical issue:

did giving the speech constitute "general" publication or "limited"

publication?

2000: UMG v MP3.com

Federal District Court, NY

The court implicitly rules that you

can't download copies even if you

already own a copy, but that might not have been the central

issue.

Copyright and traditional music

A quote from http://www.edu-cyberpg.com/Music/musiclaw2.html:

John and Alan Lomax,

who also devoted themselves to collecting and preserving traditional

folk music, took the controversial step of copyrighting in their own

names the songs they collected, as if they had written the songs

themselves. They even copyrighted original songs collected from other

singers, such as Leadbelly's "Good Night Irene."

The Leadbelly incident occurred under the pre-Berne rules, where

first-to-register meant something, even if you were registering the

copyright of someone else's work.

2006-07 Da Vinci Code case:

(actually filed in England, which has

different laws): authors Leigh & Baigent of the 1982 book Holy Blood, Holy Grail

lost their suit against Dan Brown. They had introduced the theory that

Mary Magdalene was the wife of Jesus and that Mary and Jesus have

living heirs. This was a major plot element used in Brown's 2003 book The Da Vinci Code. Did Dan Brown

violate copyright?

Not if it was a "factual" theory, which is what the judge ended up

ruling.

MGM v Grokster, 2005

Introduced doctrine of copyright inducement

Left Sony SNIU framework

intact, despite MGM's arguments against it

See http://w2.eff.org/IP/P2P/p2p_copyright_wp.php

for a lengthy article analyzing the decision.

The decision syllabus is at http://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/04-480.ZS.html,

with links to Souter's opinion.

Note that the District Court and the Ninth Circuit granted summary

judgement to Grokster!

1. Inducement:

Held: One who distributes a

device with the object of promoting its use to infringe

copyright, as shown by clear expression or other affirmative

steps taken to foster infringement, going beyond mere

distribution with knowledge of third-party action, is liable

for the resulting acts of infringement by third parties using

the device, regardless of the device’s lawful uses.

Pp. 10—24.

2. Contributory infringement.

Contributory infringement is similar to "aiding and abetting"

liability: one who knowingly contributes to another's infringement may

be held accountable. The Sony

precedent might have blocked this, but if

your primary goal is unlawful (as was Grokster's), you lose.

[continued]