Comp 353/453: Database Programming, Corboy

L08, 4:15 Mondays

Week 10, Apr 1

Problem with member---reserves---boat problem on exam:

Reserves is not actually a relationship set: the pair

(member, boat) does not determine the relationship. See the notes for Invoice

under week 6; the boat-reservation relationship is really best thought of as

ternary.

Design guidelines

Review the four guidelines from week 9.

Problem: what do we have to do to meet these guidelines?

Functional Dependencies and Normalization

A functional dependency is a kind of semantic

constraint. If X and Y are sets of attributes (column names) in a

relation, a functional dependency X⟶Y means that if two records have equal

values for X attributes, then they also have equal values for Y.

For example, if X is a set including the key

attributes, then X⟶{all attributes}.

Like key constraints, FD constraints are not based on specific sets of

records. For example, in the US, we have {zipcode}⟶{city}, but we no longer

have {zipcode}⟶{areacode}.

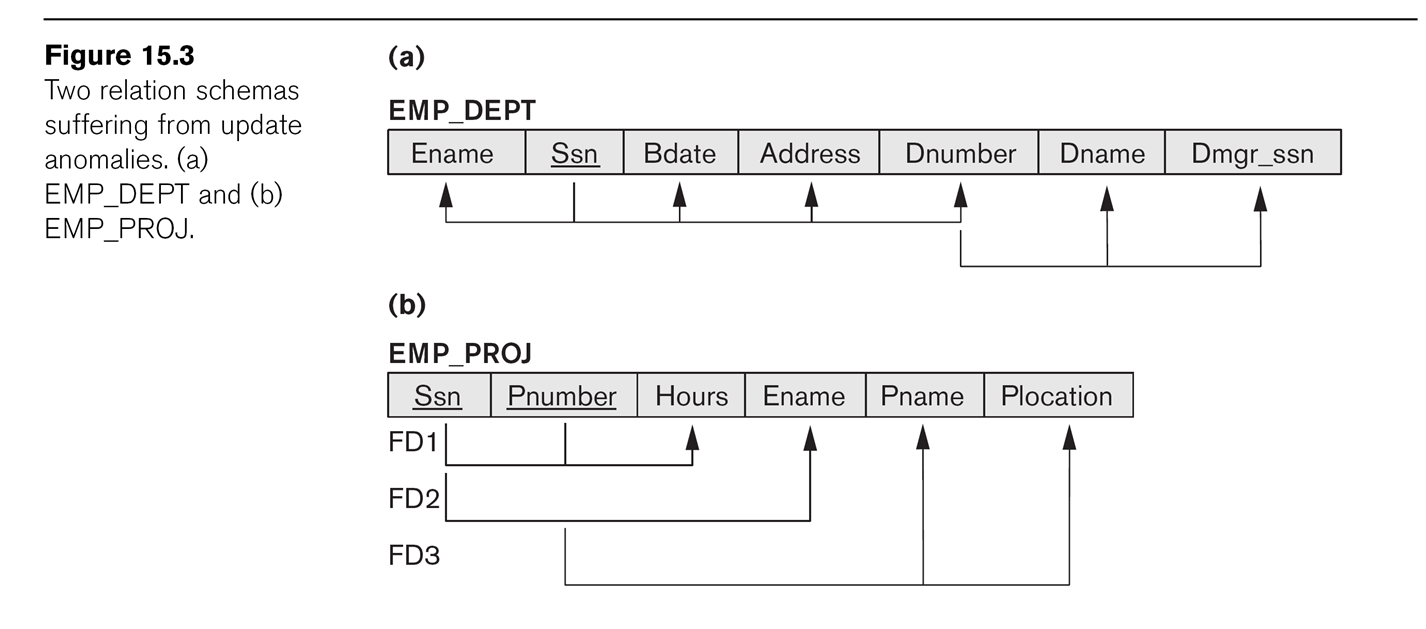

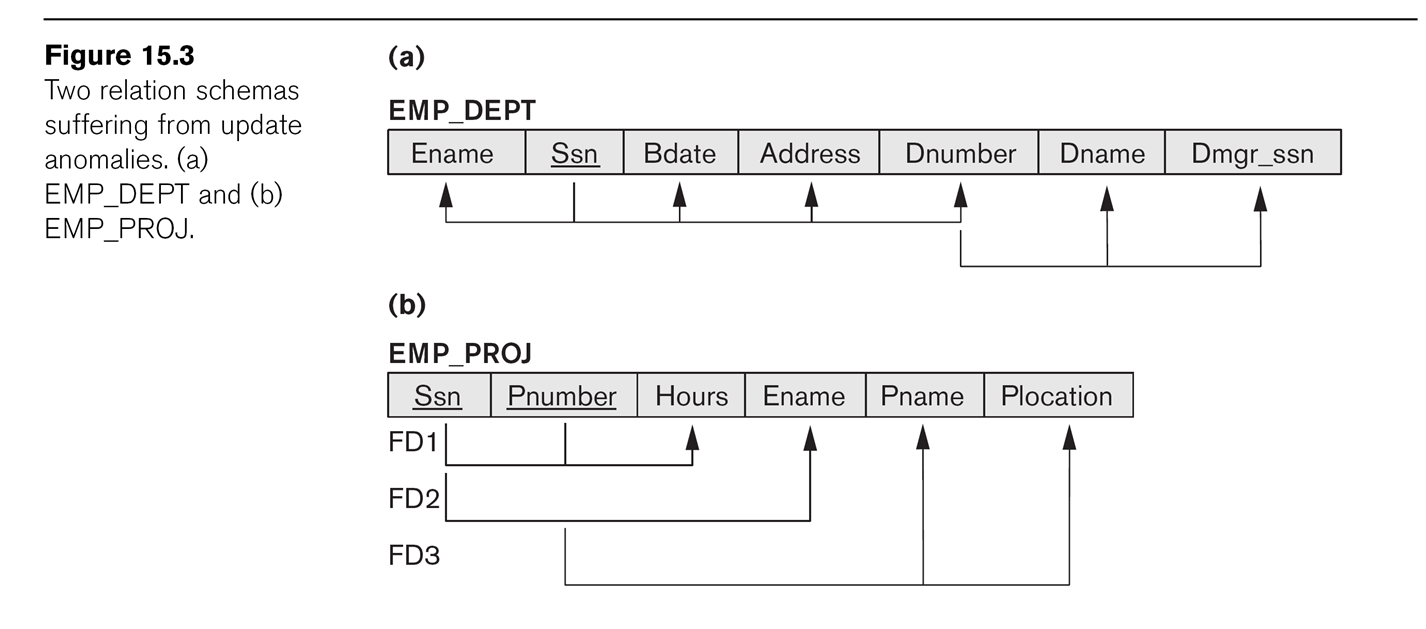

In the earlier EMP_PROJ, we have FDs

Ssn ⟶ Ename

Pnumber ⟶ Pname, Plocation

{Ssn, Pnumber} ⟶ Hours

In EMP_DEPT we have FDs

Ssn ⟶ Ename, Bdate, Address, Dnumber

Dnumber ⟶ Dname, Dmgr_ssn

Sometimes FDs are a problem, and we might think that just discreetly

removing them would be the best solution. But they often represent important

business rules; we can't really do that either. At the very least, if we

don't "normalize away" a dependency we run the risk that data can be entered

so as to make the dependency fail.

A superkey (or key

superset) of a relation schema is a set of attributes S so that no

two tuples of the relationship can have the same values on S. A key

is thus a minimal superkey: it is a

superkey with no extraneous attributes that can be removed. For example,

{Ssn, Dno} is a superkey for EMPLOYEE, but Dno doesn't matter (and in fact

contains little information); the key is {Ssn}.

Note that, as with FDs, superkeys are related to the sematics of the

relationships, not to particular data in the tables.

Relations can have multiple keys, in which case each is called a candidate

key. For example, in table DEPARTMENT, both {dnumber} and {dname}

are candidate keys. For arbitrary performance-related reasons we designated

one of these the primary key; other

candidate keys are known as secondary keys.

A prime attribute is an attribute

(ie column name) that belongs to some

candidate key. A nonprime attribute is not part of any key. For

DEPARTMENT, the prime attributes are dname and dnumber; the nonprime are

mgr_ssn and mgr_start.

A dependency X⟶A is full if the

dependency fails for every proper subset X' of X; the dependency is partial

if not, ie if there is a proper

subset X' of X such that X'⟶A.

Normal Forms and Normalization

Normal Forms are rules for well-behaved relations. Normalization is the

process of converting poorly behaved relations to better behaved ones.

First Normal Form

First Normal Form (1NF) means that a relation has no composite attributes or

multivalued attributes. Note that dealing with the multi-valued location

attribute of DEPARTMENT meant that we had to create a new table LOCATIONS.

Composite attributes were handled by making each of their components a

separate attribute.

Alternative ways for dealing with the multivalued location attribute would

be making ⟨dnumber, location⟩ the primary key, or supplying a fixed number

of location columns loc1, loc2, loc3, loc4. For the latter approach, we must

know in advance how many locations we will need; this method also introduces

NULL values.

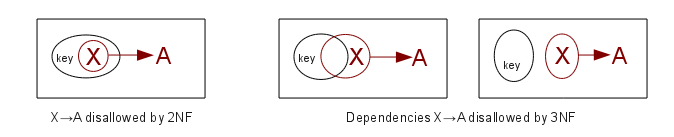

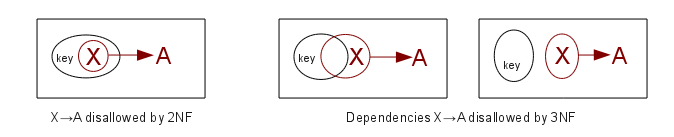

Second Normal Form

Second Normal Form (2NF) means that, if K represents the set of attributes

making up the primary key, every nonprime

attribute A (that is an attribute not a member of any key) is functionally

dependent on K (ie K⟶A), but that this fails for any proper subset of K (no

proper subset of K functionally determines A).

Note that if a relation has a single-attribute primary key, as does

EMP_DEPT, then 2NF is automatic. (Actually, the general definition of 2NF

requires this for every candidate key; a relation with a single-attribute

primary key but with some multiple-attribute other key would still have to

be checked for 2NF.)

We say that X⟶Y is a full

functional dependency if for every proper subset X' of X, X' does not

functionally determine Y. Thus, 2NF means that for every nonprime attribute

A, the dependency K⟶A is full: no

nonprime attribute depends on less than the full key.

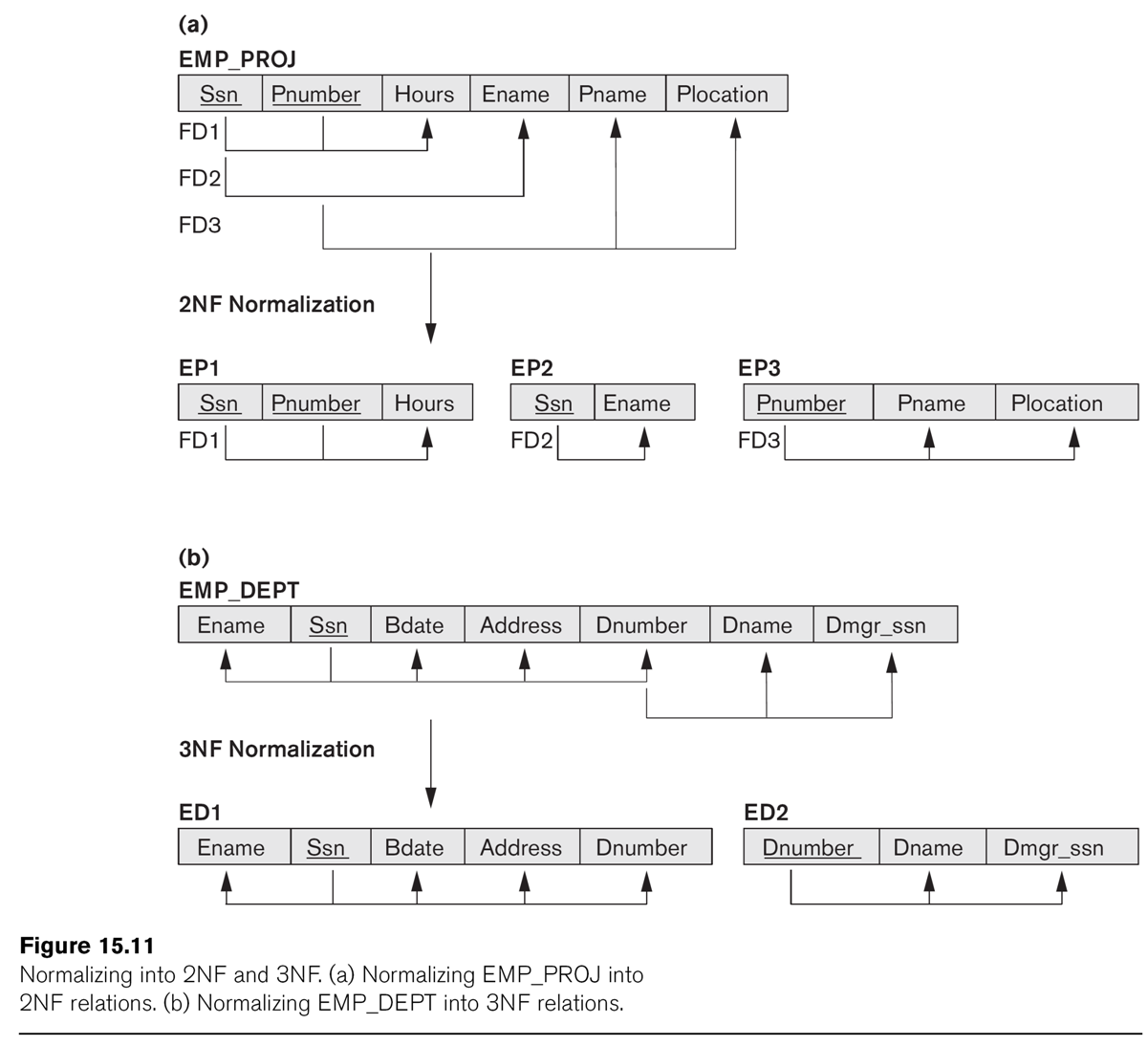

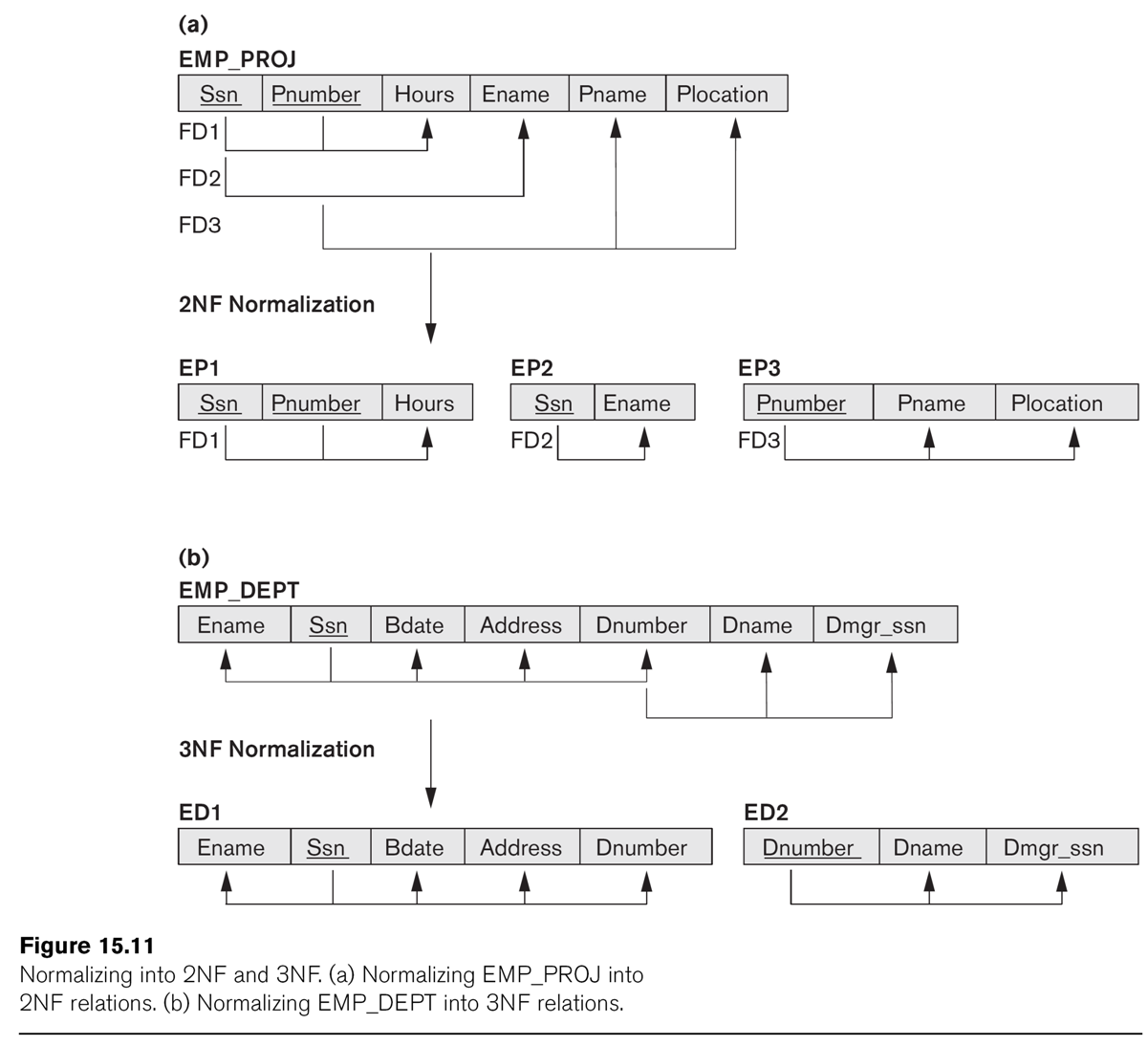

In the earlier EMP_PROJ relationship, the primary key K is {Ssn, Pnumber}.

2NF fails because {Ssn}⟶Ename, and {Pnumber}⟶Pname, {Pnumber}⟶Plocation.

To put a table in 2NF, decompose it into sets of attributes which all have a

common full dependency on some subset K' of K. For EMP_PROJ, this becomes:

⟨Ssn, Pnumber, Hours⟩

⟨Ssn, Ename⟩

⟨Pnumber, Pname, Plocation⟩

Note that Hours is the only attribute with a full FD on {Ssn,Pnumber}.

The table EMP_DEPT is in 2NF.

Note that we might have a table ⟨K1, K2, K3, A1, A2, A3⟩, where

{K1,K2,K3}⟶A1 is full

{K1,K2}⟶A2 is full (neither K1 nor K2 alone determines

A2)

{K2,K3}⟶A2 is full

{K1,K3}⟶A3 is full

{K2,K3}⟶A3 is full

The decomposition could be

⟨K1, K2, K3, A1⟩

⟨K1, K2, A2⟩

⟨K1, K3, A3⟩

or it could be

⟨K1, K2, K3, A1⟩

⟨K2, K3, A2, A3⟩

Remember, dependency constraints can be arbitrary! Dependency constraints

are often best thought of as "externally imposed rules"; they come out of

the user-input-and-requirements phase of the DB process. Trying to pretend

that there is not a dependency constraint is sometimes a bad idea.

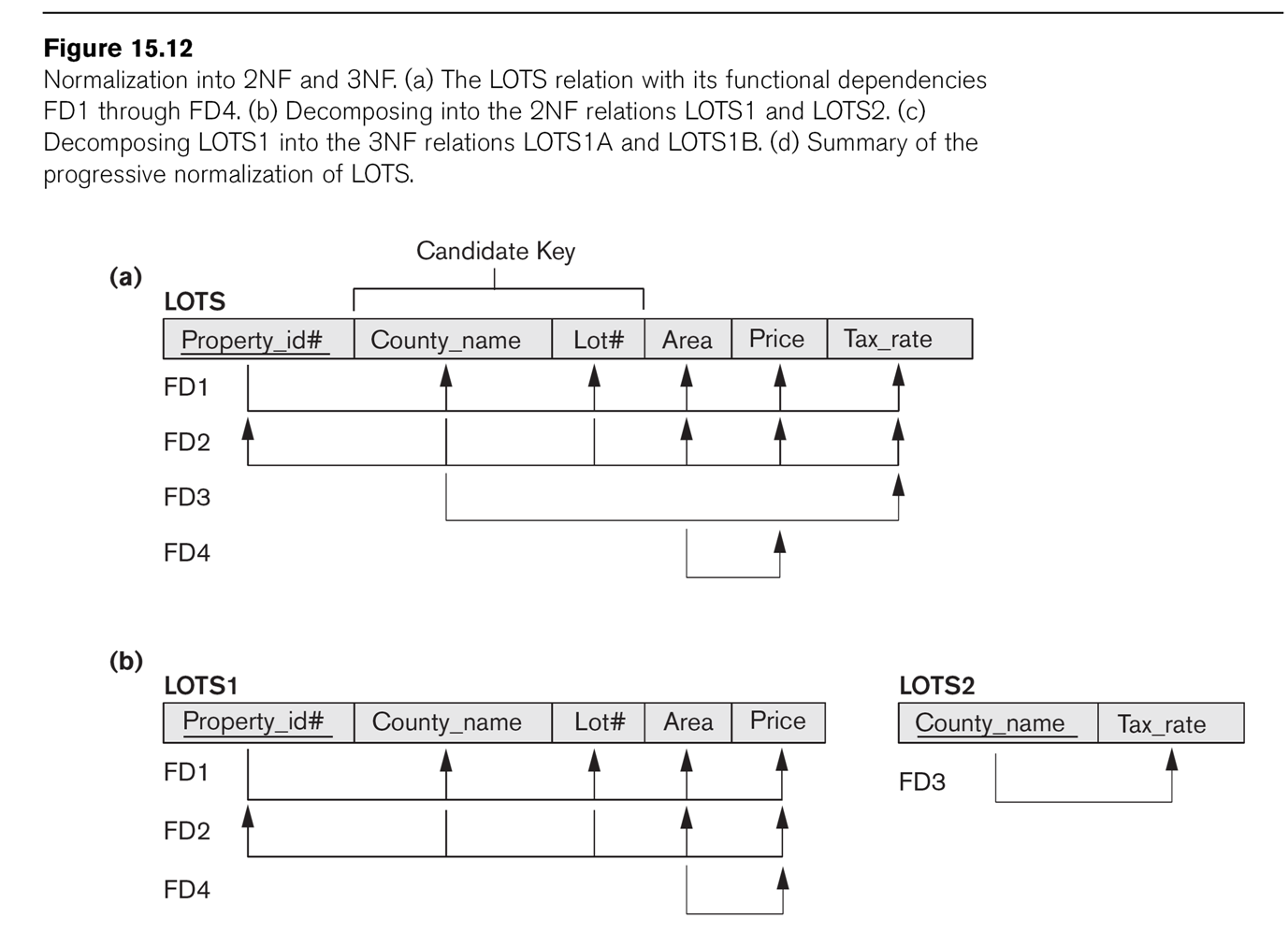

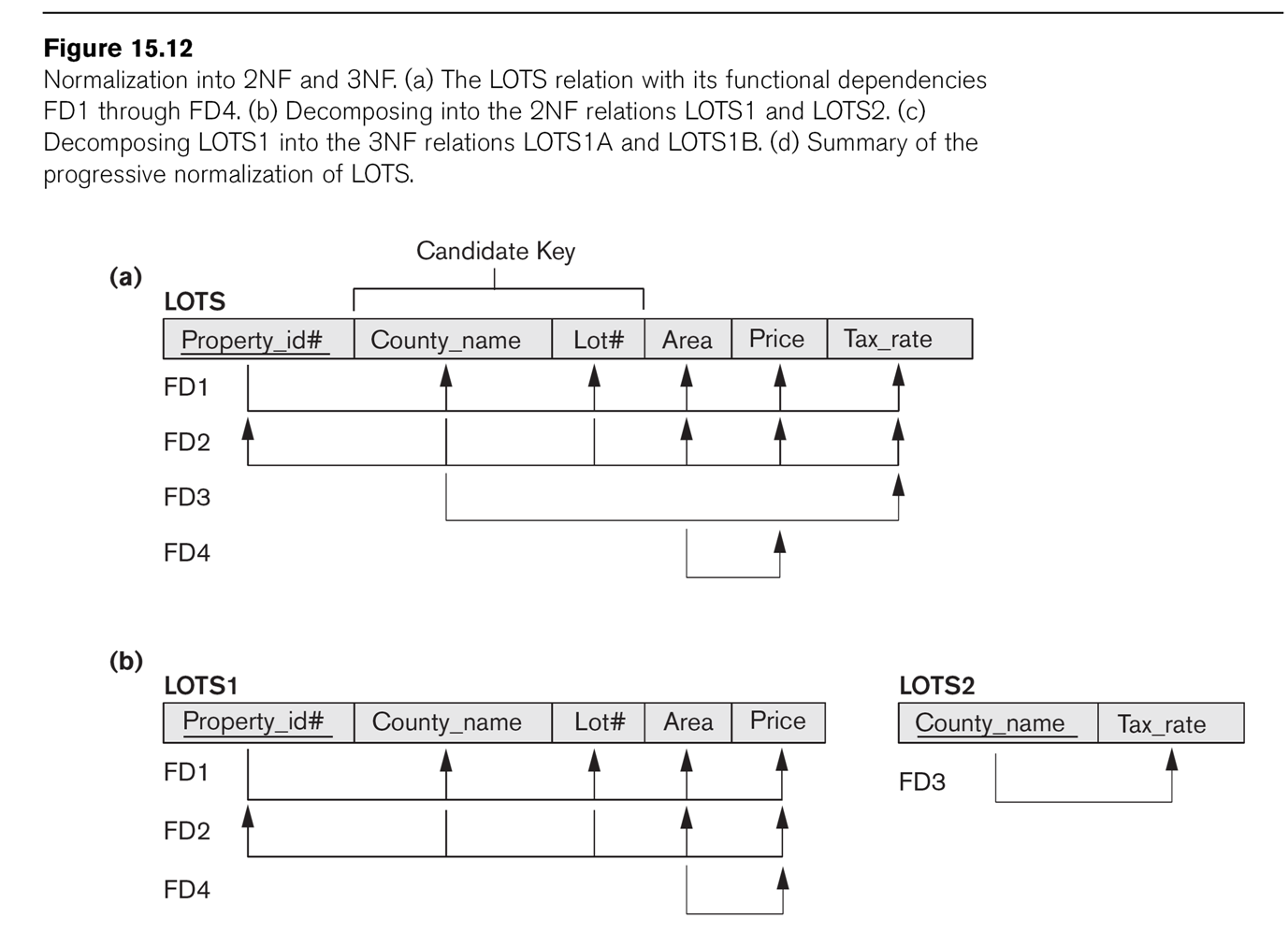

Consider the LOTS example of Fig 15.12.

Attributes for LOTS are

- property_ID

- county

- lot_num

- area

- price

- tax_rate

The primary key is property_ID, and ⟨county,lot_num⟩ is also a key. These

are functional dependencies FD1 and FD2 respectively. We also have

FD3: county ⟶ tax_rate

FD4: area ⟶ price

(For farmland, FD4 is not completely unreasonable, at least if price refers

to the price for tax purposes. In Illinois, the formula is tax_price = area

× factor_determined_by_soil_type).

2NF fails because of the dependency county ⟶ tax_rate; FD4 does not violate

2NF. E&N suggest the decomposition into LOTS1(property_ID, county,

lot_num, area, price) and LOTS2(county, tax_rate).

We can algorithmically use a 2NF-violating FD to define a decomposition into

new tables. If X⟶A is the FD, we remove A from table R, and construct a new

table with attributes those of X plus A. E&N did this above for FD3:

county ⟶ tax_rate.

Before going further, perhaps two points should be made about decomposing

too far. The first is that all the functional dependencies should still

appear in the set of decomposed tables; the second is that reassembling the

decomposed tables with the "obvious" join should give us back the original

table, that is, the join should be lossless.

A lossless join means no information is lost, not that no records

are lost; typically, if the join is not lossless then we get back all the

original records and then some.

In Fig 15.5 there was a proposed decomposition into EMP_LOCS(ename,

plocation) and EMP_PROJ1(ssn,pnumber,hours,pname,plocation). The join was

not lossless.

Third Normal Form

Third Normal Form (3NF) means that the relation is in 2NF and also there is

no dependency X⟶A for nonprime attribute A and for attribute set X that does not contain a candidate key (ie X

is not a superkey). In other words, if X⟶A holds for some nonprime A, then X

must be a superkey. (For comparison, 2NF says that if X⟶A for nonprime A,

then X cannot be a proper subset of any key, but X can still overlap with a

key or be disjoint from a key.)

2NF: If K represents the set of attributes making up the primary key,

every nonprime attribute A (that is

an attribute not a member of any key) is functionally dependent on K (ie

K⟶A), but that this fails for any proper subset of K (no proper subset of K

functionally determines A).

3NF: 2NF + there is no dependency X⟶A for nonprime attribute A and for an

attribute set X that does not contain

a key (ie X is not a superkey).

Recall that a prime attribute is an

attribute that belongs to some key.

A nonprime attribute is not part of any key. The reason for the

nonprime-attribute restriction on 3NF is that if we do have a dependency

X⟶A, the general method for improving the situation is to "factor out" A

into another table, as below. This is fine if A is a nonprime attribute, but

if A is a prime attribute then we just demolished a key for the original

table! Thus, dependencies X⟶A involving a nonprime A are easy to fix; those

involving a prime A are harder.

If X is a proper subset of a key, then we've ruled out X⟶A for nonprime A in

the 2NF step. If X is a superkey,

then X⟶A is automatic for all A. The remaining case is where X may contain

some (but not all) key attributes, and also some nonkey attributes. An

example might be a relation with attributes K1, K2, A, and B, where K1,K2 is

the key. If we have a dependency K1,A⟶B, then this violates 3NF. A

dependency A⟶B would also violate 3NF.

Either of these can be fixed by factoring

out: if X⟶A is a functional dependency, then the result of

factoring out by this dependency is to remove column A from the original

table, and to create a new table ⟨X,A⟩. For example, if the ⟨K1,

K2, A, B⟩ has dependency K1,A⟶B, we create two new tables ⟨K1,

K2, A⟩ and ⟨K1, A,

B⟩. If we were factoring out A⟶B, we would create new tables ⟨K1,

K2, A⟩ and ⟨A,B⟩.

Both the resultant tables are projections

of the original; in the second case, we also have to remove duplicates.

Note again that if A were a prime attribute, then it would be part of a key,

and factoring it out might break that key!

One question that comes up when we factor is whether it satisfies the nonadditive join property (or lossless

join property): if we join the two resultant tables on the "factor"

column, are we guaranteed that we will recover the original table exactly?

The answer is yes, provided the factoring was based on FDs as above.

Consider the decomposition of R = ⟨K1,

K2, A, B⟩ above on the dependency K1,A⟶B into R1 = ⟨K1,

K2, A⟩ and R2 = ⟨K1, A,

B⟩, and then we form the join R1⋈R2 on the columns K1,A. If ⟨k1,k2,a,b⟩ is a

record in R, then ⟨k1,k2,b⟩ is in R1 and ⟨k1,a,b⟩ is in R2 and so

⟨k1,k2,a,b⟩ is in R1⋈R2; this is the easy direction and does not require any

hypotheses about constraints.

The harder question is making sure R1⋈R2 does not contain added

records. If ⟨k1,k2,a,b⟩ is in R1⋈R2, we know that it came from ⟨k1,k2,a⟩ in

R1 and ⟨k1,a,b⟩ in R2. Each of these partial records came from the

decomposition, so there must be b' so ⟨k1,k2,a,b'⟩ is in R, and there must

be k2' so ⟨k1,k2',a,b⟩ is in R, but in the most general case we need not

have b=b' or k2=k2'. Here we use the key

constraint, though: if ⟨k1,k2,a,b⟩ is in R, and ⟨k1,k2,a,b'⟩ is in

R, and k1,k2 is the key, then b=b'. Alternatively we could have used the dependency K1,A⟶B: if this dependency

holds, then it means that if R

contains ⟨k1,k2,a,b⟩ and ⟨k1,k2,a,b'⟩, then b=b'.

This worked for either of two reasons: R1 contained the original key, and

R2's new key was the lefthand side of a functional dependency that held in

R.

In general, if we factor a relation R=⟨A,B,C⟩ into R1=⟨A,B⟩ and R2=⟨A,C⟩, by

projection, then the join R1⋈R2 on column A might be much larger

than the original R. As a simple example, consider Works_on =

⟨essn,pno,hours⟩; if we factor into ⟨essn,pno⟩ and ⟨pno,hours⟩ and then

rejoin, then essn,pno will no longer even be a key. Using two records of the

original data,

123456789

|

1

|

32.5

|

453453453

|

1

|

20

|

we see that the factored tables would contain ⟨123456789,1⟩ and ⟨1,20⟩, and

so the join would contain ⟨123456789,1,20⟩ violating the key constraint.

The relationship EMP_DEPT of EN fig 15.11 is not 3NF, because of the

dependency dnumber ⟶ dname (or dnumber ⟶ dmgr_ssn).

Can we factor this out?

The LOTS1 relation above (EN fig 15.12) is not 3NF, because of Area ⟶ Price.

So we factor on Area ⟶ Price, dividing into LOTS1A(property_ID,

county,lot_num,area) and LOTS1B(area,price). Another approach would be to

drop price entirely, if it is in fact proportional

to area, and simply treat it as a computed attribute.

4343

Multiple factoring outcomes

Consider a relation ⟨K1, K2, A, B, C⟩ where K1,K2 is the key and we have

dependencies K1⟶B and B⟶C. If we try to put into 2NF first,

by "factoring out" K1⟶B, we get tables ⟨K1,K2,A,C⟩ and ⟨K1,B⟩; the

dependency B⟶C is no longer expressible in terms of the tables. But if we

start by factoring out B⟶C, we get ⟨K1,K2,A,B⟩ and ⟨B,C⟩; we can now factor

out K1⟶B which yields relations ⟨K1,K2,A⟩, ⟨K1,B⟩ and ⟨B,C⟩; all functional

dependencies have now been transformed into key

constraints. Factoring can lose

dependencies, or, more accurately, make them no longer expressible except in

terms of the re-joined tables.

An aid to dealing with this sort of situation is to notice that in effect we

have a three-stage dependency: K1⟶B⟶C. These are often best addressed by

starting with the downstream (B⟶C) dependency.

Boyce-Codd Normal Form

BCNF requires that whenever there is a nontrivial functional dependency X⟶A,

then X is a superkey, even if A is a prime attribute. It differs from 3NF in

that 3NF requires either that X be

a superkey or that A be prime (a

member of some key). To put it another way, BCNF bans all nontrivial

nonsuperkey dependencies X⟶A; 3NF makes an exception if A is prime.

As for 3NF, we can use factoring to put a set of tables into BCNF. However,

there is now a serious problem: by factoring out a prime

attribute A, we can destroy an existing key constraint! This is undesirable.

The canonical example of a relation in 3NF but not BCNF is ⟨A,

B, C⟩ where we also have

C⟶B. Factoring as above leads to ⟨A, C⟩ and ⟨C, B⟩. We have lost the key A,B!

However, this isn't quite all it appears, because from C⟶B

we can conclude A,C⟶B, and thus that A,C is also a key, and might

be a better choice of key than A,B.

LOTS1A from above was 3NF and BCNF. But now let us suppose that DeKalb

county lots have sizes <= 1.0 acres, while Fulton county lots have sizes

>1.0 acres; this means we now have an

additional dependency FD5: area⟶county. This violates BCNF, but not

3NF as county is a prime attribute. (The second author Shamkant Navathe is

at Georgia Institute of Technology so we can assume DeKalb County is the one

in Georgia, and hence is pronounced "deKAB".)

If we fix LOTS1A as in Fig 15.13, dividing into LOTS1AX(property_ID,area,lot_num)

and

LOTS1AY(area,county), then

we lose the functional dependency FD2:

(county,lot_num)⟶property_ID.

Where has it gone? This was more than just a random FD; it was a candidate key for LOTS1A.

All databases enforce primary-key constraints. One could use a CHECK

statement to enforce the lost FD2 statement, but this is often a lost cause.

CHECK (not exists (select ay.county,

ax.lot_num, ax.property_ID, ax2.property_ID

from LOTS1AX ax, LOTS1AX ax2, LOTS1AY ay

where ax.area = ay.area and ax2.area = ay.area

// join condition

and ax.lot_num = ax2.lot_num

and ax.property_ID <> ax2.property_ID))

We might be better off ignoring FD5 here, and just allowing for the

possibility that area does not determine county, or determines it only "by

accident".

Generally, it is good practice to normalize to 3NF, but it is often not

possible to achieve BCNF. Sometimes, in fact, 3NF is too inefficient, and we

re-consolidate for the sake of efficiency two tables factored apart in the

3NF process.

Fourth Normal Form

Suppose we have tables ⟨X,Y⟩ and ⟨X,Z⟩. If we join on X, we get ⟨X,Y,Z⟩. Now

choose a particular value of x, say x0, and consider all tuples ⟨x0,y,z⟩. If

we just look at the y,z part, we get a cross

product Y0×Z0, where Y0={y in Y | ⟨x0,y⟩ is in ⟨X,Y⟩} and

Z0={z in Z | ⟨x0,z⟩ is in ⟨X,Z⟩}. As an example, consider tables

EMP_DEPENDENTS = ⟨ename,depname⟩ and EMP_PROJECTS = ⟨ename,projname⟩:

EMP_DEPENDENTS

ename

|

depname

|

Smith

|

John

|

Smith

|

Anna

|

EMP_PROJECTS

ename

|

projname

|

Smith

|

projX

|

Smith

|

projY

|

Joining gives

ename

|

depname

|

projname

|

Smith

|

John

|

X

|

Smith

|

John

|

Y

|

Smith

|

Anna

|

X

|

Smith

|

Anna

|

Y

|

Fourth normal form attempts to recognize this in reverse, and undo it. The

point is that we have a table ⟨X,Y,Z⟩ (where X, Y, or Z may be a set

of attributes), and it turns out to be possible to decompose it into ⟨X,Y⟩

and ⟨X,Z⟩ so the join is lossless.

Furthermore, neither Y nor Z depend on X, as was the case with our 3NF/BCNF

decompositions.

Specifically, for the "cross product phenomenon" above to occur, we need to

know that if t1 = ⟨x,y1,z1⟩ and t2 = ⟨x,y2,z2⟩ are in ⟨X,Y,Z⟩, then so are

t3 = ⟨x,y1,z2⟩ and t4 = ⟨x,y2,z1⟩. (Note that this is the same condition as

in E&N, 15.6.1, p 533, but stated differently.)

If this is the case, then X is said to multidetermine

Y (and Z). More to the point, it means that if we decompose into ⟨X,Y⟩ and

⟨X,Z⟩ then the join will be lossless.

Are you really supposed even to look

for things like this? Probably not.

Fifth Normal Form

5NF is basically about noticing any other kind of lossless-join

decomposition, and decomposing. But noticing such examples is not easy.

16.4 and the problems of NULLs

"There is no fully satisfactory relational

design theory as yet that includes NULL values"

[When joining], "particular care must be

devoted to watching for potential NULL values in foreign keys"

Unless you have a clear reason for doing otherwise, don't let foreign-key

columns be NULL. Of course, we did just that in the EMPLOYEE table: we let

dno be null to allow for employees not yet assigned to a department. An

alternative would be to create a fictional department "unassigned", with

department number 0. However, we then have to assign Department 0 a manager,

and it has to be a real manager in

the EMPLOYEE table.